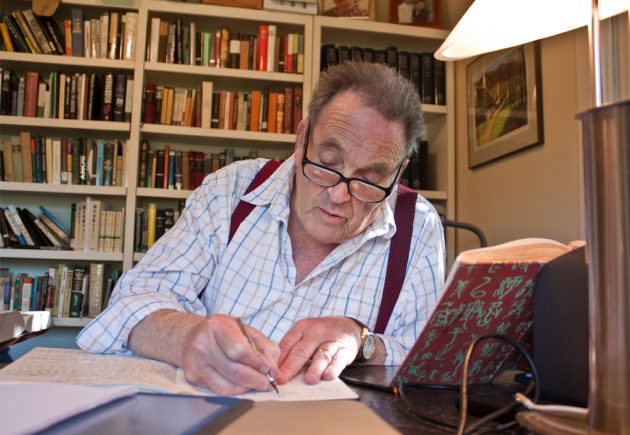

Last April, in the late afternoon, while magic-hour light poured through the bay window opposite his desk, I watched the greatest translator of Japanese literature at work translating its most important modern novel, heretofore undiscovered by readers of English; at age 72, perhaps his last feat of ambition, and, if nothing else, a marker in time as his era finished passing, friends and patrons along with it. Granted, I was photographing, and the moment’s authenticity was simulated. Nor does there exist a greatest translator, just a handful of arguable candidates, and John Nathan is one of them. Regarding the novel, some historiography is necessary:

In 1916, Natsume Soseki wrote his final novel, Meian (Light and Dark). Or failed to – he died without finishing. 166 sections had been serialized in Asahi Shimbun. Another 22 waited on his desk. Both of his English translators have told me there’s a hard edge in the final sections, a declension in the prose, written as Soseki’s ulcer-riddled stomach began to collapse.

Some time would pass before modern literature was recognized as a fit subject for intellectual discourse in Japan, but for our purposes it’s enough to know that Japanese writers and scholars across generations have regarded Meian as Soseki’s masterpiece, albeit a difficult one. Even unfinished, Meian was long – easily the equivalent of 600 English pages. Yet it contained little dramaturgy; Soseki had been coaxing his work into negative space, and most of Meian occurrs in the protagonist’s quotidian social interactions, all of them freighted with suppressed desires and petty expectations. Characters’ every feint and dodge, every blow delivered or received, is restricted to conversation and social gesture.

The novel represented a Jamesian leap for realism in Japanese literature, but it was more desolate than James; from the writer Eto Jun called a “critic of civilization,” this topography of social constraints (as John Nathan describes it) frustrated critical attempts to locate a kernel of self-determination or transcendence in the text. It epitomized the elements of Soseki’s genius that caused Norma Field to wonder (in the afterword to her translation of Sorekara) if Soseki’s work – so intimately connected to Japan’s jarring lurch toward modernity – could ever be understood abroad, where modernity had been sewn from comparatively whole cloth.

Western readers have never warmed to Soseki in a manner commensurate to his stature in Japanese letters, and often don’t seem to understand what there is about his work to like. A handful of American authors have said as much, most notably John Updike, who declared himself unmoved by Soseki’s canonical work in English translation, Kokoro. Western scholars and translators, for whom the ability to encounter Japanese literature in its native context is ostensibly essential, have been dismissive of Meian in particular. A roll call of influential translators (Seidensticker, Keene, McClellan and Rubin included) have proclaimed the novel worthy of indifference. Keene said it bored him “from beginning to end.”

American translators’ Meian allergy is less surprising if viewed in historical context, against the backdrop of Japanese literature’s English language golden era, when Knopf attached itself to Tanizaki, Mishima and Kawabata, three authors whose writing hews toward western stereotypes about Japanese literature, namely that it thrives on ambiguity and concerns itself with beauty. Meian offers neither vagueness nor an aesthetic core. It is relentlessly analytical and precise, even when the Japanese language can’t be; with Meian, Soseki had taken a hammer to Japanese literature’s prosaic tendencies in an effort to make form align with content. Meian’s construction is at once a reflection of the transformative tension that saturated the modern Japanese psyche, and an unwitting rejection of latter-day translators’ aesthetic preferences.

The book’s only English translation, by Valdo Viglielmo, was published in 1971. It went out of print in 1976, and for 41 years no one else attempted one. Viglielmo, who was a military police officer in Tokyo during the occupation, taught at the University of Hawaii from 1965 until his retirement in 2002, a career which included dual disappointments: Soseki’s lack of international stature and Meian’s absence from Japanese literature’s translated canon. Viglielmo revisited his translation and self-published a new edition in 2011 with help from William Ridgeway, a former doctoral student.

Not long before Viglielmo published his new edition, John Nathan was reading Meian for the first time and finding himself compelled by the apparent impossibility of producing an adequate translation. Readers of Kyoto Journal will be familiar with Nathan’s work. The youngest primary contributor to Japanese literature’s initial English language florescence, Nathan produced comparatively interpretive translations of Mishima and Ōe that offered readers a level of standalone literary value rarely seen in English translations of non-western literature. Many credit his translation of Kojinteki na taiken (A Personal Matter) with fueling Ōe’s Nobel candidacy. He is now the last practicing writer-translator from a canon-defining era when literary aspirations, not scholarly rigor, bound most translators of Japanese literature together.

Today, almost all translations of Japanese literature pass through academia, in the form of funding, publication or professorial authorship. John Nathan’s forthcoming translation of Meian is no exception. It will be his first book-length translation to appear through a university press when Columbia publishes it in November. Inclusion in Columbia’s catalogue all but assures it will be canonized, albeit for a small, specialist readership. This is what any translated Japanese novel not written by Murakami or his cohort can hope for, even a novel of historic significance translated by a world-class talent.

In his office, when the good light had waned and John had grown restless with his simulated gestures, I had to ask: “What exactly are you expecting this book to do?”

“To carry me back into the game,” he said.

“What game is that?”

“One worth playing, I hope,” he said. “Worth reading.”

* * *

As a gesture toward comprehending Meian’s merits, try to recall an interaction from your own life which, if the dialogue had been recorded, would have appeared banal, but which you knew to be tortured. A water cooler interaction with your boss and its anxious subtexts. A petty but bruising disagreement with your significant other. A nearby observer might intuit the weight of those moments, but what about an observer many times removed: first by language and culture, then by a century of accumulated changes in social custom?

Meian presents English readers with an equivalent gulf, and its translators with a corresponding challenge. If there’s a bridge in the text, his name is Kobayashi, and he acts as Soseki’s agent provocateur. During my conversations about translating Meian with John and Val, a number of common resonances emerged, including a shared sense that the novel itself is something like an ornate lock, and that Kobayashi is the key that turns inside it.

Kobayashi appears throughout the novel to nettle the protagonist, Tsuda, his effectiveness derived from knowledge of Tsuda’s desire to reunite with his former fiancée, of whom Tsuda’s wife (O-Nobu) knows little. In one of the novel’s pivotal scenes, Tsuda and O-Nobu have decided to give Kobayashi some farewell money to ease his impending departure to Korea. Kobayashi provokes Tsuda by trying to give the money away moments later, and by hinting that he might have disclosed Tsuda’s hang-up to O-Nobu. Much of the scene unfolds while Kobayashi subjects Tsuda to an extended lecture, the topic sentence of which amounts to one of the clearest textual articulations of Soseki’s critique of modernity: “You’ve got so much freedom you don’t know what to do with it.”

To Tsuda, and to readers, the perfervid, quasi-Marxist Kobayashi offers the dual enticements of modern existentialism: everything matters, or nothing matters at all. For his part, Tsuda offers Kobayashi an unselfconsciously modern psyche and its myriad vulnerabilities. On the way to meet Kobayashi, he window shops without paying attention to what he’s looking at, experiencing only detachment until he notices an imported necktie he likes, and feels compelled to enter the shop so he can touch it.

Of Kobayashi’s role, Nathan said, “Through this incredible web of dialogue and confrontation, Soseki reveals a topology unlike anything else in Japanese literature. Where Soseki doesn’t do it, Kobayashi does it for him.”

Viglielmo said, “Kobayashi is Soseki, I think, speaking to the reader with a directness he never permitted himself.”

John and Val also share a favorite scene, earlier in the novel. Tsuda has bought an air rifle for his young cousin, Makoto. As they walk from the toy store to Makoto’s house, the boy tells Tsuda that his father has forbidden him from playing with a wealthy schoolmate. Tsuda makes light of what Makoto has already admitted: when Makoto comes home from playing with his wealthy friend, he pesters his father for the luxury items the other family can afford. But Makoto appears shocked by Tsuda’s ribbing, and runs ahead down the road. When Tsuda nears his uncle’s house, he hears the pop of the air gun, and turns to find Makoto hidden in the bushes, aiming the rifle at him.

It’s enough to note that John and Val are both socialist-leaning translators of Japanese literature who have embraced the special merits of the same novel, likely to take satisfaction from that novel’s proudly unsophisticated provocateur, or from a scene in which an early imposition of class consciousness compels the young to play at murdering the old. But one could also note – and he might feel compelled, given the similar things the two have said about the neglected masterpiece on which they’ve staked their respective legacies – that they’ve met before, at a formative moment.

* * *

On page 3 of John Nathan’s memoir, he is a newly arrived, indecisive undergraduate at Harvard:

That week, I sat in on a class in modern Japanese literature taught by a voluble Italian-American named Val Viglielmo. Viglielmo was a virtuoso. He was lecturing on Ichiyo Higuchi, a novelist who had written poignantly as a very young woman about life in the pleasure quarter in the late nineteenth century. As he introduced her he chalked on the board the characters for her name and the titles of her work with a swift, showy unerringness that inspired me with admiration and envy.

Yes, Voluble. Viglielmo is the product of centuries of Waldensian Protestantism and leftist politics. As a military police officer in occupied Japan, he attended the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, where he sat in the gallery and thought to himself that the Emperor should be on trial, too, if they were going to try anyone at all. That memory returned to him in 1990, when, in his capacity as chair of the East Asian studies department at the University of Hawaii, he attended a reception for the new emperor and found himself pondering a historic lunge for the emperor’s throat. Because Val is the only member of his generation of Japan scholars who consistently used his literary and intellectual activities as a platform for opposing reactionary political elements in Japan, and because he has risked his career in the process, I like to picture him mid-lunge.

Val had been offered the opportunity to complete his graduate studies at Harvard in 1948, but had deferred in order to return to Japan, where he traveled and taught, along with his wife, Frances, eventually settling for a while in Nagasaki. There, he helped clean up the bombing site and build a park, in the process befriending a girls’ school principal who would die suddenly a year later of radiation-related illnesses.

At Harvard, Vigliemo found himself more at ease with Serge Elisséeff, an early pioneer of Japanese studies in English, than with Edwin Reischauer, the future ambassador to Japan who had once been Elliseef’s student. Elliseef was soft-spoken, his English accented; students gravitated toward Reischauer, the main act, and Viglielmo’s association with Elliseef put him at the periphery of an emerging social hierarchy in post-War Japanology.

Though incidental, Viglielmo’s appearance – at the height of his considerable enthusiasm – in front of John Nathan, was opportune. In a later interview, Nathan said that if he’d been exposed to Chinese around that time, he likely would have studied it instead.

Synchronicity would have it that when I visited John Nathan in Santa Barbara, he was teaching two classes: one on Soseki, and the other on Higuchi Ichiyo, whose name and works drew him into the Japanese language when he sat in on Viglielmo’s lecture. Nathan, too, is a voluble educator, whose gift for temporization – including an impressive brogue learned from Katsu Shintaro – carried the class I watched him teach in April.

Afterward, we walked across campus to his car, and he thought to mention Val. John held Val in esteem and was nervous about how he would feel when he learned a new translation was forthcoming.

* * *

In May, John attended a celebration of Barney Rosset’s life and work at Cooper Union in New York, accompanied by his wife, Diane, and their children. Rosset had died at age 89 in February after heart valve replacement surgery. A montage of pictures of Barney at pinnacle moments, or with the literary geniuses he’d brought to America’s attention, played on the stage at the Great Hall. A succession of friends, family members and favorite authors offered remembrances. David Amram played Amazing Grace – or at least that’s how it began – on the shakuhachi.

Though one can’t debate American readers’ historical indifference to translated literature, Barney Rosset’s lifework spoke better of America’s transcultural impetus. While most will remember him as the central figure in the defeat of literary censorship in America, he also expanded American readers’ cultural palettes; he brought four Nobel laureates into English, including Ōe Kenzaburo, who had to be enticed away from Knopf. Ōe brought with him a promising young translator named John Nathan, who – though he worried about angering Knopf – had already dared to jilt Mishima Yukio in order to make time to translate Ōe. Rosset later called Nathan the greatest translator of his generation, and Nathan would sometimes reflect on a quiet point of pride: his son, who attended billiard games in Rosset’s basement, had noticed that Barney kept a shelf in his bookcase reserved for John’s work.

If there were any young people except for immediate relations present at Barney’s memorial, neither I, nor John, nor his family could find them. The evening offered at least one other reminder that little passes between generations, and that memory is a fitful organ: When the event had ended, many other attendees were surprised to see John mingling, and had assumed – because current Grove president Morgan Entrekin had read the letter Ōe Kenzaburo sent – that he hadn’t come.

* * *

In the lobby of the International House in Tokyo hangs a framed photo of John Nathan with Donald Richie, Edwin McClellan, Howard Hibbett and Edward Seidensticker, taken 14 years earlier, on the eve of a literary translation symposium they paneled. Last September, Richie was among the veritable class reunion of old Japan hands in attendance at an I-House taidan between John Nathan and Mizumura Minae, about Meian. Sam Jameson, elder statesman of expatriate journalism in Japan, was there, too. It was the last time John would see either of them – Donald died in February, Sam in April.

The event, held in Japanese with simultaneous translation into English, was John’s first time speaking in public about Meian in particular. Since arriving in Japan blank days earlier, John had attached himself to Mizumura, whose Zoku Meian (Meian Continued), published in 1990, brings Soseki’s novel to a speculative conclusion. Mizumura herself is a component of the bridge connecting English and Japanese letters. She was raised and educated in America, and much of the dialogue in her second book, An I-Novel from Left to Right, is written in diegetically verismilar English.

A capacity crowd of approximately 250 attended the taidan. By then John and Mizumura had established a rapport – a naturalness that played well on-stage as they articulated their respective understandings of the novel. John’s genuine awe for Soseki’s virtuosity pleased an audience whose questions for Mizumura carried nostalgic, nationalist undertones; among mainstream Japanese readers, Mizumura is best-known for a book of essays lamenting the deterioration of the Japanese language, which she blames – at turns – on the influence of global English. John had also gone to see the Meian manuscript earlier in the trip, and shared a revelation from the visit: it wasn’t clear whether the last lines of the novel had been written in Soseki’s hand, and why a word had been added ex-post-facto (hitori de – alone). “I wanted to know why the characters had been added,” Nathan said. “If you can’t understand, you can’t translate.”

When asked why he translated Meian, John tried a little bit of humor. “When I read the old translation,” he said in Japanese, referring to Viglielmo’s, “I was hoping it would be good, so I wouldn’t have to do it myself.” The audience was tickled.

That Sunday, I met John in Ginza, where it was easy to imagine him as a young writer in the midst of his own development. It was raining, and we ate at the Lion Beer Hall. “This place hasn’t really changed,” he said. I thought it would be unfair to point out that it had, in fact, been franchised, and one could experience Lion Beer Hall at Narita Airport (and elsewhere) if he so chose.

John expressed enthusiasm for Mizumura’s reading of his manuscript, pointing out, for example, that he’d been struggling with a particular sentence, and that no scholarly explanation for it had satisfied him; Mizumura had quickly identified it as a deliberate echo of a similar construction earlier in the text. “That’s the kind of thing – only a writer can spot that,” John said. “She’s a bridge to genius.”

He was also satisfied with the taidan, and took it as evidence of a successful return: to his use of the spoken Japanese language as a tool for interpreting literature, to literary translation after an extended absence, to a public life of letters. “I hadn’t performed in a while. I was anxious. And you step out into that room and you can tell people don’t know what to expect. But you get out there and lay down a mulch of words, and people start to wrap themselves into it. Actually, I really love that,” he said. “And I was glad it was at I-House. Going to that place is like an archaeological dig for me. It’s a palimpsest of memories. I’ve misbehaved on those premises on every imaginable level.” The sensation of return is an odd one, he said, and described the dissonance of occupying a familiar space, with familiar people, all of whom had grown old, and some of whom he had partly forgotten. “People approach me and say, ‘Remember when we did this?’ And, honestly, I don’t anymore.”

We left the beer hall. While we walked down the Ginza toward the station, he pointed out places that were once important hangouts for literary types, including the former Bar Gordon, a bundan favorite where he’d drank with the likes of Kawabata, Tanizaki, Mishima, Endo, Ōe and Abe Kōbō, and where he’d begun his friendship with Hiroshi Teshigahara. He insisted on walking in the street, not on the sidewalks. “This is more fun,” he said. “It’s like Madison Avenue closing in New York. I always loved it.” As he entered the street, the wind shifted, blowing rain onto him, but he didn’t seem to notice. “This place,” he said, taking long slow steps, taking his time.

* * *

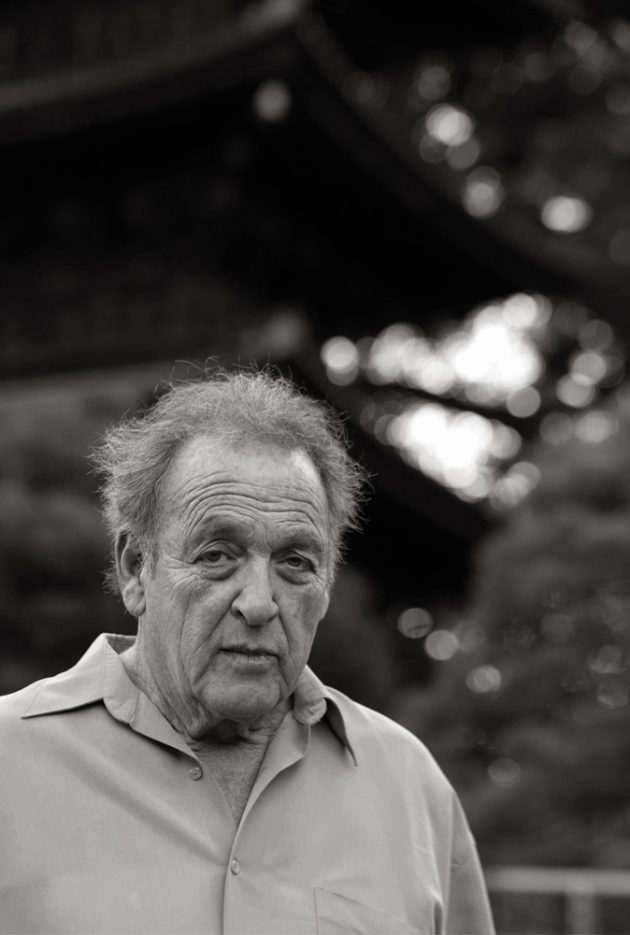

Except for the slight quaver in his voice and the visual indications of age, Valdo Viglielmo could still be 19 years old, as he was when a troop ship bore him into Yokohama for the first time. He’s all hands and eyes. He gestures continuously, grasping at air in the throes of an explanation, or turning his palms up in disbelief. One thought interrupts another; his stories begin and end concentrically.

Val’s life story is not unlike those contained in Soseki’s novels, arcing across the abrupt edge between two eras (before and after the bomb), etched into Val’s memory as a series of deep impressions. He was in military language training at the University of Pennsylvania when the first bomb was dropped. The news came in via radio, and the class was jubilant. A box of cigars appeared, and a bottle of champagne, which the instructor uncorked. “I remember feeling this sudden joy,” Val said, “because we knew we weren’t going to die.”

When his troop ship first docked in Yokohama, Val thought he saw a monster off in the distance, its skin crawling with insects, shambling toward the port. It was a trolley car, and the insects were people climbing over each other to avoid being thrown when it moved. “I was confused, and it made me realize I hadn’t the slightest idea what kind of misery these people were really enduring.”

Whatever the effect of John Nathan’s new translation, Val deserves credit for being the first (and, for a long time, only) English reader to recognize then novel’s rightful place within Soseki’s oeuvre. I don’t think this is an accident. I regard Val not only as a scholar and translator, but, more importantly, as Soseki’s best reader. Some of this can be explained by his close hereditary association with Soseki: Serge Elliseef was a deshi of Soseki’s; and Val’s mentor in Japan, Komiya Toyotaka, is widely believed to be the basis of Kokoro’s narrator-protagonist. Some of it can be explained by the earnest dedication Val applied to his repeated readings of Soseki, beginning with his purchase of Soseki’s complete works at a Jimbōchō bookstore in 1948.

There’s also a deeper consonance. When I asked Val why it matters whether English readers know Japanese literature, or Soseki, or Meian, he began by articulating the conventional merits, and then digressed, as is his tendency, and told this story:

“That was when I had the experience,” he said. “There was an elderly woman, and I was chatting with her, and then a young woman, 39 years old. She was the niece of the woman to whom I was speaking. And she said in Japanese to her niece, ‘He came with a group from Hawaii.’ And the niece, not knowing that I knew Japanese, said to her aunt, ‘Hawaii is part of the United States.’ Then she – oh my God, I get goose bumps – she looked at me with absolute hatred. She said, in Japanese, not knowing that I understood, ‘Otosu o to otosareru o daibu chigaimasu.’ ‘There’s a tremendous difference between those who dropped the bomb and those on whom it was dropped.’ She said it, and tears came to my eyes, and I didn’t know what to do, I didn’t know what to say, because I had overheard what her real feelings were, and it was said in an incredibly powerful way.

“I remember what I thought: What can I do? What can I do? What can I possibly do to show that I understand? And it turned out that her father had been killed. The brother of the woman I’d been speaking to was the father of the niece, and he had been killed, and she had seen him die.

“I said to myself: I have to do something to help her. The buses were forming to go back to the hotel, so I made sure that I got on the very bus with her and her aunt. And I even managed – indeed I almost forced myself – to sit next to her. And she was quivering with rage, just terribly, terribly upset. By now she knew I understood Japanese. So she said to me, ‘I’m not like my aunt. My aunt can forgive. I can’t forgive. I hate you.’ She expressed her rage and outrage and how terrible it was, and no matter what she couldn’t forgive me. And all I thought was: Let her say what she wants. Let her call me anything under the sun. Let her look upon me as an absolute worm or insect, if she can get rid of some of that hatred. If I could just absorb some of that hatred. If she could have a little more peace.” Here Val’s eyes widened, as if the moment were unfolding again in front of him, and he began to weep. “Because I felt I was responsible. My country had done that to her. My – her – oh my – even thinking, even talking about it now, here we are now, 1978 to 2012? It’s…it’s inscribed on my soul. ‘Otosu o to otosareru o daibu chigaimasu.’ ” Val began to shake. He lifted his hands as if to cover his eyes, but stopped short and stared at his palms.

Before and after telling it, Val framed this story with noble notions: We read stories from other times and places because we are otherwise doomed to commit the harm they warn against – to each other, to ourselves, to a hundred thousand human beings at once.

It occurs to me as I write this that I interviewed Val in a coffee shop on that day. He told his story over the clatter of ceramic cups, the hiss of espresso machines, and the strains of soft jazz that murmured out of the shop’s stereo system. When we were gathering all his photographs back into their albums and getting ready to leave, he said he hoped he hadn’t seen Japan for the last time. He talked about the places he remembered best, and wanted to see again. “Have you spent much time in Ginza?” he said.

* * *

I last talked to John Nathan in August. He was happy with the cover art for his translation of Meian, and with the incorporation of Shunsen Natori’s original drawings (from Meian’s serialization in the Asahi Shimbun) into the manuscript layout. The book, originally dedicated to Donald Richie, would now be dedicated to John’s son, Jeremiah, who had passed away in a free-diving accident in January. John was living in the Sierra Mountains at his second home, he said. He was hiking every day. He had also completed a detailed book proposal for a critical biography of Soseki in English, and had submitted it to his literary agent. Soseki’s absence from global literature’s pantheon called out for correction, he said. His rhetoric had come to resemble Val’s. “This feels at once very wonderful, and familiar, and new,” he said. “When I translated Ōe the first time, I had the same feeling, of the enormity of what I’d tried to do. And of course, that was almost nothing, if one thinks of it compared to Meian.”

Of Soseki in general, and of Meian in particular, the world may soon think better, or at least a little more. Edwin McClellan reversed his position on Meian before he died, acknowledging that he’d failed to see that it was likely Soseki’s shrewdest observation of modern anomie and self-centeredness. More recently, Reiko Abe Auestad published ‘Rereading Soseki: Three Early Twentieth Century Japanese Novels,’ a scholarly work that offered a more contemporary reading of Meian, and that examined the historiography surrounding its previous failure to engage western readers (including scholars, critics and translators). Because Soseki’s oeuvre shares a common task with critical theory (the critique of modernity), Soseki has also emerged as a preferred author for literary research among scholars influenced by the Chicago school of East Asian studies. And Soseki’s Botchan was published as a Penguin Classic in March. Most hopefully, The University of Michigan will host a Soseki conference in April, 2014. A single author conference is a rare event in East Asian studies. John Nathan will be the keynote speaker.

I spoke with Val again on Hiroshima Day, a year to the day since I’d met him. He had lost none of his buoyancy, and he bemoaned the growing assault on the Japanese constitution – including Article 9 – with characteristic vehemence. I mentioned that the Japanese military had chosen Hiroshima Day to unveil the largest naval vessel in the nation’s history. “That’s disgusting,” Val said. “Just disgusting.” He fairly spat the word. Vigor aside, what news he had to share was unhappy: his wife had taken a bad fall, and though she was now stable, her failing health had taken up most of the year since I’d seen him. He, too, at 86, was beginning to feel weak, and to suffer health complications.

Val had learned about John Nathan’s translation of Meian second hand. He was discouraged no one had talked to him about it, but glad the novel would receive renewed attention. He didn’t know that John had written about him in his memoir. I read him the passage. He was grateful, and spoke of John’s tremendous talent. “I’m sure John did a wonderful job,” he said. “If he’d talked to me, I might have had something to contribute. I would have been glad to.” We talked about the possibility that John’s translation might supplant his, by virtue of the built-in, academic readership Columbia attracts. “Maybe it will lead to a kind of Soseki renaissance,” he said. “I’ve had a good life, but I’d love a few more years. I’d like to be around for that.”

Dreux Richard is KJ’s In Translation Editor. He resides in New Zealand.