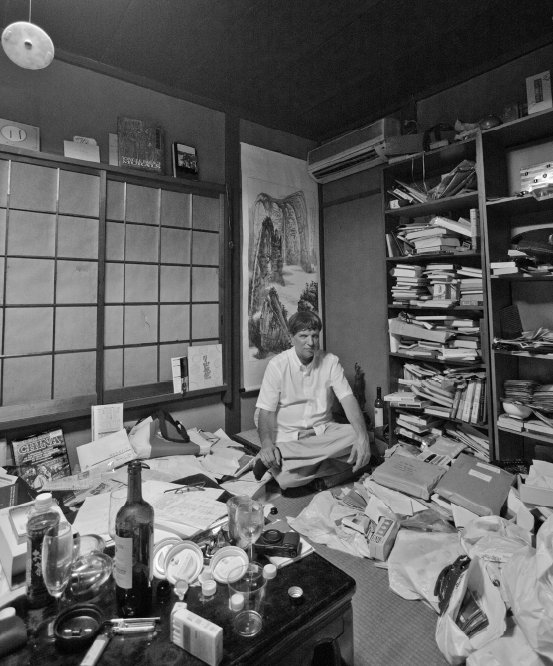

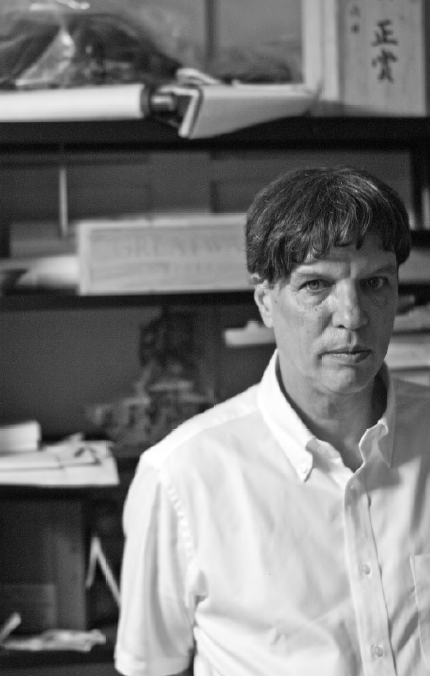

I OFTEN MET WITH LEVY HIDEO (in my family, we still call him Ian) in his 21st floor office overlooking the Kanda River at the university in Tokyo where he teaches. The office, like his home, is overflowing with discarded paper coffee cups, cigarette butts, and food wrappers. A thin film of coffee grounds and cigarette ash covers nearly every flat surface. Levy has little time to devote to cleaning. The first and only westerner to gain critical recognition as a literary writer in the Japanese language, he is a literary celebrity in Japan, and like any Japanese author his acclaim is predicated on a furious rate of publication. The fifteen books he’s written in the last twenty years are scant few by Japanese standards.

Recently, his best writing has been inspired by travel to rural China, where a former Peoples Air Force private chauffeurs him through rural Henan Province in search of cultural authenticity, which he finds increasingly elusive in 21st-century Japan. Agricultural China, a crossroads of poverty and tradition, appeals to Ian’s notion of culture as a delicate alchemy endangered by globalization. “My life story is a battle with modernization I know I’m going to lose,” he told me. Coming from an American-born author responsible for destabilizing the ethnic essence of Japan’s national literature, his perspective is rich with irony – in literary discourse (as in Japan at large), modernization and westernization are often held equivalent.

I had been in Japan two weeks when I met with him the second time. It seemed natural that we would talk about my father. They had met as college students at Princeton and remained close friends until Ian left America permanently in 1990, choosing not to stay in touch with anyone after he left. Our conversations were his first chances to hear about one of his former friends since. He was curious to know how my father had spoken of him, and it became clear that, like any man who has effected his own disappearance, Ian was deeply invested in discovering how he had been remembered. After our meeting he walked me to the elevator.

“So your dad really told you to find me?” he asked.

“Of course,” I said, and boarded the elevator by myself.

“And he’s glad he met me?”

“You were friends. Remember?” The doors closed. As the elevator descended, I puzzled over Ian’s questions— there had never been a falling out between Ian and my father, nor controversy of any kind.

Over the coming year I would learn Ian had excised the life he’d once lived in English from his consciousness, triumphs and friendships along with it. “I’ve largely been able to live out my own dream,” he later told my father. “I had imagined this fantasy version of Japan when I was in New Jersey, and when I came here I did everything I could to make it real.” The fantasy, of course, was a world in which Ian had written award-winning literary fiction in Japanese. When his debut novel (Seijoki no kikoenai heya, reviewed in this issue) won the Noma Prize in 1992, fantasy became reality and replaced the less satisfying life that had driven him to dreaming.

In public, I soon found out, Ian had begun pretending he could no longer speak his native language with ease. He’d spoken in America only once since leaving Japan, delivering a lecture at Stanford which he began by apologizing for his lapsed English. He titled the lecture The World in Japanese. His recent essay of the same title recounts his translingual journey and argues that the use of the Japanese language is a culturally and historically reconstructive act in which Japanese identity is encoded. Clearly, he believes his emigration from English is more than merely lingual.

For Ian, 2011 was spent in confrontation with the language and life he had left behind. His fiction was translated into English for the first time. His mother died suddenly and he traveled back to Washington, DC, where he’d partly grown up, to bury her. Unsettled by the willful amnesia I’d encountered at the end of our second meeting, I convinced my father to visit Ian in Tokyo; it would be the first time in twenty years Ian had spent time with a friend from his former life. At the end of July when I spoke to him for the last time before leaving Japan, recollections of his mentor, the author and translator John Nathan, emerged anew from beneath the transformation he’d willed on himself; it was rare nostalgia for a life he’d always been desperate to abandon. Twenty years after departing, he returned, however briefly, to the world in English. I first discovered Ian’s linguistic peculiarities after he invited me to audit his advanced seminar in literature and translation. It became predictable: at the end of each class I approached him with questions I needed answered in English, often about the timing of my father’s visit, and he would panic, nervously asking one of his students, whose English was rudimentary, to translate. The late Masao Miyoshi, who made his literary career in America, was known to behave similarly, pretending he had forgotten how to speak Japanese. In praise of Ian’s debut novel, Ōe Kenzaburo had perceptively compared the two authors.

To understand Ian’s habits of speech as mere affectation, however, is to ignore how frequently and willingly he articulates a candid self-awareness about them, often in the classroom. A born educator, he shares a deep rapport with his students and teaches with encompassing magnanimity, leaving little room for pretension. “I only speak English in public when I’m paid to, and you can’t afford me,” he sometimes remarked to our class. His invitation to join the seminar, offered in spite of my regrettable Japanese ability, belied his claim that, as a matter of policy, he does everything he can to keep English out of his life, as did the conspiratorial grins he wore whenever I forced him to speak English in front of his students. But he was also fond of recalling a boast his late father used to make about him: “He would say, ‘my son is speaking English, but he’s really thinking in Japanese and translating himself.’ My father was good that way. He understood.” That understanding may have died with his father. What Ian really believes about his relationship with English is complicated and his explanations —often the subject of his brilliant, well-rehearsed answers to interviewers’ questions—are colored by a lifetime of vulnerability and contradiction.

His fiction reflects his ambivalence. Much is autobiographical, including Seijoki no kikoenai heya, his only work thus far translated into English. In Seijoki, a fictionalization of his early encounters with Japanese language and culture, teenage protagonist Ben Isaac flees the US Consulate in Yokohama where his father is installed and wanders the night streets of Shinjuku in search of comprehension. Confronted with a mirror in a Japanese friend’s apartment building, Ben is surprised to find a Caucasian face staring back. “Since running away from home, Ben made every effort not to look at mirrors,” Levy wrote. Of the novel’s translation into English, Levy explained, “It’s a mirror too many, almost. One reflects the light into the other and you get this overwhelming glare.”

In May, Levy’s students skipped class to watch him deliver a public lecture on the Man’yoshu. The hall where he spoke seats 1100. He sold it out. Hours before the general-admission event began, attendees crowded several floors of stairway leading to the hall, hoping for a good seat. For a writer whose earliest work was met with accusations of fraud (critics insisted he was passing a Japanese writer’s work off as his own), such expressions of public support are doubtless sweet vindication.

The Man’yoshu, a collection of Japan’s earliest imperial court poems, is largely the province of literary historians. Ironically, as the sole contemporary novelist who is also a Manyo’shu scholar (his translation won the National Book Award in 1982), Ian has benefitted from a nationalistic surge in Man’yoshu interest. His lecture held the crowd of mostly senior citizens in thrall. He played wittily to their potential prejudices, conjuring an admittedly absurd image of himself as a young American in 1970s New Jersey attempting to determine how best to praise the Japanese emperor in English. Early in the lecture, and for the third time since I met him, he pretended he had momentarily forgotten the English translation of the word akogare (roughly, ‘yearning’). The audience nodded credulously as he wrote the word in English on the blackboard behind him, where it remained after he left the stage, a reminder.

MY FATHER VISITED IN THE SUMMER, a few days after the English translation of Ian’s novel had been published. They met at a shrine in Ian’s neighborhood and were instantly surprised to find each other’s voices the same as they remembered. From the shrine we walked to a family restaurant, where they disclosed the grief they might have helped each other weather. Both had lost their parents. My father described his mother and father dying within a year of each other, including details he had never disclosed to me: how his father’s blood transfusions had slowly reached a point of diminishing returns and my father had decided to halt them, consigning my grandfather to deepening dementia and a gradual, wasting death; my grandmother, I learned, had died in the arms of a man she’d gone outside the marriage with. Ian recounted the details fo his mother’s sudden passing a few months earlier. He recalled returning to Washington, DC to make arrangements; his mother had raised him in the shadow of the capital, but he’d long since disinherited DC in favor of identifying himself (whenever his American origin couldn’t be avoided) with the literary vibrancy of 1960s Manhattan, a place he had sometimes wandered, but never lived. It was early Friday evening; the restaurant had filled with noisy teens and twenty-somethings on their way to Shinjuku’s nightlife. Ian and my father had to speak over the din.

The next night, before dinner, Ian gave us a tour of his house. It was built in the traditional Japanese style in 1963—ancient history for Tokyo architecture—and is an extension of the identity Ian has cultivated. On the verge of being overtaken by bamboo growth, it sits at the end of an unpaved alley on a plot where, according to rumor, the house depicted in Natsume Soseki’s Mon once stood. As we began the tour, Ian related the elements of the novel he found most meaningful: Mon tells the story of a young couple living in a house shrouded from daylight by an adjacent cliff. In the darkness, the husband gradually forgets how to read kanji, beginning with the kin of ‘kindai’ (roughly, the modernity in ‘modern’).

Ian took us up to the anteroom adjoining his on the second floor, one of two rooms he’d recently had professionally cleaned. Honors, awards and distinctions from his career as a man of Japanese letters occupied several bookcases. He took great joy in enumerating these to my father, reserving special affection for mementos he’d acquired during his visits to the imperial palace as a guest of the Empress, herself a poet and an avid reader of his work.

It was six o’clock when we arrived at the nearby restaurant that keeps its private corner booth reserved for Ian. We remained until half-past midnight, well after closing time. For my father, still jetlagged, it was a marathon, however welcome. For Ian, who engaged in the only unselfconscious use of English I ever witnessed from him, it was pure invigoration. He ensured the evening carried on by continuously ordering food and drinks “to clear our palates.” Much of it remained on the table at the evening’s end.

Having already shared the wounds the years had wrought the night before, the two of them spoke as friends do, not as friends long lost. My father was most interested in discussing recent trips he’d taken to Russia; he was once fluent, and had hoped his career— spent in the Department of Justice working on national security issues during the Cold War—would someday return him to St. Petersburg, where he had lived his most cherished years. Ian’s chosen recollections displayed the full evolution of his transcultural consciousness. He had spent much of his childhood with his father, a career diplomat in Asia, and recalled the boyish brinksmanship of slipping across the border into Communist China. “It was Shenzhen. I remember there were ducks walking through the village,” he said. “Now it’s this incredibly sleazy city of millions. It represents the Hong Kong-ization of China.” Ian also reflected on the bizarre fame afforded literary writers in Japan, recalling the year that, unbeknownst to him, his writing was featured on the admissions test for one of Japan’s most prestigious universities. He was invited to speak at Japan’s top cram school. “There were so many students, more than the building could hold—they were pouring into the street. It was like I was Mick Jagger,” he said.

Ian had forgotten a trip he and my father took to my family’s lakeside cabin in the Pocono Mountains of Pennsylvania. My father, who recalled the trip fondly, was astonished that Ian couldn’t remember, and described it at length, but to no avail. My father had forgotten about a party at Harvard Law he’d invited Ian to. One of my father’s law school classmates had asked Ian his vocation. When Ian responded that he was an expert in East Asian studies, my father’s classmate had quipped, “What’ll you do with that? Open a laundromat?” Minutes later, Ian had thought of a comeback. He’s hung onto it ever since. “I should’ve said, ‘I’ll be sure not to launder any stuffed shirts,’ but you never think of it in time,” he told us.

Both vividly remembered traveling to Washington, DC in their undergraduate years to attend anti-war protests; my father had since donated the placards they carried to the Smithsonian, having discovered them in his childhood home after his mother’s death. During the protests they had stayed with Ian’s mother, a conservative Republican, at the Arlington home where Ian had come of age. She had hosted them, my father had often recalled, with both kindness and a clenched jaw.

That night at dinner with my father and I, Ian spoke of his years with his mother in Arlington with simultaneous affection and aversion. In life, as in his novel, Ian’s father was among the many East Asian diplomats who left their American wives to marry East Asian women. In Seijoki, Ben Isaac experiences his mother’s subsequent victimhood with a kind of eerie, creeping wonder: “Left alone in the living room, Ben could almost smell her silent torment clinging to the lace curtains like smoky incense.”

“You know, I wish she’d lived long enough to see me do more. More recognition.” Ian said at dinner. “For the longest time, I never cared about awards. I started late.” His novels have won three prestigious awards, but the most politicized honors (including the Akutagawa prize, for which he has been nominated) have eluded him. It was already near midnight, and Ian’s regret seemed to leave my father at a loss. It felt right to fill the sudden silence with a description, for my father’s benefit, of the Man’yoshu lecture Ian had given: of the enormous crowd, held rapt for an hour and a half by Ian’s wit and insight, filling the vertiginous hall with laughter and applause.

“I wish you could have been there,” Ian said to my father. “You know, after my mother died, that lecture brought me back into the world.” He leaned back in the booth and gazed upward. “I wasn’t sure I could still do it. It was great, though. It went really well.” His eyes seemed to focus on something beyond the ceiling. “One thing I always wanted – to really get a shot at the Nobel Prize. And she would find out.” His stature in the Japanese literary community certainly justified his grandiosity, but I wondered if it had occurred to him that, historically, East Asian writers have received Nobel consideration based primarily on the English translations of their work.

AFTER MY FATHER’S VISIT, Ian found his voice in English. My American girlfriend accompanied me to a dinner he held for his students the next week, and though he initially greeted her in the broken, Japanized English he often reverts to when forced to speak his native language in public, he shortly thereafter engaged her in a steady stream of English conversation. He punctuated every exchange with expressions of disbelief at how freely he was using his native language. All of this shocked the student seated next to us, whose parents had been lifelong friends of Ian’s, and who, in the two and a half decades he had known Ian, had never heard him speak English at length. Ian also eagerly agreed to an English language profile to appear in Kyoto Journal, and discussed with great excitement the upcoming American book tour Columbia University Press (which had published the translation of his novel) was planning for him.

At the end of the night he assigned me an in-class presentation on Natsume Soseki’s Kokoro, one of the first Japanese novels he’d read in his youth. It was unusual to ask an auditing student to present to the class, and he acknowledged with halfheartedly feigned frustration that I likely wouldn’t be able to deliver the entire presentation in Japanese.

The table fell silent for a moment. “You’re kidding, right?” one of his students asked, voicing his peers’ collective incredulity.

Ian assured them he was in earnest. After a silent moment in which they worked to overcome their disbelief, they began to applaud. Startled, Ian searched the room for some other object of approval before raising his hands in protest.

When I gave my Kokoro presentation, which I had labored to prepare much of in Japanese, he began class by asking who would translate the English language portions. The class erupted in laughter, and he seemed relieved by their reaction, as if he had been given a kind of permission; he translated me with characteristically amused chagrin. When I finished, he singled out one sentence from the hand-out I’d distributed, and praised it. “This is a beautiful sentence,” he said, and read it aloud to the class: “The past has become the present, and in the future’s possibility lurk the ghosts of what’s already been lost.” He lowered his voice and read it again, this time metrically. He drew a breath as if to speak. “Huh,” he said, nodding. A moment passed.

“That’s beautiful English,” he said twice, addressing the class first in Japanese, then in translation.

WE CONDUCTED OUR FINAL INTERVIEW in Ian’s home library, a few days before I left Japan. He sat in front of a rubbing taken from a stone monument erected during the construction of a synagogue in Kaifeng over eight hundred years ago. In Ian’s novel Henrii Takeshi Rewuittsukii no natsu no kikou, the title character travels to Kaifeng hoping to come into contact with proof of the city’s long vanished Jewish community. The novel concludes as the protagonist, having discovered what was once the synagogue’s well in the boiler room of a dilapidated hospital, sets off down a street lined with crude construction sites, feeling suddenly unburdened. Children emerge from nearby houses and shout the only English words they know: “What is your name?” Unable to answer, the protagonist breaks into a sudden sprint, wherein the novel concludes. Ian’s copy of the monument, a prized possession, is one of two in Japan. “It reminds me that people have always translated themselves. It’s a reminder that there was a bilingual consciousness at the beginning of literary history.” Precedents like these allow Ian to believe his accomplishments speak to a significant, evolving element of the human search for identity and purpose. Without them, what remains is ego, and the profoundness of his will.

His recent interest in China is a kind of homecoming. He spent five years in Taiwan as a child, learning and speaking Chinese, but never desiring fluency in a foreign language until he first encountered Japanese at age fifteen, when his Western identity had already formed. “Chinese never became a literary language for me,” he said. “It was mere culture.”

Writing about China in Japanese is an intriguing reversal and a fitting second act for an author whose debut novel effected a reconceptualization of the relationships between Japanese ethnicity, language, and literature. In traveling to China, where he is still able to communicate in his childhood language remarkably well, and writing about his trips in Japanese, he is consciously perturbing centuries of literary tradition, in which travels to China were documented in kambun and Japanese script was proprietarily reserved for literature about Japan. His recent work aspires to disambiguate the Japanese homeland from its written language in much the same way his earlier efforts called into question the largely ethnic notion of Japan’s ‘national literature.’

When he finished telling about China, I asked Ian why he had stopped translating when he began writing his own novels. He confessed he had never been asked that question and explained that, under intense pressure to accomplish the impossible feat of writing Japanese literature in his koutenteki (acquired) third language, he had come to view translation and creation as mutually antagonistic. In that regard, he had only one regret: not having taken the opportunity to complete a major translation of Nakagami Kenji, the beloved burakumin author who first publicly encouraged Levy to attempt literary writing in Japanese, and whose passing, Levy and other critics believe, closed the book on modern Japanese fiction’s era of relevance. Ian’s hereditary association with Nakagami, who is broadly canonized, provides him with a critical bulwark against the shallow pathologizing and cultural narcissism that his literary accomplishments often inspire. The few American writers who have addressed Levy’s career have focused almost exclusively on the how of his accomplishments, rendering his story in the disturbingly familiar context of American exceptionalism. The comparatively overwhelming attention in Japan is almost always concerned—at times obsessed—with the why.

“When the Japanese press interviews me, it’s always about inferiority or exclusivity. Either they ask what made me crazy enough to try writing in Japanese, or they want to know why I find the Japanese language particularly beautiful, and it becomes one of these instances of nationalism.”

“There’s really no way—no didactic way—to answer that question of why you did it,” I said.

“You have no idea. It’s such a relief to hear you say that.”

It didn’t seem right to explain that I’d only meant to clarify.

Later in the interview I brought up his years at Princeton, when he and my father were closest, and this led us to discussing John Nathan, Ian’s professor and mentor, whose translation of A Personal Matter was crucial to Oe Kenzaburo winning the 1994 Nobel Prize for literature. To Ian, 21 years old when he met Nathan, whose success as a translator was at its height, the elder scholar had been a paragon of linguistic ability.

Until I met John Nathan,” he said, “I thought I was the only gaijin who could speak authentic Japanese. He was beyond fluent, beyond perfection.” Levy had remained at Princeton for his graduate work, turning down an offer from Harvard, in order to study under Nathan.

He recalled the moment when the seed that would later bloom in his Japanese novels was first planted: while Ian was at Princeton, Oe was sending copies of his novels to John Nathan, and Ian caught sight of an inscription Oe had written on an inside cover that read, “As the translator I trust the most, I look forward to John Nathan writing his own original literature.”

“I was extremely inspired by that,” Ian said. “John Nathan was never the kind of person who would have tried to write in Japanese, or even to believe he was capable of it. But to me that inscription proved something.”

“When Nakagami told you to write your own Japanese literature, it must have been like a thunderclap,” I said.

“Wow. Yeah. Wow,” he said. “I guess—absolutely. I hadn’t thought.” For a minute, he was quiet, lost in thought and memory. “The last twenty years of my life have been a denial of that whole period,” he admitted.

On a bookshelf directly behind him sat Nathan’s collection of Yukio Mishima novels, borrowed in the 1970s and never returned. Ian had been referring to Nathan in the past tense, as he tends to refer to whomever and whatever he left behind in America, though Nathan is alive and well, and still teaches. “I haven’t thought about this in a long time,” Ian said. “It’s really moving to think about now.” He seemed to be thinking aloud, both relieved and puzzled by the vastness of what he was remembering. The interview had run nearly five hours, most of it addressed to the fraught parts of his past no Japanese interviewer or American academic had ever thought to ask about. He was misty-eyed and hoarse. “Wow,” he concluded. “What a mentor.”

I reached John Nathan by phone shortly after returning to America. Ian’s recollections of how Nathan perceived himself turned out to be accurate. “First of all, I’d say Ian was entirely wrong about me,” Nathan said. “I was a very technical user of Japanese, but I could never have written in the language at a literary level.” Nathan recalled Ian as the most vulnerable and driven student he had ever taught, a wide-eyed, wonderstruck innocent who would nonetheless frequently proclaim his intent to surpass his mentor. “He would say ‘mukou wo haru’—I will surpass you,” Nathan said. “And he has surpassed me, which is great.” I’ve since told Ian how to contact Nathan, but knowing his former mentor is only a phone call away won’t likely lead to any reunions. Though he overcame the barrier of language during my time in Japan, he overcame neither the time nor distance that had accumulated along that barrier—my father and I had to do that for him.

As that final interview concluded I thought to mention something I’d learned in the course of my reporting: Ian’s name had surfaced in Nobel Prize discussions. It had been a difficult rumor to confirm, and I was proud of the reporting I’d dedicated to it. But it seemed wrong to mention it then, when it would have disturbed his reverie and recollection, decades overdue. Too, the whole truth could have been heartbreaking to hear. Ian’s accomplishments had indeed been mentioned in Nobel circles, but Japanese authors are given deliberate Nobel consideration perhaps once a quarter century and the prospect of granting candidacy to an author who isn’t ethnically Japanese is politically complicated. Even prohibitive.

Before he walked me back to the train station and we parted for the last time, I photographed Ian in his home, for this article. He was exhausted and had to fend off sleep whenever I photographed him sitting down. He nonetheless insisted on seeing the pictures I’d taken and pointing out which ones he preferred. He suggested multiple locations throughout the house, and the shoot dragged on, despite his exhaustion. If we managed a shot he was particularly fond of, it seemed to jolt him awake, and he would insist on taking more from that angle. What at first seemed like mere vanity became definite and recognizable as he pointed out what he liked about each photo. He saw how the light had struck him, how the walls had framed his face. He saw how it made him look when he posed in front of a ragged shoji, surrounded by the garbage-strewn chaos of his office, and gazed steadily at the camera, presenting a portrait of calm intent that belied the frenzied, eccentric genius he intended the room to advertise. Better than anyone ever will, he saw the things about himself he wanted other people to see.

Dreux Richard is an American writer, journalist

and literary translator. He covered Japan’s African community for The Japan Times during his time in the country, and continues to serves as Kyoto Journal’s In Translation editor from New Zealand.