Awa Naoko: Timeless Tales

Awa Naoko (1943-1993) was an award-winning writer of modern fairy tales. She was born in Tokyo and while growing up lived in different parts of Japan. As a child, Awa read fairy tales by Grimm, Andersen, and Wilhelm Hauff, as well as The Arabian Nights, which later influenced her writing. She earned a bachelor’s degree in Japanese literature Japan Women’s University, where she studied under Yamamuro Shizuka (1906-2000), who translated Nordic children’s literature into Japanese. While still in college, Awa made her literary debut in the magazine Mejiro jido bungaku (Mejiro Children’s Literature).

Hanamame no nieru made (Kaiseisha, 1993) collects six of Awa’s stories about Sayo, a twelve-year-old girl who lives with her grandmother, the owner of a hot spring inn. The title story “While the Beans Are Cooking,” which originally appeared in Kaizoku (Pirates) in 1991, won the second Hirosuke Dôwa Prize. In it, grandmother tells Sayo how her father met her mother, the daughter of a yamanba (mountain witch). Readers familiar with the works of Miyazawa Kenji (1896-1933) may recall his Matasaburo the Wind Imp, as the wind plays an important role in both books.

Awa’s timeless lyrical prose still resonates with readers today. Many who grew up with her stories now share them with their children. Once a year, Awa’s friends and fans gather and discuss her works over tea and cookies at her alma mater. Hanamame no kai, an association named after Awa’s 1993 book, was started in 1993 to preserve her literary legacy for future generations. I hope my translation will play a role in introducing new readers to Awa. I would like to thank Mr. Minegishi Akira, who has granted me permission to translate his late wife’s work.

Sayo didn’t have a mother.

Not long after Sayo was born, her mother had gone back to her village—a place with beautiful plum blossoms beyond many mountains. But no one—not even Sayo’s father—could visit the village.

“It’s a Yamanba village,” Sayo’s grandmother said. “Your mother is the daughter of a Yamanba, so she went home to the Yamanba village. Nothing could be done about it.”

The Yamanba is a mountain witch. Mountain witches and humans are very different creatures.

‘How did my parents get together if they were so different?’ Sayo wondered. ‘Why did they separate after they got married?’ Every time she thought about it, she felt empty and alone.

‘When it rains in my village, does it rain in the Yamanba village? When hydrangeas are in bloom in my village, are they in bloom in the Yamanba village?’ Sayo wondered.

It had been raining since the morning, and there was nothing to do. Sayo told Grandmother, “I want to visit the Yamanba village.”

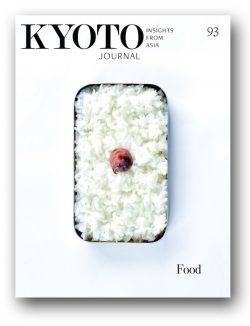

Grandmother was cooking kidney beans in a big pot. Sayo’s father had gone to Kitaura to buy groceries. Takara Hot Springs had no guests. The hot spring inn deep in the mountains was soaked in rain and silence.

Grandmother lifted the pot lid and sprinkled sugar on the beans swelling inside. She said, “Nobody can go to the Yamanba village. Your father can’t go. You can’t go either, Sayo. Neither can I.”

“Then how did Father meet Mother?” Sayo asked.

“Well, that was when…” Grandmother reduced the fire cooking the beans and looked at Sayo. “I’ll tell you the story of how your father met your mother if you like. But it’s going to be a long story.”

Sayo nodded. “I’ll listen to your story, Grandmother, while the beans are cooking.” She sat on the wooden floor, hugging her knees.

As a young girl, Sayo would listen to Grandmother’s stories while sitting on the kitchen floor—stories of tanuki badgers, of bears, of long-nosed tengu, and occasionally of Sayo’s mother. Sayo didn’t think Grandmother’s stories were completely true. They were half facts, half stories.

The aroma of the big purple beans filled the spacious kitchen. They were harvested from the garden in the backyard of Sayo’s house. The side dish of sweet beans cooked in the big pot had become a specialty at Takara Hot Springs.

Grandmother nodded a few times. She placed the wooden lid on the pot and sat next to Sayo. Then Grandmother began her story.

“It was a long time ago, many years before you were born, Sayo. There was no road leading into the mountains, and no bus came to Takara Hot Springs. Your father and I managed this hot spring inn all by ourselves. It was a small, small inn, you see. Now the village women come to help us, and your father can travel by car to buy things for the inn. But back then he had to walk narrow trails with groceries on his back. Even so, your father was very strong and could easily carry heavy loads. Well, he hiked over Mitsumori Ridge, beyond Warabi Mountain, and went to Kitaura to buy fish and seaweeds. He brought back a mountain of beans on his back.”

“Beans? We could’ve grown a ton of beans in our garden, Grandmother.”

“No, Sayo. We didn’t have a garden back then. Your father bought beans in Kitaura, and I cooked them for our guests here. The beans from Kitaura were so delicious. When I cooked soybeans, red beans, and kidney beans, they became wonderful feasts. Many guests swore they’d never forget my beans. They would come back two or three times just to have them again.

“So your father would carry groceries on his back when he came back from Kitaura. His rucksack was so heavy that he would have to rest once in a while. About halfway up in Warabi Mountain, he would sit on a rock. He would smoke and mop his brow before he would set out again. But once, while your father was smoking his pipe on the rock, somebody called his name—’Sankichi, Sankichi.'”

“‘Sankichi, Sankichi’? Who was it?” Sayo felt excited. Sometimes she heard a voice calling her name in the mountains. Whenever someone called her, Sayo would answer yes. Then she would skip and run, waving at trees, wind, and clouds.

Sankichi, Sayo’s father, also answered when someone called his name. Then a breeze blew and shook the dry leaves off the trees. When Sankichi looked up, he saw a fox sitting on a fallen leaf and smoking a pipe.

“What have we here? A fox?” Sankichi laughed. Then he blew a puff of smoke and stood up. The fox also blew smoke from his pipe and got up.

‘What, is he mocking me?’ Sankichi wondered as he tossed his rucksack over his shoulder.

Then the fox said, “Could you give me some beans?”

Sankichi ignored the fox and adjusted his rucksack on his back. He began walking. The fox followed him.

“May I have some beans? May I have some beans?”

Annoyed, Sankichi turned and stared at the fox. “What do you want beans for? Foxes don’t eat beans, do they?”

“I’m getting married tomorrow,” the fox said.

“Hmmm.” Sankichi stopped and turned back. “Do foxes cook red bean rice for their weddings, too?”

The fox nodded. “Yes, we do. We make lots of it and every fox in the mountains eats it.”

Sankichi was delighted for the fox. “That’s great. You’re getting a bride.”

“Yes. Sankichi, don’t you have a wife yet?” the fox asked.

“No, not yet.”

“In that case I’ll pray that you’ll find a good bride. All of us foxes in the mountains will pray for you. One prayer for each red bean you give us.”

Sankichi didn’t have the heart to say no. He put his rucksack down, took out a bag of red beans, and handed it to the fox. He thought it was too much, but he decided to be generous for the happy occasion. Delighted, the fox held the bag of red beans tight and disappeared into the dry trees.

After this incident, Sankichi would often hear someone call his name in Warabi Mountain.

“Sankichi, Sankichi.”

When he looked up, he saw hundreds of shrikes perched on a large dry tree.

“Give us soybeans. Give us soybeans,” the shrikes chirped.

“No, I’ve got no soybeans!” Sankichi cried and began to run. Then the shrikes flew up, scattering across the sky like black sesame seeds. They kept trilling: “Soybeans! Soybeans!”

The fox and the shrikes were not the only ones who wanted what Sankichi carried in his rucksack. A weasel pestered him, following him around, whenever he bought dried fish. Just before New Year’s, an ogre chased after him, wanting his black beans. As always, Sankichi heard someone call his name. When he turned around, he found a big ogre in leather clothes staring at him. Horrified, Sankichi tried to run away. Then the ogre said in an unexpectedly quiet voice, “I don’t want them for free. I’ll trade you one gō of gingko berries for one gō of black beans.”

‘What should I do?’ Sankichi thought.

“Then how about two gō of gingko berries for one gō of black beans?”

Sankichi said nothing.

“Then how about three gō of gingko berries for one gō of black beans?” The ogre kept offering more gingko berries for Sankichi’s black beans.

Sankichi tried not to laugh. He waited until the ogre offered five gō of gingko berries. The he shouted, “All right. I’ll trade you one gō of black beans for five gō of gingko berries!” Then he put his rucksack down, scooped black beans up in his hands, and put them into the ogre’s leather satchel hanging from his shoulder. Then the ogre grabbed gingko berries with his large hands, about five gō, and put them into Sankichi’s rucksack.

“Good, good. Now we’re ready for New Year’s Day,” the ogre said, his large eyes shining with joy.

“Do ogres cook black beans on New Year’s Day, too?” he asked, closing his rucksack.

The ogre nodded. “I have just taken a bride, and she makes excellent black bean dishes,” he said, a big smile on his face.

“Hmmm. Even you’re married now.” Sankichi was very impressed.

“Yes. My wife is an excellent cook.” The ogre gave a big nod. His leather satchel bouncing on his back, he strode down Kumazasa Hill.

‘I wish I had a wife,’ Sankichi thought as he watched the ogre go away. Then he remembered what the fox had once told him.

The fox said all the foxes in the mountains would pray that Sankichi would find a good bride. He also said they would say one prayer for every red bean Sankichi gave him. “Some charm that was,” Sankichi muttered, shrugging.

In fact, the fox’s charm seemed to have worked.

Some time later, when the plum trees blossomed in Takara Hot Springs, Sankichi heard someone call his name on a mountain path: “Sankichi. Sankichi.”

Unlike before, this was a woman’s voice, a voice as soft as a spring breeze. When Sankichi heard the voice, he felt as if flowers were blossoming inside of his chest.

He turned around, but no one was there. He stopped and waited for a while, but no one appeared. This happened a few times. Then one day, he heard the voice again.

“Sankichi. Sankichi.”

As soon as the soft voice reached his ear, he smelled plum blossoms in the air. Feeling a breeze tickle the back of his neck, he turned and found a girl dressed in a red kimono. There was a touch of red on her eyelids. She reminded Sankichi of a plum flower about to blossom.

Surprised, Sankichi remained silent.

“May I have some kidney beans?” she said, smiling.

“Kidney beans,” Sankichi repeated, taking his rucksack off his back. He scooped the large beans into his hands and gave them to the girl.

“Please put them in my sleeve,” said the girl.

Sankichi gently dropped them into the sleeve of her kimono. Then she held her sleeve and shook it with the beans inside. She opened it and looked inside. “Oh, beautiful,” she said. She came close to Sankichi and whispered, “Why don’t you look inside my sleeve?”

At first Sankichi hesitated. When he finally looked inside her sleeve, he saw a small garden overflowing with kidney beans. As far as his eye could see, the field was filled with purple flowers in full bloom, their silk-like petals swinging in the wind.

“What in the world…” Sankichi was amazed.

“Let’s make a garden like this,” the girl whispered into Sankichi’s ear.

She held the sleeve of her kimono and shook it. The beans rattled the way they did before. When she opened her sleeve, there were the red kidney beans inside, as if nothing had happened. The girl leapt up like a child and said, “Thank you.” Then she began to run. As she ran along the path lined with dried trees, she shouted, “My mother will be delighted!” The girl went away, her long hair waving behind her. Her voice still lingered in the air after she was gone.

“My mother will be delighted!”

The wind carried the fragrance of plum blossoms. The girl’s voice hovered in the air, and the spirit of spring seemed to be running around and laughing.

Sankichi remained standing there for a long while. She must be a wind spirit, he thought. She didn’t appear to be an ordinary human at all.

“This is the story of how your father met your mother, Sayo. But this story doesn’t end here.” Grandmother rose, lifted the pot lid, and checked the beans. She picked one, ate it, and added some more sugar. Then she sat in front of Sayo.

“My mother’s mother ate the beans my father gave them, didn’t she?” Sayo asked, her voice excited.

“Yes. Your mother’s mother was a Yamanba. And she loved kidney beans. When she ate them, she would be in such a good mood that she would do anything for us. That spring she sent us a lot of fuki buds, mountain udo, other gifts.”

“Who brought them here?”

“Well, even now I don’t know for sure. It may have been the fox, or the weasel, or the ogre. At dawn, the door of the hot spring inn shook, and I heard a strange voice: ‘Delivery from Mrs. Yamanba!’

“I jumped up, ran through the hallway, and went down to the hot spring inn. When I opened the door, I found a large bamboo basket filled with gifts from the mountains. We’d given her only one gō of kidney beans. I thought she gave us too much.

“I asked Sankichi, ‘Is it okay to accept all these?’ He laughed and said, ‘We’ll just give her more beans next time.’ That’s right, I thought. I decided to cook beans with sugar this time. I dragged a big pot out of the cellar and cooked lots of kidney beans. While cooking, I thought it was a good idea to make friends with the Yamanba. Because she’s the guardian of the mountains. I put my kidney beans in a nest of boxes and sent Sankichi with it.”

“Did the Yamanba like it?”

“Yes, she did. She was so happy that she gave Sankichi her only daughter.”

“Ah, she’s my mother, isn’t she?”

“Yes, she’s your mother, Sayo. I was so surprised. Sankichi went to the mountain and came back with a beautiful girl in the evening of the same day.”

“Did you know Father was going to marry her?”

“Yes, I did. Because Sankichi looked so happy. But I was a bit worried. I wondered if the daughter of a Yamanba would be happy living among humans.” Grandmother’s face became clouded.

That night, when Sankichi told her he wanted to marry the girl, Grandmother didn’t know what to do. The girl was beautiful, polite, and kind. Besides, she was a hard worker. But the girl was the daughter of a Yamanba. Grandmother couldn’t sleep that night, thinking that the girl would go back to the mountains some day.

After thinking all night, Grandmother still didn’t have a solution. “I don’t know what to do,” she sighed. Just as dawn began to break, the front door of the hot spring inn shook, and Grandmother heard a loud voice. “Delivery from Mrs. Yamanba!”

Grandmother sprang up and ran along the hallway. When she opened the door, she was amazed at what she saw.

Outside the doorway there was a heap of belongings—three large boxes, a brand-new quilt, a wardrobe covered with arabesque print cloth. At first glance, she realized it was a bridal trousseau.

Grandmother crouched down on the ground and realized that nothing could be done. Now it was too late to send the Yamanba’s daughter back to the mountains. She dreaded offending the Yamanba.

Grandmother remained there for a while, deep in thought. Then she made up her mind. She got up and shouted in the direction of the mountains. “I accept your daughter! I promise I’ll make her happy!”

Suddenly, a spring breeze came up and swayed trees in the mountains. The tree buds shone like stars.

“That’s how a beautiful bride came to our house. She was a hard worker, she worked very hard at the inn and at home. She even planted kidney beans in the backyard. In her garden, purple flowers blossomed, and we harvested a lot of beans. They were bigger, shined brighter, and tasted better than ones from Kitaura. Your mother’s beans became the treasure of Takara Hot Springs. Then she gave us another treasure. She gave birth to a beautiful baby girl. That was you, Sayo.”

Sayo just nodded.

“We were so happy when you were born. So was the Yamanba. She sent us more gifts.”

Sayo nodded again.

When Sayo was born, the Yamanba sent a cradle woven of Akebi vine and freshly pounded rice cakes. The rice cakes were round and white, and there were fifty of them. Grandmother shared them with guests at the hot spring inn.

“The Yamanba’s rice cakes were so delicious. Sankichi, your father, gobbled seven of them down. Your mother and I ate a lot of them, too. But she stopped talking after she ate the rice cakes. She stopped working and began to spend her days staring toward the mountains.

“I wondered what was wrong with her. I feared she had become homesick. Your mother hadn’t gone home, not even once, since she came to Takara Hot Springs three years earlier. That’s not good, the Yamanba must miss her daughter very much, I thought. So I told your mother, ‘Why don’t you go visit the Yamanba once in a while?’

“Your mother nodded and ate five rice cakes in silence. Then she disappeared at dusk. After the nightfall, Sankichi and I looked for her everywhere, but she was nowhere to be found. A few days passed, but she didn’t come home.

“Later I learned that someone saw a woman run across the suspension bridge in the twilight, spreading out her arms like wings. Her red sleeves flapping in the wind, she shouted, ‘I’m going to be the wind. I’m going to be the mountain wind.’ Then her voice turned into the sound of wind. After she disappeared, there was still a whistling sound in the air.”

Sayo felt a pang of sadness. “Then…did Mother really become the wind?” she murmured.

Grandmother nodded. “Yes, your mother indeed became the wind, Sayo. She went home to the Yamanba and became the mountain wind. Sometimes she would come down to our village to rock your cradle. Then you would smile. The wind must have been calling your name—’Sayo. Sayo.'”

Sayo nodded. The wind still calls my name, she thought. Whenever she walked through the mountains, she heard the wind call her name.

“And? What happened to the Yamanba’s gifts? Did she stop sending us chestnuts and bamboo shoots?”

“Yes. I haven’t heard from the Yamanba for a long time. But she’s still there. She lives somewhere in the mountains and watches over Takara Hot Springs. Your mother comes here as wind and always watches over you, Sayo.”

Sayo nodded and looked out the window. The misty rain kept falling, and the faraway mountains were tinged with purple.

“Well, the beans are done.”

Grandmother got up.

“They’re ready. A minute more and they’d be overcooked.”

Grandmother removed the pot from the fire, lifted the lid, and scooped some beans inside. Then she put them on a small plate for Sayo.

As she nibbled the freshly cooked beans, Sayo thought about the Yamanba village beyond many mountains and about her mother who became the wind.