interviews the curators of the Getty Museum’s Hiroshi Hamaya and Kansuke Yamamoto Photo Exhibit

The history of Japanese photography underwent a significant change in the 1930s. The traditional pictorial-influenced movement merged into New Photography (Shinko Shashin), which was particularly inspired by concepts from the German New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit). Fueled by technical advances, the movement evolved into two opposing directions: one toward documentary photography and photojournalism which focused on social realism and the other pursuing experimental avant-garde practices that were strongly influenced by Western Surrealism.

Born during the Taisho era (1912-1926), photographers Hiroshi Hamaya (1915–1999) and Kansuke Yamamoto (1914–1987) took starkly opposite directions in regards to photographic approach and style. While Hamaya took a photojournalistic approach to document regional subjects and social issues, Yamamoto adopted experimental, avant-garde techniques to create innovative photographs, collages and poems strongly influenced by European Surrealism.

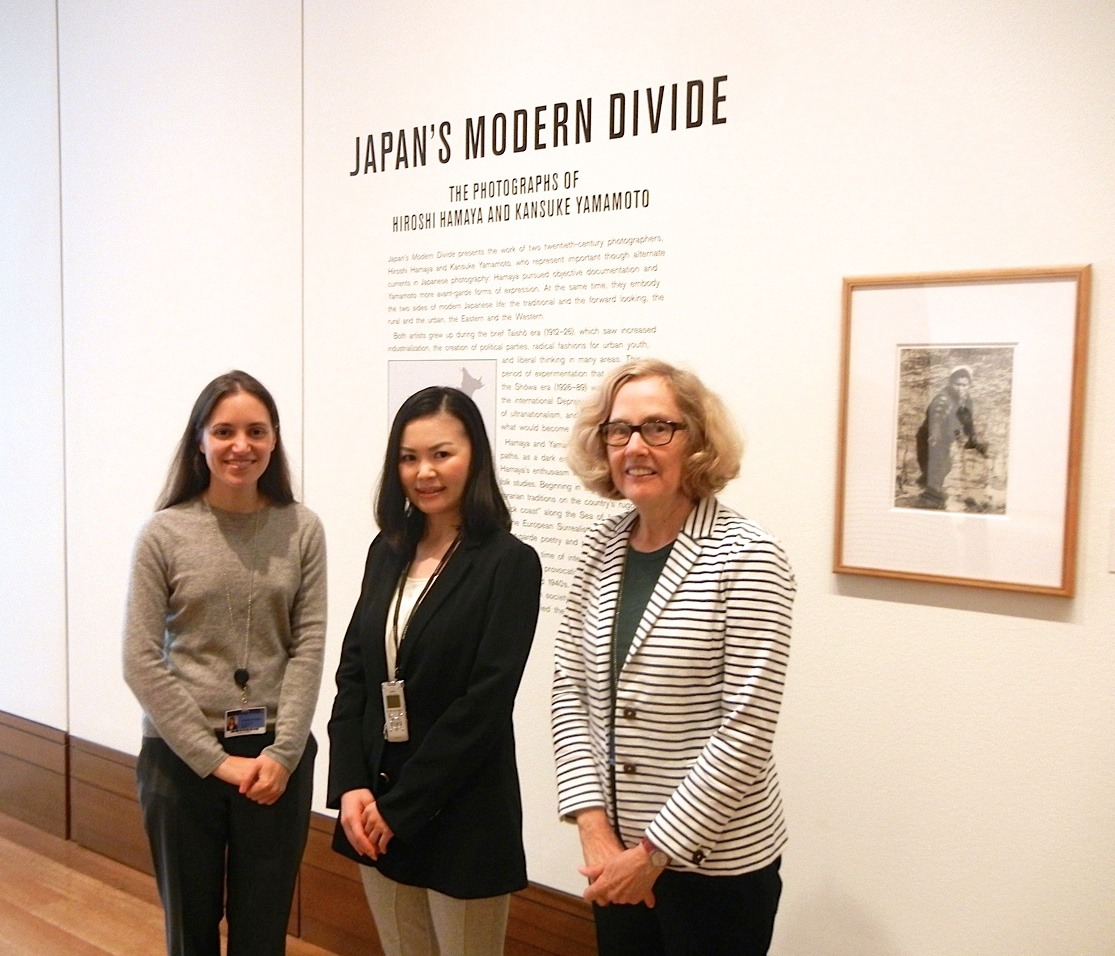

The J. Paul Getty Museum’s recent exhibition “Japan’s Modern Divide: The Photographs of Hiroshi Hamaya and Kansuke Yamamoto” (March 26-August 25, 2013) featured the extraordinary work of two photographers who represent distinct trends among the dramatic transformations of the era. Japanese would probably not come up with the idea of putting these two photographers together, because curators in Japan tend to define artists and their works strictly within genre constraints. A parallel exhibit from a Japanese museum’s side might be to pair Hungarian-born, American photojournalist Robert Capa and American Surrealist Man Ray.

Nevertheless, the result of placing the two photographers in their parallel chronological contexts was a resounding success for the American audience. By reframing the history of mid-20th century Japanese photography through Hamaya’s documentary style and Yamamoto’s Surrealist take, the show shed light on the unique features and development of Japanese photography. The exhibit also provided a fresh perspective on the complexities of Japanese modern life bridging prewar, war, and postwar times: the traditional and the modern, the rural and the urban, the oriental and the occidental.

The curators have achieved not only the presenting of a chronological overview of the photographers’ careers, but also an examination of how their styles and themes developed as they diverged over time, and how they pushed the boundaries in their creative pursuits by continuously seeking new photographic challenges within their respective approaches.

Hiroshi Hamaya was born and raised in Tokyo, the son of a detective. After making aerial images for an aeronautical institute, he embraced photojournalism and became a freelance photographer. In 1939, he became interested in documenting traditional regional folklore and rituals that were on the brink of disappearing due to modernization. He chose Japan’s west coast as a photographic destination and recorded the daily lives and seasonal rituals of farmers and fishermen over the next two decades. In 1960, he became the first Asian photographer to join the international photographic cooperative Magnum Photos. After covering the demonstration against renewing the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty in 1960, he once again turned his attention to aerial photography and recorded stunning vistas of nature in several global localities. His career embraced ethnographic studies documenting rituals, portraiture of artists, protest demonstrations, and nature without human interference.

Kansuke Yamamoto was born in Nagoya, and his father owned a photo supply shop and studio. Yamamoto developed an interest in both photography and poetry as a teenager. From the beginning of his career, Yamamoto drew artistic inspiration from Surrealism, experimented with various photographic techniques including collage and montage, as well as three-dimensional forms and paintings. By the late 1930s, however, Japanese society was radically altered due to Japan’s acceleration of militarization. With avant-garde and Surrealist art often deemed subversive by the Thought Police (tokko), Yamamoto came under fire and was interrogated around 1939. As a result he was forced to cease publication of his art journal Yoru no Funsui (Night’s Fountain, 1938-39). The experience made a profound impact on him, but never deterred his rebellious spirit. Yamamoto’s images are starkly original and sophisticated, but embedded within his aesthetically refined and often mysterious works is sharp social commentary. With his non-conformist attitude and indomitable spirit, he continued his photographic and poetic experimentation throughout his lifetime.

The Getty Museum’s outstanding international reputation for staging top quality photographic exhibitions is well attested to, yet it came as a surprise that this show met with such undisputed acclaim. This is especially true when considering that Hiroshi Hamaya is not as well known as the highly popular generation of Japanese photographers who followed him, such as Eikoh Hosoe, Daido Moriyama and Hiroshi Sugimoto. As for Yamamoto, he must be one of the greatest unknown artists in Japan, and his work has been lingering in relative neglect for decades.

Within the first four months of its run, the Getty Museum exhibit “Japan’s Modern Divide” attracted more than 200,000 people (after five months, 360,000 had visited). Back in 2001, when the solo show “YAMAMOTO Kansuke: Conveyor of the Impossible” was held at Tokyo Station Gallery, the exhibit was viewed by 9,000 visitors. The Getty’s exhibit―seen by 20 times more people than the Japanese exhibit―is undoubtedly a huge step towards international mainstream recognition for Yamamoto Kansuke’s work, ironically with the Japanese photographic establishment limping behind.

The exhibition was curated by Judith Keller, senior curator of photographs, and Amanda Maddox, assistant curator of photographs, both at the Getty Museum. The catalogue edited by them, Japan’s Modern Divide, was published by the Getty Museum. The author interviewed the curators in the exhibition galleries on June 11, 2013 and wishes to express her gratitude for their time, enthusiasm and frank answers.

Is this the first major exhibit of Hamaya Hiroshi and Yamamoto Kansuke outside Japan?

JK: Yes, it certainly is the only exhibit of Hamaya and Yamamoto anywhere ever. There has never been another exhibition that paired the two of them, but in terms of their work being shown individually outside Japan, Hamaya had solo exhibitions in New York twice, in 1968-69 and in 1986 at the ICP [International Center of Photography] in New York.

AM: Yamamoto Kansuke has not been shown very much at all outside of Japan, and I think that even in Japan, despite contributing to many exhibits during his lifetime, it wasn’t until the 2001 Tokyo Station Gallery exhibit that people really became familiar with his work. Yamamoto’s work and career are not well known in the United States although his work was included in the “The History of Japanese Photography” exhibition [2003] that was organized by the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, and recently there was the “Drawing Surrealism” exhibit at LACMA [2012] in which an image of his was shown. This is the first exhibition that shows a wide range of Yamamoto’s work and covers his entire career.

I heard the Yamamoto/Hamaya show has attracted a large number of visitors. Why does the show attract so many people?

JK: Well, I think it is partly a matter of it being photography. Our photography shows here at the Getty regularly attract a very large audience. I think between the reputation of the photography department here at the Getty and I hope the quality of our photography shows as well as it being an unusual show in that it consists of two people who we feel are very important to the history of Japanese photography. It is presenting not quite a retrospective of each of them but more of an in-depth view of each of them than has ever been shown anywhere. And this is different from surveys of Japanese photography—not that there have been that many of them—but the only recent one was the 2001 Houston show. That was a very large survey of the history of Japanese photography, which included both of these photographers in the form of a few pictures. And then there have been a couple of solo shows for the most prominent contemporary Japanese photographers like Moriyama [Daido] and Tomatsu [Shomei]. But what we’re doing is presenting two people—Hamaya Hiroshi and Yamamoto Kansuke—who we feel were cornerstones of 20th century Japanese photography and because of their key role in both the documentary and experimental, avant-garde work, they should both be better known. I hope people are coming for that reason. And also because I think that the show presents Japanese history in a way that the changes in the culture over the 20th century, and a lot of people in Los Angeles, which is a huge population, are interested in that. So it’s a combination of photography and Hamaya and Yamamoto.

John Solt[1] wrote in the Tokyo Station Gallery catalog of 2001 that the Japanese media has been “asleep at the wheel” in not noticing Yamamoto adequately. What has been the Japanese media’s reaction to this exhibition so far? I saw it was in the Japanese edition of Vogue magazine mentioned with other current Japanese exhibitions in the US.

JK: Well, I hope that there has been more attention given to it in the Japanese media than we’re aware of. There was one article.

AM: There was one person who came from UTB and did an interview with Yamamoto Toshio, but there haven’t been too many inquiries. Nothing has reached us yet. [Note: The interview begins 4:18 into the video.]

Have you gotten any direct feedback from the visitors to the exhibition?

JK: Some, especially people whom we know such as those from our photographic arts council [PAC] who have been very pleased. I guess the main feedback was during the nice opening, and people did look very closely at the work and a lot of them just seemed amazed by the quality of the work as well as the fact that it was happening here in Los Angeles.

AM: And some other curators were in town for Paris Photo Los Angeles,[2] and were able to come and see it. I think for most people it is new material, because it hasn’t been presented together as a combination of two artists or in this depth for either artist. I think people were really happy to see this much work by both of these artists.

JK: We were especially happy that Anne Tucker,[3] who organized the 2001 exhibit in Houston, was able to see it. She had to come to Los Angeles for another exhibit—she was the curator of the War Photography Exhibit that going on at the Annenberg Space for Photography. Anne organized that show and was in Los Angeles for events around that show, and she came [to the Getty] and was very happy that other museums were following up on her lead of bringing attention generally to the field [of Japanese photography].

Iizawa Kotaro (the photography historian, critic and curator based in Tokyo) wrote in the exhibit catalog that Hamaya and Yamamoto are like “oil and water.” Their photographic approaches and styles are completely different and we Japanese would probably not come up with the idea of putting the two of them together. What gave you the idea to combine them, and what was the rational behind it?

AM: I would point out that while they were stylistically very different, they were living at the same time period throughout the 20th century in Japan. They also began their careers in similar ways—they were both interested in experimental photography at the beginning, but Hamaya chose to go in a different direction. So I think it is important for people to understand that at least at the outset they weren’t very different. It was in the 1930s and 1940s when they were beginning to form their careers that their paths went in separate directions.

JK: And that is something we tried to make clear in the show. It could give people a false impression—because we’re just presenting two photographers—that there weren’t movements around both of these types of photography. We introduce them as representatives, as examples, of these two very different veins in mid-20th century Japanese photography. We feel that they are exceptional representatives of these two veins, and the exhibit had a lot to do with the fact that the keepers of the work of these two artists—they as well as their heirs (the people who now take care of their estates)—had protected the work and had saved it, basically, and yet were willing to make it available to the museum. And that is a very important aspect as well. These are important people and their work is available. It seemed to us harder in Japan than in the US or Europe to find the material, to find examples of their work from the 1940s and 50s and 60s. Work that they made themselves at the time of the negatives, or their experiments, and it still survives in very good condition for the most part. And the people who cared for it were very cooperative. We couldn’t have done it without the very generous cooperation of the heirs and executors of the estates. In planning a show that would present some of the most important things going on in Japanese photography in the 20th century, these other things had to come together. We had to learn what was available and find out who was willing to share it with us.

Has it been challenging to exhibit two photographers whose reputations have not yet been firmly established in the West (and in the case of Yamamoto, even in Japan)?

JK: Amanda may have a different take on this, but the most challenging part for us was the language. Neither of us are experts in the language. We are not John Solts. We are not experts in the history of Japanese avant-garde art. We know the West and what has gone on there and the histories written. I would say that the challenging part was the language and not being able to read Japanese, for which we had to hire translators.

AM: Most of our material was in Japanese, especially for Yamamoto. John Solt is one of the only people who has written anything in English about him. There is really not very much written about Yamamoto specifically or, even more broadly, about Japanese avant-garde photography or Surrealist photography. Two particularly good books on the topic are in French—Dada et Surrealisme au Japon and Japon des Avant Gardes, 1910-1970—so some text was essentially translated from Japanese to French to English. It was definitely a challenge to find all the research materials that we needed, but the estates were very cooperative. Yamamoto Toshio,[4] for example, would send us diary entries from his father’s diaries that we were able to incorporate into the text in the essays. And John Solt had translated poems, so we had material to draw from.

JK: It was a combination of talking to the heirs—the caretakers of the art—because they of course were people who knew the artists. Mr. Tsuguo Tada,[5] who is directing the Hamaya estate, was very helpful to me early on, even though there was something of a language barrier in our discussions. He is a very good researcher himself, and he was always happy to answer my specific questions about Hamaya’s history. It was more challenging than our normal projects but certainly worth it.

Could you explain how you interpret the title that you gave to the exhibition, namely “Japan’s Modern Divide”?

AM: The two artists not being well known in the US caused us to think a lot about the title of the exhibition, with the understanding that there wasn’t a name recognition in the US for Hamaya Hiroshi or for Yamamoto Kansuke. Therefore, it was important to make sure that Japan and Japanese photography came through in the title of the exhibition.

JK: Amanda came up with the title. That was another of the big challenges to try to represent not just the fact that there were two very different photographers in the exhibition, but that they represented two very different directions in the thinking of people in Japan in the mid-20th century. Because so much modernization had taken place, and then the very conservative, militarist government came into power and was trying to turn the country in the other direction soon after immense development had taken place. There was an intense debate about whether modernization was good or bad and how much it was corrupting the Japanese traditions and unique practices. We wanted to get that all in, and that’s a lot to try to get from a title. Also, they like for us to have very short titles here for advertising and marketing purposes. “Japan’s Modern Divide” fit the bill.

Which photo of Hamaya and Yamamoto first attracted you? Can you explain how you remember the encounter?

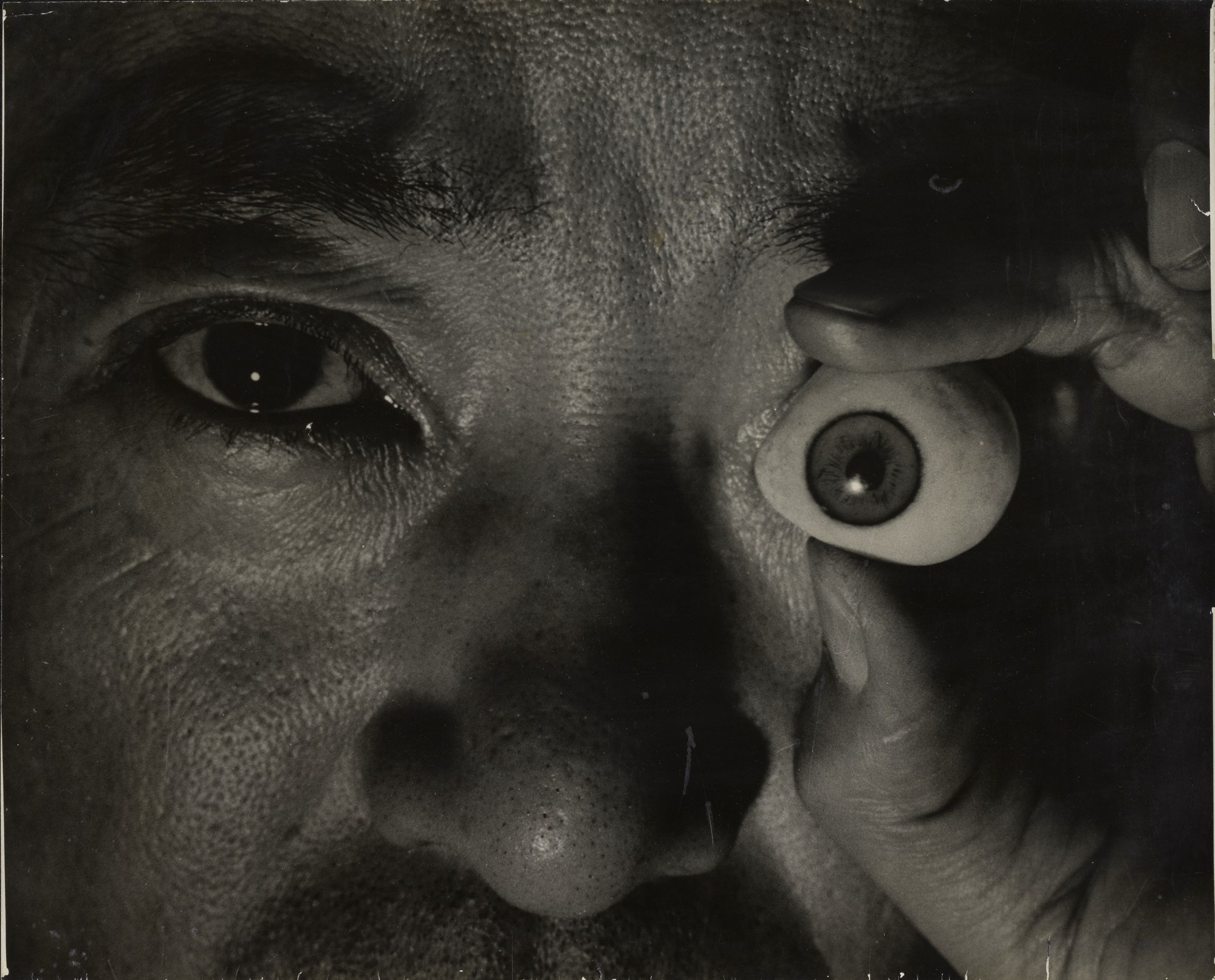

AM: When I came to the Getty, the show was already in process and I was not familiar with Yamamoto’s work. But I think that for me it was the image of the eye [Yamamoto’s self-portrait holding an artificial eye over his left eye] which we saw in Japan in October 2011 when researching Yamamoto and Hamaya. This image revealed so much in terms of Yamamoto’s understanding of Surrealism, and his sense of playfulness. Relatively speaking, it is a larger print, so you could understand his technical aptitude as a photographer. And it’s hard not to be confronted by him, because he’s staring right back at you. I think that was the one that stood out initially amongst the group when we were first looking through the prints as something that was pretty powerful.

JK: I think the first image I saw by Hamaya was the only one of his images that has been widely reproduced, which is of the woman planting rice whose head he has cropped out. So you see only the torso, and she is knee deep in the mud. But once I started looking at more than one photograph and was meeting with Mr. Tada, I encountered other important images like the one of the person in the bamboo raincoat which is practically as large as the figure and has some writing on it which is the name of a commercial company. It is nearly abstract, although there is landscape in the background. What has interested the photographer is not only the type of raincoat and the person who is wearing it, but the shape of the raincoat and how it makes the figure into something else. And as John Solt pointed out in his talk [at the Getty] last week,[6] some of Hamaya’s images can be seen as surrealistic as Yamamoto’s work. His motivation was documentary, but he clearly had the eye of an artist.

I think it’s courageous of you that Front, the WWII propaganda photo magazine [1942-45] is on display at the entrance of the exhibit.

JK: Well, it’s there because Hamaya did work for Front for at least a year and a half before he quit because he was upset about the way that his images were being used for propaganda. Front is a very important journal not just as an example of propaganda, but as an example of graphic layout and graphic art. It’s really amazingly done, and was influenced by what was going on in the Soviet Union and Constructivist design. Art from other parts of Europe had a big impact on it and some of the best photographers and designers were working for it. It has several meanings in terms of Hamaya’s background, and I think he learned a lot, even though in the end he wasn’t happy about the way things worked there. He did probably absorb things that were important to his own work, especially with books in the future. He was the one who laid out the books that he started publishing in the 1950s.

I don’t know if “courageous” is apt, but Front is part of his history and part of Japan’s history and the history of graphic design and photography. It should be there. I’m sorry that we couldn’t show more.

AM: And it was also during the time that Hamaya was working for Front that he was first sent on assignment to the back coast of Japan. That period when he was working for Tohosha [the publisher of Front] was for him a very important time in terms of what came after and his whole experience of working up and down the coast.

JK: Yes, it was the armed forces who sent him first to Niigata, to the back coast, and to Takada, where the ski corps was conducting exercises. That’s where his interest in the back coast started.

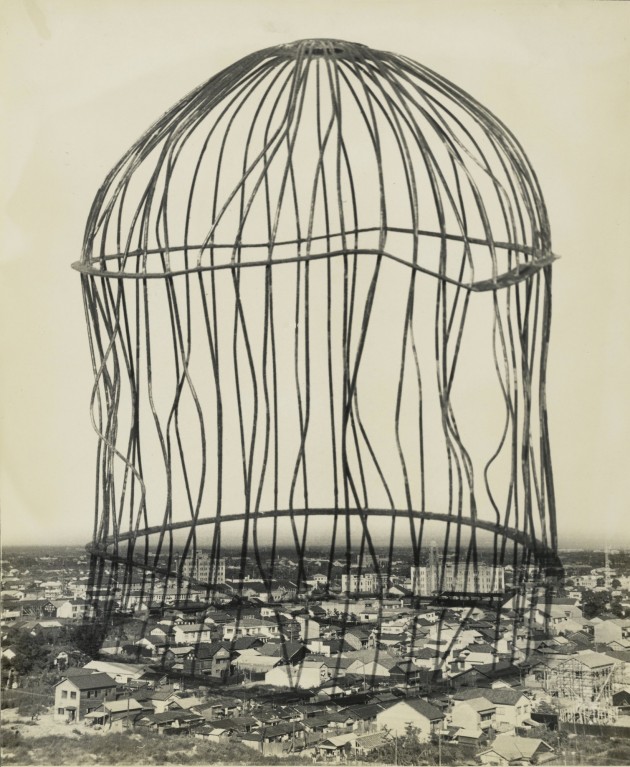

Yamamoto’s “Reminiscence” (a bird cage and landscape of a devastated city) is used for the cover of the exhibit catalog. The photo implies a memory of devastation, an atomic bomb kind of landscape. I think that was also a courageous choice for the cover of your catalog. Why did you select it?

AM: We talked a lot about the cover of the catalog, and it was a challenge for us because we were representing two artists in the show. We never saw a design that successfully integrated the two photographers.

JK: Yes. We were hoping that the designer would come up with something that would make use of one image by each photographer, but that didn’t work out. We finally put a Hamaya work on the back [“Children Singing in a Snow Cave, Niigata Prefecture”] and a Yamamoto photograph on the front. Graphically it works very well.

The motif of the image of the cage is something that Yamamoto used over and over. I don’t know if for him it was to represent the atomic bomb or not.

AM: Obviously it can be read that way with this particular image, but if you look at other images wherein he employs the cage motif, it’s being used as a symbol of imprisonment or censorship. That was one of the reasons that we liked it— it didn’t have one meaning. This image can be read as you said—as an atomic bomb cloud—but I think there are other ways to read it. It is over a city. We don’t know what city was depicted. It’s probably Nagoya because that’s where most of his city scenes were photographed. As such, it could represent his feeling of being trapped in Nagoya.

Why did you put Hamaya’s items first in the show? Do you think it’s easier to understand for the audience?

JK: I think one of the reasons was that Hamaya’s work is easier to understand. Chronologically, their careers start around the same time. but there were more pieces that were of a slightly larger size—although they are not enormous—by Yamamoto included in the show. And this back space in the galleries accommodates those pieces, it’s a large space with long walls, and they need to be filled, so we thought in terms of the installation design that Yamamoto would work better back here. And we wanted it to seem like two solo exhibitions. By breaking them up instead of alternating them or combining the work in galleries, that this helps us do that. We have so much space here to work with. It’s always difficult to come to a decision about that.

AM: I think it’s nice also to start with Hamaya, who is focusing more on traditional Japanese culture, and whose vision might align with people’s expectations of traditional representations of Japanese art and culture. I don’t know how many people would think of Surrealism and the avant-garde when they think of Japan, so I think they are surprised to come from Hamaya to Yamamoto. That surprise is in keeping with Yamamoto’s surrealistic tendencies.

JK: Yes, I think that Hamaya provides background, which is exactly what he wanted to do with his work. His purpose was to try to record some of the history of the country.

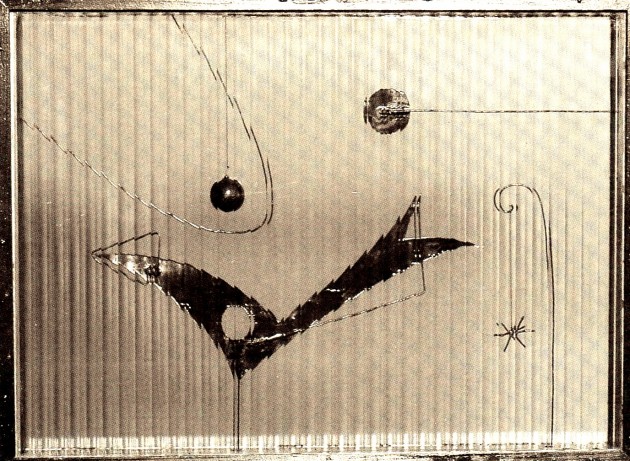

Some people think Yamamoto’s creative originality particularly lies in some of his series of photos, such as “My Thin-Aired Room” [shown below/cited at the conclusion of this interview*] and “The Man Who Went Too Far.” How would you describe the originality that you find in Yamamoto’s work? Is there any particular period that you find his originality especially vibrant?

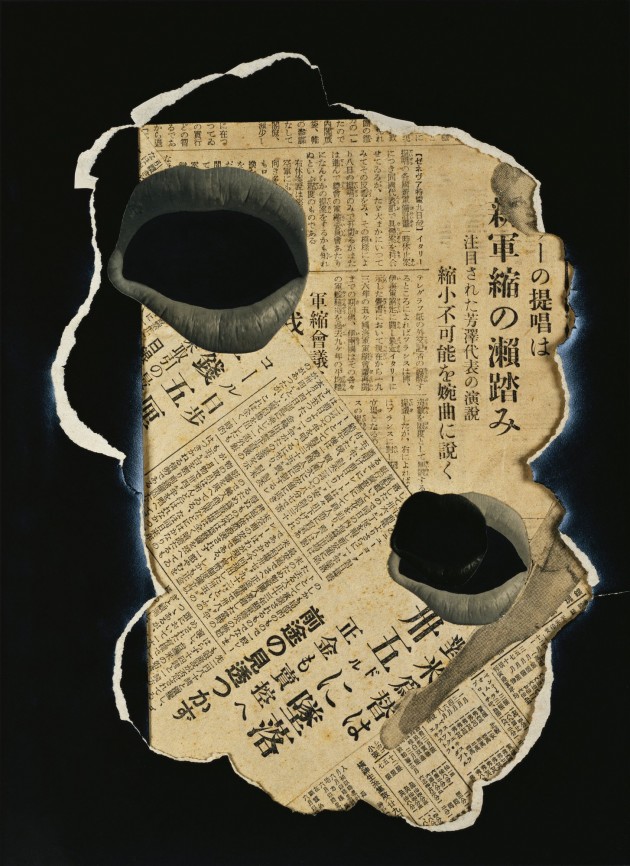

AM: I think there are two ways I would answer this question. The first is—and John Solt talked a lot about this point and I also think it is important—that Yamamoto was not only a photographer but also a poet and many other things as well. In the exhibit you can see his paintings and three-dimensional work. He was a translator from French to Japanese. And I think it is really important—and I hope that people see this in the show—that he thought of everything as very interconnected and interrelated. You see excerpts from poems and you see texts incorporated into some of the images that he makes. I think that is, in a way, how he is most original. He was someone who—throughout his career—thought about the relationship between so many different art forms and incorporated that idea into everything that he did. I don’t think it’s time specific. He was always interested in poetry, and he studied French literature and poetry in his youth. You see his interest in text in the very first series of collages that he made, one of which we have on view, where newspaper is being incorporated into the work.

I do think that for Yamamoto a very impotant period in his career was right around the time that he was censored, in 1938 and 1939, when he was creating poems and texts and including them in Yoru no Funsui as well as producing photographs at the same time. And when the special higher police interrogated him and freed him on the condition that he wouldn’t print that journal anymore, I think that changed him. It really motivated him to produce work that had more of an edge, that had political undertones in it. Everything had to be under the surface — symbolism was really buried in the work, but I think it’s there. If you go looking for it you can find it. I think out of that particular experience there was an explosion of really interesting work, collages, still lifes, really everything he did right around that time is very interesting.

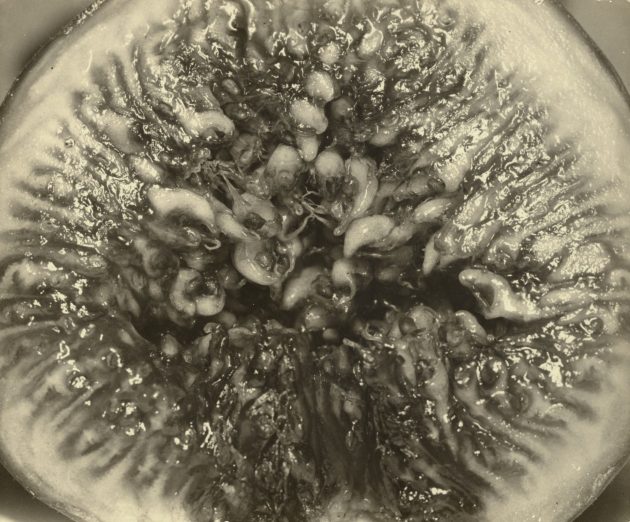

I heard that the Japan Foundation recently awarded you a grant to visit the studios of many Japanese contemporary photographers. Did that visit give you any new insights into Yamamoto’s photo production? For example in your catalog article you mention that Yamamoto’s close-up of a fig from 1933 was about 30 years ahead of Daido Moriyama’s similar in-your-face approach of shooting a close up of an object.

AM: Yes, I think that Yamamoto was a forerunner, an innovator, and he was ahead of such people as Daido Moriyama and Eikoh Hosoe. You can look outside Japan as well to find his influence. If you look at the series “My Thin-aired Room,” you see a reference to Duane Michals many years later. So I think Yamamoto was very important for people who came after him. Certainly Frederick Sommer is another example of someone whom you can look at in the same light as Yamamoto.

I traveled to Japan in January, and right afterwards I went to New York to see exhibitions at MoMA [Tokyo 1955-1970: A New Avant-garde] and the Guggenheim [Gutai: Splendid Playground]. It was interesting to see the links between the exhibitions I saw in both places, as well as to Yamamoto’s work. You can see from both the Gutai movement[7] and Jikken Kobo.[8] [“Experimental Workshop”]—there was a great show of Jikken Kobo work up at the museum of Modern Art in Kamakura — that things Yamamoto was doing in the 1940s or early 50s did make their way into what the Jikken Kobo group was doing, or even Gutai, in some of the performative things that were happening.

JK: For instance, the interest in transparent surfaces.

AM: Exactly. In this sculpture [“The Poetics of Space”, 1958], for example, you see the glass. There were related works in the Jikken Kobo show by Yamaguchi Katsuhiro and in the MoMA exhibition. They are directly related to what Yamamoto was doing and what came a little bit later. Surrealism was waning in the 1950s and 60s in Japan, and he was very much carrying the torch.

Takiguchi Shuzo[9] was the connection with what Yamamoto was doing. Takiguchi was a proponent of Surrealism in the 1930s, and then he was involved in Jikken Kobo. There is certainly continuity between the two.

Panels of Man Ray and Magritte are displayed next to Yamamoto photos. What has the audience reaction been to including those panels, do they find it helpful or a distraction?

AM: This is interesting and came up in the lecture last week [mentioned by Miryam Sas], about the reasons for or against including comparatives on the panels. My attitude toward the comparatives was twofold.

First, we know, for example in “My Thin-aired Room” because of Yamamoto’s sketchbook, that he was looking directly at that painting by Magritte [“L’homme au journal” (Man with a Newspaper), 1928]. I thought it was really important to show that he knew this painting. For me it showed that he was very well informed. He was very savvy, and that was an important part of who he was as an artist. He was well educated, and he amassed a huge library and looked at a lot of art books. I think it was a very directed influence.

The second point that I wanted to tease out in terms of including the comparatives was how Yamamoto diverged. I was actually hoping to focus on the conversation that was happening between two artists. Because that is what Surrealism was, it was a big conversation among a lot of artists. And I think that Surrealism as a movement tends to involve exchange between artists. There are exquisite corps[10] drawings and collaborations in the manifestoes, the texts, the poems and the books. I see [the movement] as more collaborative than derivative. While perhaps the design of [Yamamoto’s] work is similar to what Magritte was doing, the point of the work and the elements within the photograph were so different. And Yamamoto was pointing his commentary at Japan, which is something that Magritte clearly was not doing in his painting. I wanted people to understand that what Yamamoto was doing—especially in that piece—was talking to his native audience. I think maybe you can do that without the comparative, but it helps one to understand in terms of design and the history of art, that people are in dialogue, in conversation about how a work can be applied.

JK: We know that the impetus for Yamamoto’s Surrealist work and that of a lot of other Japanese artists of the time came from at least writings, if not visual imagery, from France, from Europe. It had to do with them greatly admiring the literature as well as the art in France, particularly. Everything French was the rage and it was part of the influx of modern ideas as well as fashion and everything else from the West that the artists were embracing, because they wanted to know what was going on in the world. Hamaya was turning his back on all of that, saying that it’s what is special about Japan that we should be representing. I think there are a number of reasons to make these direct connections.

In your catalog article you delve into Yamamoto’s “disobedient spirit” as you call it, you also describe the relationship between French Surrealists and Yamamoto as one between teachers and a disciple. I think it’s an interesting point of view but doesn’t it place Yamamoto in an inferior position of a one-way receiving of the teaching, rather than placing him in the context of the possibility of a more equal “dialogue” of artists?

AM: I don’t think I describe him as a disciple. First of all, Yamamoto is younger than a lot of the Surrealists who he’d been looking at since he was a teenager in the early 1930s, and he studied French literature—poetry—and art. I think it’s fair to say that he was a student of the movement.

In terms of a direct dialogue between France and Japan, that really didn’t happen, because relatively few people in France communicated back in Japanese. It was people in Japan who were studying French, as Yamamoto was, who were able to spread knowledge of Surrealism and translate it into Japanese. And that is what he did, he created the journal [Yoru no Funsui] where he was translating text. What I was hoping to say is that he was kind of a translator, he was studying a lot of this material so that it then could be disseminated to a Japanese audience and it could be put in a Japanese context. That’s what Yoru no Funsui is doing. Yamamoto was putting Surrealism in a context for a Japanese audience. It is not just about studying something and absorbing it, I think he was really interpreting Surrealism.

JK: Yes, and they were literally interpreting it in the French through Takiguchi Shuzo, who was older but was somebody whom Yamamoto very much respected because of Takiguchi’s energy and his progressive ways of trying to bring things to Japan, and he was interpreting it visually as well. I think that he may have been a kind of disciple to Takiguchi, but I don’t think that was so in terms of Man Ray or others.

AM: Yamamoto was a student in that he was curious and he was interested in learning about what was going on. That’s why he had books by Man Ray and André Breton and others to understand fully what Surrealism was. And certainly that comes out in the relationship between his work and the work of Man Ray or Magritte, but Yamamoto was doing his own thing. It’s not as if he’s some sort of copycat, he’s clearly doing his own take on what avant-garde means.

JK: I think we fall into the traditional [concept] that the West initiated it and is doing it better. That happens far too frequently and the point of the show is to let people know how the Japanese, another culture, was doing it in their own [not inferior] way.

AM: Because of the chronology of events with Surrealism exploding in France from the 1920s into the 1930s, we have to remember that Yamamoto was born in the 1910s. He was not yet 30 years old at the time when Surrealism was peaking in France. The Surrealist exhibit that Takiguchi organized didn’t come over to Japan until later, in 1937, which is just about the time that Yamamoto was blossoming into a photographer. I think it’s important to bear in mind the chronology here. It’s not so much about being a follower or a leader, it’s more about when Surrealism was really being embraced in Japan, which was right around the time that Yamamoto was maturing as a photographer. That’s why this relationship with him and Surrealism formed at the time that it did.

The Japanese see much of Hamaya’s work in a nostalgic way for a past that is dying or already lost. The Americans see these same photos with nostalgia for an exotic, wholly Other culture. In the final analysis, do these two nostalgias merge into essentially the same thing or are they fundamentally different? What is the attraction for the American viewers in Hamaya’s evocation of a “Lost Japan”?

JK: As you point out there is nostalgia on both sides, depending on whether you are a Japanese audience looking at the Hamaya images or an American. No, I don’t think it merges into one thing. At the time the pictures were made it was not only Hamaya as a Japanese person who cared very much about the culture and also was avidly interested in this new field of ethnography, and it was also not only about recording the past. But it was learning about something that was exotic for Hamaya. He grew up in the middle of Tokyo in Ueno, and his father was a detective. He was a city boy and also had started out—just as Yamamoto—in wanting to be as modern as possible.

I think that for the American audience, of course, it was—especially in the 1950s—of great interest because Japan was just opening up. So many American troops and servicemen had been there and gotten interested in Japan. Of course, it did also seem exotic because it was very different from traditional US customs or contemporary US life at the time. But I think that for Americans that has changed—at least I hope it has—in that the US audience now knows much more about Japan. And they should know more about the geography and everything else. And they would, in seeing this work, reflect about what remote areas of a foreign country looked like in the 1940s and 50s. I think it seems much less exotic now although still of interest. You would know better than me, but I think for a Japanese audience it is much more nostalgic. It is about a time lost, about an important time when war was on the way. For a US audience it would be much less about nostalgia as compared to the way a Japanese audience would see it.

If American viewers are indeed nostalgic for a culture that is not their own, then Hamaya’s “realism” in a sense takes on a “surreal” quality for them. Therefore, “Japan’s Modern Divide” from such an American audience’s point of view presumably can also be considered a divide between two types of surrealisms. What do you think?

AM: I think Hamaya made those images because people were not familiar with that lifestyle at the time, even then.

JK: Yes, yes. Hamaya talks about how peculiar it all seemed to him. He also talks about ethnography and how important it is, and he recorded many details on his trips, and he wrote the texts to the books that he published. He recorded practically hour by hour some of these rituals, but I think that at the same time he made all these trips back to this remote area because he was fascinated by this other culture, really. Because it was so entirely different from what he had grown up with. There is also the Kunio Yanagida book Tales of Tono[11] that had been published originally in 1910 but was reprinted in 1935, and then again in the 1960s. There was renewed interest in what Yanagida had done. He is the one who is given credit for starting the postwar field of folklore studies in Japan.

I’m trying to think of an American part of the US that would seem as different [as the back country of Japan is to Tokyo].

AM: I remember Anne Tucker saying that when she was in New York and saw a William Eggleston show. The woman standing next to her was looking at pictures of supermarkets and houses with dirt yards and saying, “Oh, how exotic!”

JK: Well, the south…Tennessee, Mississippi, parts of Georgia and Louisiana are very different from the rest of the US. I’ve traveled there, and the first time you go, you come out finding it harder to believe. I remember my father from Chicago for some reason talking about having gone south with his father and being surprised by the great differences.

There are some similarities [between the rural US and Japan], but I think people assume that because Hamaya was Japanese he knew all about the back country and just wanted to report about it, but that is not the case.

The department of photography purchased and received donations of Asian photographs from Japan, China and Korea. It seems like the focus of Getty is turning more towards Asia in recent years. Is this perception correct?

JK: I would say it is more so than it was five or six years ago. Our collection covers the entire history of photography, and we do not have a special fund for acquiring work from Asia, which I wish we did. Now it is an area that we are looking at each year as we acquire, and we’re looking also at many other things. Asia is an area that we are learning more about and that we want to give attention to. And that is a change, yes.

Is there a vitality that you perceive in the contemporary photography of Korea, China and Japan? How do you compare and contrast the activity going on in these three different countries?

JK: There is a huge amount of activity going on in all three. For China it is a new thing, relatively, it is fifteen years old. And in Korea it’s also relatively new, because they have had such a troubled history that has not allowed for much of a contemporary art market to develop, as well as having the kind of materials and equipment you need to produce art and photography specifically. But in Japan there has always been a lot of activity. There is a very old and strong tradition of great photography being produced.

Amanda, you made the rounds on your last trip, so you are more up to date than I am.

AM: I think that, even though there has been a long history of Japanese photography, it has been only within the last 20 years that there has been a museum of photography in Tokyo [Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography]. It’s important to realize that this long tradition hasn’t always been incorporated into museums and exhibition galleries. There hasn’t traditionally been a market for photography in Japan, either. Even though the tradition of photography is vast and rich in Japan, in terms of getting work into galleries and museums, that’s a pretty new development.

JK: Yes, [in Japan] since 1990s, the last 20 some years. But each time we go back there are more galleries, it seems.

AM: More galleries, more shows. And I think that photography is starting to get incorporated into more things. For example, when I saw the Jikken Kobo show, there was photography in it. It wasn’t put to one side [but was integral].

JK: The MoMA show didn’t do as well. They had quite a bit of photography but it was all crowded together in the last room.

AM: In terms of exhibitions in Japan, I think a lot of the photographers who have been working for a long time, but have not had a chance to be represented with a monograph and exhibition, are now being shown, and their whole careers are being shown, which is great.

JK: And there is certainly more attention within the US [to Japanese photography] in the last couple of years. We are happy about all that.

Relatively little attention has been paid to Japan’s postwar art in the West. However, the recent attention surrounding postwar Japanese art such as in exhibits of the Mono-ha[12] and Gutai groups seem to have created a boom in the subfield of Japanese art within the present-day American art scene. Do you think the positive reception to your exhibit here is part of that wave? Why do you think that this boom is taking place now and didn’t occur previously? Is it part of a growing interest in Asian art in general, or is it more regionally based in east Asia? Or, rather, is it specifically about Japan?

JK: It’s a good question about why now. The interest in Chinese art and the great productivity happening there, as well as the market attention to China has helped. That has been going on for the past ten years now, and it has helped bring attention to Japan, Korea and other places. It’s all of the East Asian countries and more.

I haven’t talked to people at other museums to know why now. It’s an interesting question, because it’s always been worth the attention, it just hasn’t gotten it. It may also have something to do with mobility, with the fact that there are now many non-stop flights between the US (especially Los Angeles and San Francisco) and Seoul or Beijing or Tokyo or other parts of Asia. It’s very easy to get there. The market, the internet and China’s rise have contributed to the interest in Asia.

AM: Some of these things are cyclical. There have been shows like the one Marc Holborn did in London [“Beyond Japan: A Photo Theatre,” 1991], and there was Scream Against the Sky [“Japanese Art after 1945: Scream Against the Sky,” 1994], the same person who organized that show, Alexandra Munroe, organized the Gutai show [“Gutai: Splendid Playground,” 2013]. There was a big show in France in the 1970s of avant-garde art in Japan, but it takes time. Many of these [avant-garde-Japan related] exhibits have collided within the last two years [in the US: MoMA, Guggenheim, Getty, LACMA, etc.]. I don’t know how many conversations were going on between museums about them.

You’ve been working with these Yamamoto/Hamaya materials for years. Right now, which photo by Hamaya and which by Yamamoto attract you the most?

AM: For me it’s been great to have this particular work here [“The Developing Thought of a Human… Mist and Bedroom and”], which is the earliest work in the show. It was one of three collages that he made, and it is the only one that survived. It’s just nice to come and look at it. It’s really great to have it here and to have it add to the context of what Yamamoto was doing, because this was made at age 18. You can see that he was playing with collage with Surrealist themes and ideas, and also he’s incorporating texts, and he was thinking about politics because the newspaper articles refer to political events. For me this encapsulates a lot of what Yamamoto went on to do.

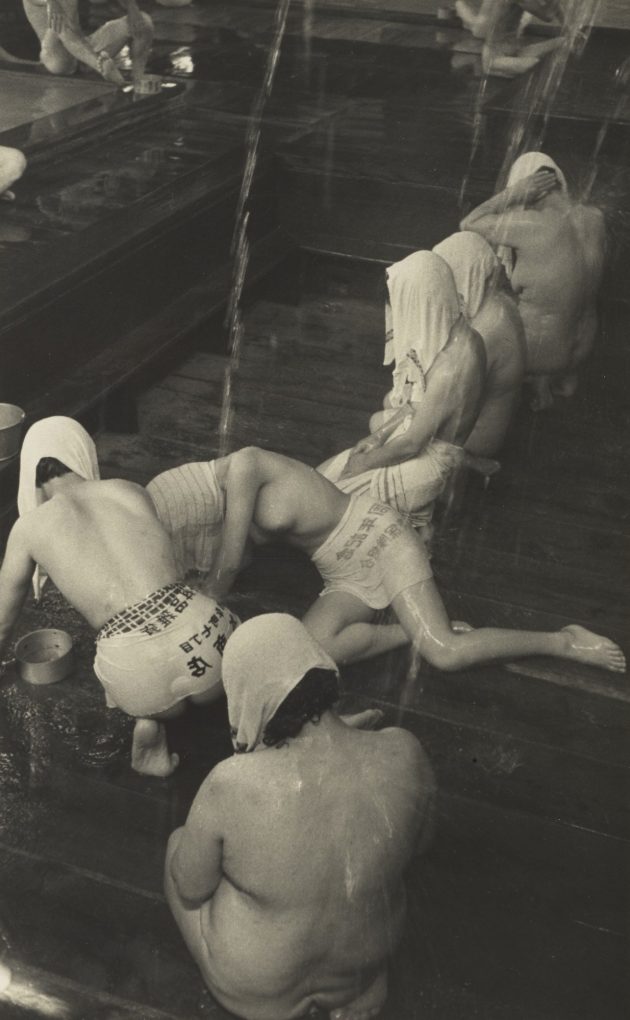

JK: I was very happy when I was presented with a whole group of vintage prints that Hamaya did at the “Sukayu Hot Spring” [“Sukayu Hot Spring, Aomori Prefecture,” 1957]. I think all the compositions are wonderful. I think this would be my choice. For me they refer back to the great woodcut prints of the 18th and 19th centuries of Japan. Also, in the history of the nude they could stand up to anything else. They are very informal studies, but it’s hard to think about these as strictly documentary pictures. They are some of Hamaya’s images that most reflect his artistic tendency as well as the documentary.

I heard that you are interested in exhibiting other Japanese photographers in the future, is it true? If so, is that because this was such a conspicuous success that you want to do more Japanese exhibitions?

JK: We hope it is a success, but the reason for showing more is that there is so much great work to show, and we hope to be acquiring more work. Our exhibitions always start from work that we have in the collection, and we have managed to acquire just a few works by Hamaya and Yamamoto, now about five years ago. We want to do larger shows in the future of the work by other photographers whom we have in the collection. I think we have work by about 20 [Japanese] photographers in the collection by now.

Amanda and I have a couple of ideas for something that wouldn’t happen for about two years, and next year—in about six months from now—we’re doing a Sugimoto Hiroshi exhibition, which will be built around pictures that we’ve acquired, as well as pictures that the artist himself is donating to us this summer. We’re excited about that. The Japan Foundation has awarded the museum a grant to help support that exhibition. Good things will come out of all of this.

Thank you very much. I didn’t expect to take so much of your time. You were very polite, and both of you have profound insights and deep knowledge, so I’m very grateful.

* “My Thin-aired Room” (1956) by Kansuke Yamamoto, gelatin silver print, © Toshio Yamamoto, Private collection, entrusted to Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography.

Notes:

1. John Solt is a poet, award-winning translator and independent scholar who has been Associate-in-Research, Edwin O. Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies at Harvard University since 1990. He is known as the authority on Kitasono Katue’s artworks and poetry. He wrote the definitive critical biography of Kitasono Katue, Shredding the Tapestry of Meaning: The Poetry and Poetics of Kitasono Katue (1902—1978) in 1999, and its Japanese translation was published in 2010. In 2001, he co-curated (with Ryuichi Kaneko, guest curator at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography) the exhibition “YAMAMOTO Kansuke: Conveyor of the Impossible” at Tokyo Station Gallery.

2. Paris Photo Los Angeles: Europe’s most prestigious photographic art fair which is usually held in November in Paris. For the first-time outside of France, Paris Photo made its inaugural debut at Paramount Pictures Studios from April 26-28, 2013. The fair showcasing a huge variety of historical and contemporary photography attracted over 13,500 visitors.

3. Ann Wilkes Tucker is the Gus and Lyndall Wortham curator of photography at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, where she has worked since 1976. Under her initiative, the museum’s photography department now houses a rich collection of over 28,000 works from all seven continents. She has curated over forty exhibitions and Time Magazine honored her as America’s Best Curator in an issue devoted to “America’s Best” in 2001. Her most recent curated show is “WAR/PHOTOGRAPHY: Images of Armed Conflict and its Aftermath” which started in November 2012 at the MFAH and travelled to the Annenberg Space for Photography in Los Angeles (March-June, 2013). The exhibition will travel to museums around the U.S. through 2013 and early 2014. Other exhibitions include “The History of Japanese Photography” (2003) and “Chaotic Harmony Contemporary Korean Photography” (2009).

4. Toshio Yamamoto, Kansuke Yamamoto’s son who inherited his father’s works which have been carefully and reverentially preserved since the great photographer’s death in 1987. Toshio plays a significant role to keep his father’s spirit alive in the Japanese photography world.

5. Tsuguo Tada is the manager of the Estate of Hiroshi Hamaya. He is the editor for one of Japan’s major publishing companies, Iwanami Shoten, where he founded the Fine Arts & Photography department. He has also curated and overseen a number of photography exhibitions in Japan and abroad.

6. Getty’s lecture: “A Conversation about Surrealism in Japan” was held on June 5, 2013 where Miryam Sas, professor of comparative literature and film studies at the University of California, Berkeley, interacted with John Solt. Moderated by John Tain, assistant curator at the Getty Research Institute.

7. The Gutai group is the post-war radical collective that broke barriers of social life and art in the mid-1950s through the early 1970s. Gutai artists brought performance-based works into public spaces with their smashing paint bottles, wrestling with mud and ripping paper screens to shreds.

8. Jikken Kobo is a post war avant-garde group founded in Tokyo in 1951. The group, led by the poet and art critic Shuzo Takiguchi, experimented with multimedia and cross-genre work including installations, music, dance, theater and short films.

9. Shuzo Takiguchi (1903-1979) was an influential poet, art critic and artist, who introduced Surrealism to Japan in the 1920s. In 1937, he organized the seminal Surrealism exhibition in Japan with the support of European Surrealists. In 1940, Takiguchi published the first monograph on Joan Miró in the world. His main artworks were the series of decalcomania which he created around 1960.

10. A collaborative artwork or poetry in which people write a phrase or draw an image on a sheet of paper, then fold it, hiding the writing or drawing, pass it on to the next person and continue the work until every collaborator adds to the composition in sequence.

11. Kunio Yanagida was a Japanese scholar who is known as the great authority on Japanese folklore studies. He collected folktales and legends from local residents in Tono, Iwate Prefecture and published them in his book Tales of Tono in 1910. It has become a literary classic and has had profound influence on Japanese literary and artistic circles.

12. Mono-ha is a group of artists, active in the late 1960s through the mid-1970s, who made large-scaled sculptures incorporating natural materials with industrial objects such as stones, wood, paper, cotton, steel plates and paraffin. The group attempted to draw artistic expression from unprocessed objects and untouched materials. The Mono-ha movement is often compared with Minimalist art and Arte Povera in Italy.

Eiko Aoki is a freelance journalist and researcher covering Pacific Rim arts and specializing in photography. She was a translator for the sports section of the Asahi Shimbun (a Japanese-language daily newspaper). Later she became an art and culture writer for the Japanese edition of the International Herald Tribune (now the New York Times). Her bilingual work has appeared in Trans Asia Photography Review, LACMA, Sei’en, and elsewhere. She lives in Kyoto, where she co-edits the Kenneth Rexroth Reader (in Japanese) and writes her popular blog, http://artthrob.exblog.jp