Takenishi Hiroko, born in Hiroshima in 1929, made her name as a perceptive critic of premodern Japanese literature before she began writing fiction. She has engaged in a broad range of literary activity over the years: editing, criticism, fiction, the translation of premodern works into contemporary Japanese, and has won many awards, both for her fiction and for her literary criticism.

Takenishi is a survivor of the bombing of Hiroshima and much of her fiction centers on that horror, which happened when she was a sixteen-year-old high school girl living 2.5 kilometers from ground zero. Her best-known Hiroshima piece is perhaps The Rite (Gishiki), a gripping story of a despairing A-bomb survivor whose most serious wounds are psychological.

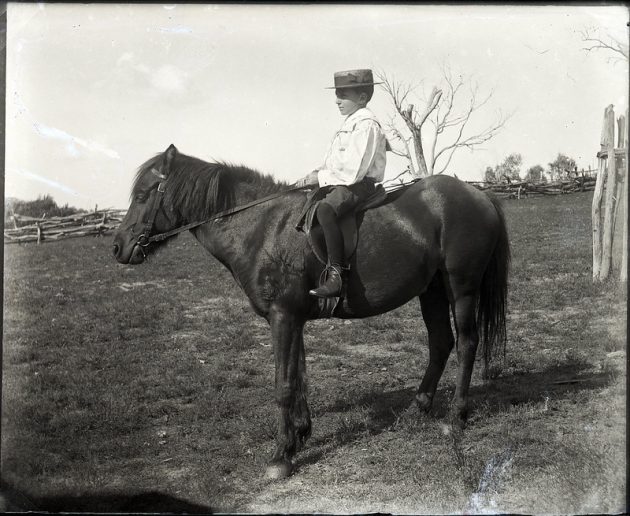

On the surface the placid Troopers’ Inn (Heitaiyado), centered on the young boy Hisashi and his love of horses, would seem to have little in common with The Rite, either topically or in narrative style, but a reader familiar with the author’s background as an A-bomb survivor will certainly read a sense of foreboding into the tranquil home front setting.

Takenishi’s straightforward prose in Troopers’ Inn offered no extraordinary translation problems. There was, of course, the task of attempting to express differences of formality in dialogue, for example the conversation between Hisashi’s mother and the maid near the beginning of the piece. Later, in dialogue between the mother and an officer-lodger, both sides use elevated respect language. This requires the omission of contractions in the English and resort to the occasional “I shall” and the like, creating a stilted exchange which more or less reflects the tone of the original dialogue, though this translator had nothing special in his bag of tricks when the mother referred to her son as honnin, “the person in question.”

Troopers’ Inn, only the second Takenishi short story published in English, was published in the journal Umi in 1980 and was awarded the Kawabata Yasunari Literary Prize the following year. It is, in fact, one of nine Takenishi short stories in which young Hisashi is the central character.

The boy Hisashi was drawing a picture of horses. He was drawing three military mounts galloping together, seen from the side.

It was Sunday, but someone had come from the factory and a little while ago his father had left as soon as he had finished breakfast. Before he left the house his father had handed him a quarter sheet of drawing paper and told him it was the day’s allotment.

Hisashi’s study looked out on the garden at the back of the house where the Madagascar periwinkles bloomed, so he could hear everything his mother and the maid, an older woman who lived in the house, said as they hung out the laundry. He couldn’t see the place where they usually hung up the laundry from his room, but today their ex-lodgers’ futons and sheets had taken over that area, so his mother and the maid had strung a line between two oak trees and were hanging up the yukatas worn by those who had stayed with them.

“I wonder,” the maid said, “if the officers are already on the troopship.”

“They might be on board, but I’d guess it’s still in the harbor. I don’t think it’s that easy to set off,” his mother replied.

“When it’s hot like this and the sun is shining right down on you out on the ocean, young or not, I’ll bet some get seasick.”

“Every day with only the sky and the sea to look at. And it’s not as though they’re on their way home to parents awaiting their return or they’re taking some kind of pleasure cruise. When you think about it like that, we can’t complain about having to put them up for the few days before they board ship.”

“Well,” the maid began, “one or two nights wouldn’t be a problem, but a week is too long, even if we don’t have to provide their meals.”

“They tell us it’s the times we live in, that His Majesty is asking us to do it, but to have the soldiers using the front room for so many days, you know….but when you think of where they’re going, I suppose it’s only human to want to let them sleep in the biggest room, the room with the alcove. It passes if we’re patient for a bit. Anyway, we don’t know what the weather will be like tonight. Besides, something might happen that will keep them from boarding their ship.”

“I wonder if there are homes that refuse and say they can’t let soldiers stay.”

“I don’t really know. If someone were sick I suppose it would be a definite problem, regardless of what your assignment of soldiers might be.”

The maid patted the collar of a dry yukata between her hands to take out the wrinkles. There was a note of disapproval in her voice.

“You know how the head of the neighborhood association comes and tells us we have lots of rooms and sets our quota with that expression on his face that says it’s only natural we take responsibility for housing them. That really gets under my skin. I’d like to ask him if he thinks we’re delighted to have to billet so many.”

“Look at it from his position,” Hisashi’s mother responded. “I doubt he’s telling us that simply because he wants to.”

“I understand that, but if a lot of people in our neighborhood assume that responsibility, in the end, doesn’t it make him look good?”

“I don’t really think there’s much we can do when the inns are full and they’re asking families near the harbor to put the military up, you know.”

“Ma’am, I think you and the master are a little too good-hearted. It’s ‘yes, yes,’ all the time. That also sets my teeth on edge. When I put myself in the place of those waiting for a ship, I feel just like you, ma’am. What I’m trying to say has to do with the association head. Sometimes it would be good to give him more of a hard time.”

This week Hisashi had been sleeping between his mother and father in the room with the Buddhist altar, which also served as the passageway to the storehouse at the back of the house; this was an arrangement that Hisashi enjoyed. Whenever they changed the rooms they slept in, he felt as though he were on a trip with his parents. In two years he would be taking the examination for middle school.

The head of neighborhood association had notified them that whenever military waiting to be shipped out were assigned lodging in their home, they need not concern themselves with the men’s meals or bathing; they need only provide a room to sleep in and bedclothes. People in the association had undertaken this billeting and called such houses “troopers’ inns.”

At Hisashi’s house they had billeted soldiers a number of times, sometimes for just one night and sometimes, as in this latest instance, soldiers stayed for as long as a week; occasionally enlisted men were included, but for the most part they were officers, and no more than five of them at a time.

At Hisashi’s house there was an old man who had come for years to do light clean-up in the garden and straighten up things around the outside of the building. A young woman who had come for training in etiquette had gone back home to take care of a sick parent, so the live-in maid was quite busy.

The maid hated it when soldiers were billeted in the house: she had more laundry to do and the house smelled of combat boots. Summer was good for drying laundry, but when there were five pairs of boots lined up on the concrete floor at the entryway, there could be no doubting the pungent odor.

Hisashi’s mother did not really know what criteria the head of the association used when deciding on the number of soldiers to be assigned to each house. But in terms of the number of rooms, there were houses that were given no allotment even though they could easily take in soldiers. The association head had made a point of telling Hisashi’s mother that this time he had reduced the allotment of soldiers for her; she felt no particular gratitude at this.

Just as the association head had said, Hisashi’s house did not have to provide any meals or bathing to the men quartered there. But given her nature, Hisashi’s mother treated the men to generous amounts of tea and sweets. She could not let herself do otherwise. Some officers would only drink tea, and did so without saying a word. Other officers would accept nothing and refused to touch the sweets, saying that they couldn’t allow themselves to impose on her. And there were also officers who took what was offered, ate the sweets with obvious delight, and asked for more tea. Hisashi’s mother was clearly moved by what she saw, no matter the reaction she encountered to her hospitality.

Shortly after the government started quartering soldiers in their home, Hisashi’s mother made mugwort rice-cakes at home. On that occasion they had enlisted men in the house in addition to officers. The onset of billeting didn’t mean more work for Hisashi, so he was quite pleased by this turn of events.

It had been the custom at Hisashi’s house ever since he could remember that people would always come from the factory to help pound the rice for New Year’s rice cakes. They had built a brick oven in the backyard. When they steamed the glutinous rice in a steamer basket and emptied it in the mortar, two high-spirited men would stand facing each other, ready and waiting to begin swinging their wooden mallets to the rhythm of their own chanting, alternating their swings under the winter sky. The steam rising from the mortar would envelop the men’s faces. Turning the rice was the maid’s task.

Hisashi, working with his mother’s fed firewood into the oven as the December wind blew and they choked on the smoke. He would run to the Shinto and Buddhist family altars, bringing the steamed rice as offerings. He would eat, getting a single dollop of the hot, gooey rice served in his rice bowl with a wooden rice scoop and talk awkwardly with people from the factory. He would be busy and exhausted at day’s end, but happily so. The saké they drank for purification would put the men in a jolly mood; he could smell it on their breath as they swung their mallets.

Only on this day was a covering spread out on the wide verandah and in Hisashi’s study, which abutted it. This area became an improvised workshop for the manufacture of mirror rice-cakes. Hisashi’s mother and a young woman helper would put the newly-pounded rice in a wooden box, immediately sprinkle rice-flour on it and their hands, and as they squeezed out a morsel with one hand, with the other they would quickly tear off the piece and shape it into a small round cake.

More than once his mother had shown him how to do it, but Hisashi’s way of tearing off and shaping a cake was overly cautious, which meant that the cake would cool on him, unhappily making his cakes more clay than rice. And when the rice clinging to his fingertips and hands hardened, it was next to impossible to return his hands to their pristine state without soaking them in hot water.

For this mochi-pounding now, however, they could not get as many people to help as they might like, and Hisashi’s father decided to simplify matters, aware of how things were in Japan, where people had begun to exercise self-restraint in all things. His father asked the man who worked around the house to make a device at the side of the house using a stone mortar and one mallet, a mallet operated not by hand, but one that rose up when it was stepped on and automatically dropped to strike the center of the mortar when the foot was removed. With this device the rice could be pounded without the aid of men.

They had already changed over to the stone mortar by the time the lodging of soldiers began. The maid stepped on the mallet, Hisashi’s mother shifted the mound of rice about, Hisashi darted around, and the mugwort rice-cakes got done. The maid was quite pleased with herself and said she might even read a book as she pounded the rice, just like Sontoku Ninomiya, the Edo era paragon of diligence and frugality who never wasted a minute. The mugwort was fresh, so the rice-cakes were fragrant indeed.

That time, however, they were unable to give the rice-cakes to the soldiers. The officer didn’t touch them, so his men could only do likewise.

“We are grateful for your thoughtfulness,” a soldier said to Hisashi’s mother as he stood at attention in the entryway and saluted before hurriedly running off after the officer.

The maid, fuming, was at the sink washing dishes and talking to herself.

“That fool officer! Why didn’t he let his men eat? We made a special effort for them! An officer who can’t feel for his men can’t be a decent leader!”

She went on vilifying the officer. Hisashi’s mother sensed the maid’s complaints were on the mark. She began to think that the officer had not even considered their feelings, let alone what his men felt, but then she reconsidered. No, she decided, she couldn’t expect it to not have been a trial for him as well. How much easier it would have been to have given the rice-cakes to his men. Putting it in that light, she felt sorry for the officer as well, not just his men.

The officers who left Hisashi’s house this morning looked to his mother to be still young men in their twenties. While they were staying at the house their grooms, leading their mounts, would come for them early every morning. The three officers would set off on their horses and return to the sound of hooves. The head of the neighborhood association had said he thought there was a military post not too far away.

Every morning Hisashi had gone out front to see the mounted officers off. The summer vacation proved to be a lucky time for him. Hisashi’s father never encountered the military men who stayed at the house. The task of meeting their needs fell mostly to his mother and the maid. The officers were generally men of few words, but nonetheless it was Hisashi whom they talked with the most.

In Hisashi’s eyes it was obvious which horses the several officers would ride. The tallest officer’s horse was the best looking. The second finest horse was ridden by the heavy officer. That the short, thin officer was assigned a mount that neatly matched his physique amused Hisashi, but he thought it only right this horse was the one with the best coat.

The tall officer had offered to draw his Japanese sword from the leather case at his waist and show it to him. Hisashi, however, shook his head. He was more interested in horses than swords.

People often say that a horse has good eyesight all out of proportion to its size, yet Hisashi wondered why horses had such gentle eyes. Looking at an eye, he would often forget that it was a horse’s eye. And the movement of the fore and hind legs never failed to astonish him, no matter how long he gazed at them. In the complexity of the motion was an invisible something that transcended mere strangeness, a something that had made such a living creature, and this frightened Hisashi. He could only think it magnificent.

Hisashi would often get down on all fours on the tatami — once he was sure no one was around — and try to walk like a horse. But all too soon, within seconds, he would topple over and land on his back. He fell again and again, but would get up and try yet again. If he thought someone was watching him pretending to be a horse, he found himself a bit embarrassed, and lay there on his back, laughing at himself, belly up, his arms and legs flapping in the air like a May beetle’s.

That he could see three horses up close every day animated him. Whenever they had free drawing at school he always drew horses. His drawing teacher would praise his pictures, saying his horses were alive, unlike those that the others in the class might draw. Once the teacher, without saying a word to Hisashi, entered his horses in a exhibition of elementary school drawings sponsored by a newspaper and the drawing won first prize. He was happy enough to have won, but he felt no special attachment to the prize. To Hisashi it was the horses that mattered, not the prize.

A friend asked Hisashi to draw a picture for the friend’s homework project. He wanted Hisashi to make a kind of draft, because they would both be in trouble if the teacher saw through the scheme. The friend said he would finish it. Hisashi had doubtless drawn many horses for this friend. He never once felt, however, that he was drawing it for someone. He was seized by the desire only to somehow capture the profound gentleness of the horse’s eyes and the astounding motion of its legs. The more he drew the more it seemed to him that the eyes of actual horses grew increasingly gentler and that the motion of their legs were all the more magnificent. He felt that by drawing he was getting closer to the animal, yet at the same time it also seemed to him to be growing more distant; whenever he drew a horse he savored the surprise and joy he had felt the very first time he had done so. And the unease he had felt also came to him anew.

There was a particular reason why his father gave him only a single quarter sheet of drawing paper every day. His father had told him to make good use of the paper. Yet even though Hisashi’s father in his heart of hearts saw promise in his son’s becoming enthusiastic about drawing — done every day simply for the love of it, unrelated to any schoolwork — he thought the boy was becoming thoroughly engrossed in it and losing all sense of time, and perhaps threatening his health. He concluded that if it were just one drawing, there would be a limit to the time Hisashi spent on it, thus the boy and his father came to an agreement that he would not waste paper and he would get a single sheet.

And the idea had also occurred to Hisashi’s father that, paradoxically, it would be better for the boy’s drawing if he was always left with the desire to have at least one more sheet of paper. Although his mother got him all his school supplies, the drawing paper alone was under his father’s control. Hisashi decided this was because it had nothing to do with school.

Hisashi thought his father was more than a little stingy: there was so much drawing paper in the drawers in his father’s Japanese-style desk! The desk was the size of a tatami mat and the three drawers at each end were all locked.

One drawer contained papers from the factory that were apparently important. Another drawer had such things as ear picks, tweezers (regular and small), and magnifying glasses. There were all sorts of magnifying glasses, two and three-lens glasses piled one on the other in a jumble. The same drawer held several fountain pens made overseas. His father had a habit every morning before getting up of making an entry in a diary for the previous day. The pens he used were all foreign-made.

In the other drawer that Hisashi knew about was a fat album in which were pasted foreign stamps and several college notebooks, plus lots of as-yet-unsorted foreign stamps wrapped up in cellophane. Hisashi guessed his father had ordered these stamps from somewhere and that they came on a regular basis.

On his day off Hisashi’s father often called him over to the desk.

“Want to see a new stamp?” he would ask.

Hisashi would lean forward.

“Let me see.”

His father, handling them very carefully, would lay out his newly-acquired stamps on a sheet of white paper, one by one, with a pair of small tweezers. Some had postmarks, some did not. He would not go into any particularly elaborate explanation.

“This one is quite rare, you know,” he might say, or, “Don’t you think the color’s nice?”

He sometimes urged his son to take a good look at the design with a magnifying glass.

At home he never wore Western clothes, and even when he went out he customarily wore Japanese clothes except for very unusual circumstances. Hisashi found comfort in the fact that this same man would take pleasure in collecting foreign stamps one by precious one.

This is what his father told him shortly after he entered elementary school; he remembered it even now.

“If, unavoidably, there’s a time when you have to walk in the dark, you must clench your fists and walk along hiding your face with your elbows. Because, you know, it’s vital that you anticipate the enemy outside and protect your eyes from danger.”

When it came to getting concrete advice from his father, this was about the extent of it; he recalled nothing else.

The quarter-sheet drawing paper was in the bottom drawer on the left-hand side of the desk. Hisashi didn’t know, however, what was in the remaining two drawers. For him, the big desk with its locked drawers and their unknowable contents was just like his father.

It had happened three nights earlier.

The officers, who had returned on their mounts, were taking a short break in the parlor. The tall officer, speaking for all three men, made a request of Hisashi’s mother.

“We apologize for imposing on you for such a long while. In a few days we shall have to depart. But before we leave we should like to take Hisashi with us when we make a shrine pilgrimage. We shall take full responsibility so that nothing untoward happens to him. Please leave Hisashi in our care all day tomorrow.”

The shrine they were going to visit was one Hisashi had been to a number of times on school outings when he had been in the lower grades; in the spring a great many people from all over came together on the grounds of the shrine to see the cherry trees blooming. There was also a river nearby.

“Thank you very much. I am sure he will be delighted,” Hisashi’s mother said as she withdrew. “When my husband comes home I shall discuss it with him and give you our formal reply.”

When Hisashi was asked about the outing and saw himself with the horses the whole day, he almost danced with joy. Of course he would go! Unable to contain himself, he addressed the officers directly.

“You’re going on horses tomorrow too, aren’t you?”

The tall officer’s answer was a disappointing one.

“Tomorrow we go by train.”

Yet even the heart of a child had to sense, if only dimly, the fate of the officers after they left the town, so Hisashi also felt that it would not be right for him to refuse to refuse to go. At the same time, however, he also felt this outing to the shrine was a bother. They weren’t from the area, so they were doubtless curious about it. As for the possibility of cherry blossoms, the trees were all leaves now. They would have to be careful lest caterpillars drop on them from the leaves and branches. But yes, he’d go. That he decided. If his father said it was okay to go, he’d be their guide.

It was after nine the next morning when Hisashi received a canteen of chilled barley tea from his mother and left the house with the officers. His mother bowed deeply to the men.

“Please look after the boy.”

Hisashi was thankful that the officers had little to say, either on the train or walking along the street. Hisashi felt uncomfortable if he ran into the maid as he was coming home from school and she from shopping. She would pepper him with questions he was expected to answer.

“How did it go today?”

“Did you eat all your lunch?”

“You have a lot of homework?”

Or she might say: “I hear someone from the factory is coming over this evening. You want to bathe before dinner? Or would after dinner be better?”

Hisashi was somehow embarrassed when he was with people and a family member called out to him. And not only that. A thought would inevitably present itself.

Are we going to walk or talk? Let’s do one or the other!

He felt that way both with the young woman who had helped around the house and with his mother.

The officers were not walking especially fast, but because their stride was long, Hisashi had to walk at a brisk pace to keep up. Irrespective of their height, the three men were in step with one another, causing Hisashi to marvel at their training. When they would come upon soldiers along the way, the soldiers would likewise pick up the officers’ step and salute them. In return, white gloves moved smartly to their cap visors. Just walking with them almost made Hisashi dizzy.

A broad view of the river opened before them as they came to the approach to the shrine. There were no horses in the river.

“A cavalry troop that’s finished its exercises on the drill field often goes into the river, but it’s still early today, so there aren’t any,” Hisashi said, the expression on his face almost apologetic. Seeing a column of cavalry men near dusk work the reins and lead their horses quietly down the sloping river embankment and into the flame-colored river for a brief rest, each swaying figure one with its mount, was a sight Hisashi never tired of, no matter how often he saw it. The instant the movement of man and horse ceased, Hisashi saw before him a magnificent procession of ancient haniwa figurines.

The four of them rested a while on the now horseless riverbank.

Hisashi told the officers that he came to the nearby drill grounds with his friends to fly model airplanes and explained in detail just where and how the cavalry horses that had ended their maneuvers would come to the riverbank.

“You must really like horses,” said the tall officer. “Because they’re so smart, right?”

“How smart are they?” the boy asked.

The heavy-set officer responded.

“Sometimes they’re smarter than people.”

The thin officer only smiled. Then, as though talking to himself, he spoke.

“They can’t speak, but they can talk with their bodies, and they’ve no trouble reading a human’s mind.”

The cherry trees on the shrine grounds were in full leaf.

Hisashi often noticed invalided soldiers from the Army hospital who had been given permission for outings here, attired in their white hospital robes and military boots, sitting on benches with people, presumably family who had come to visit them, but because it was morning there were no such visitors yet either. Hisashi found that he was relieved by their absence. It was a sense of relief that he certainly had not anticipated coming here.

The three officers removed their caps and bowed their heads toward the inner shrine for a good while. Hisashi, behind them, took his cue from this and likewise bowed his head. There was a cemetery for those who had been killed in action at the back of the shrine. Hisashi fretted; he wanted to spirit the officers off the shrine grounds before they noticed the cemetery. There was only a scattering of visitors to the shrine.

It was already evening by the time Hisashi returned home, his face tanned by the sun. He carried under his arm what appeared to his mother to be a book of drawings of military steeds.

“Thank you very much,” the tall officer said to Hisashi’s mother. “We have brought Hisashi safely back to you.”

Hisashi’s mother asked him what they had done that day, but he didn’t go into much detail. Only that after they had visited the shrine they had taken a suburban train. And that after they had had a meal when they got back into town, they had gone into the biggest bookstore there, and that the officers had bought him the book of drawings, even though he had certainly not pestered them to do so.

Hisashi had not talked with the men about anything particularly noteworthy, yet he was aware that his feelings toward them were completely different from what they had been before he left the house that day. His belief that the outing was a bother had disappeared before he knew it. His report to his mother was a bit dispirited.

“Are you glad you went?” his mother asked.

He nodded, yet it was not an especially enthusiastic nod.

That morning, after the officers had left, Hisashi entered the study and was absorbed again in drawing the three horses. He had no desire to draw horses that were simply standing. He was determined to have galloping the three horses that had met the three men every morning. They had to be galloping. With their tails, not just their manes, flying behind them.

A month later a letter, together with a single photo, arrived addressed to Hisashi’s father and signed by the three officers. The language was spare and straight-forward, and thanked the family for looking after them during their stay. It said the men were attending to their duties in good health. They wished the family every happiness.

The photo, taken in front of the shrine’s cherry trees in full leaf, showed Hisashi in the center with the tall officer leaning over behind him, his hands on the boy’s shoulders. The heavy-set officer was to Hisashi’s right, his white-gloved hands on the haft of his sword. The thin officer stood to Hisashi’s left. For some reason he was whimsically looking skyward and away from the camera.

There was no return address on the back of the envelope, only the name of the unit to which a letter might be sent. On the front had been stamped the phrase Passed by censor. Hisashi, as he considered the meaning the departure of the three officers had had for him alone in the family, realized within the unfocussed sorrow that quite suddenly surrounded him that he had most certainly stepped now into the realm of a new emotion, one heretofore foreign to him. Unable to tell either his father or his mother, he contemplated this thought for some time.

From issue KJ69, published March 10, 2008

Lawrence Rogers teaches Japanese language and literature at the University of Hawai’i at Hilo. His translations have appeared in the New Directions anthologies, The Theepenny Review, Zyzzyva, and other journals. His book, Tokyo Stories: A Literary Stroll, University of California Press, won the 2004 translation award from the Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture at Columbia University

Images sourced from Flickr and Pinterest.