Interview by Kathy Arlene Sokol

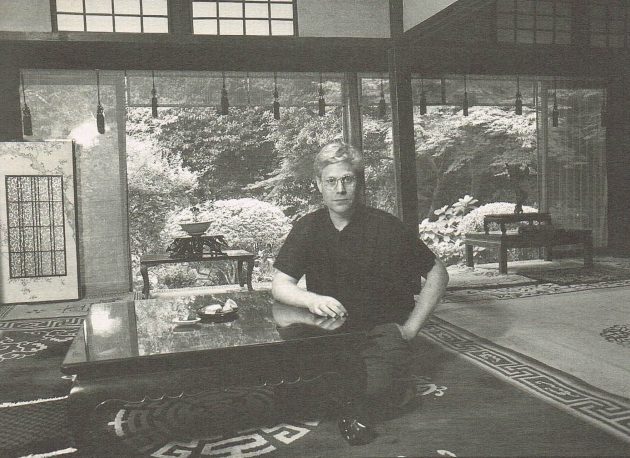

Alex Kerr first glimpsed Japan as a child of twelve in 1964. Awed by the culture’s aesthetic appreciation of the ephemeral; the harmonious interplay of shadow and light; and the seeming timelessness of tradition, he felt sensually at home. After graduating summa cum laude in Japanese studies from Yale, he went on to study Chinese as a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, finally settling in Japan in 1977. He immersed himself in the traditional arts—kabuki, Noh, tea, and calligraphy—and became connoisseur of aware, the poignancy of transient beauty. Attempting to evade the prosaic, he often sequestered himself in Iya Valley on the island of Shikoku. But even this hidden recess was not sheltered from the onslaught of modernization. The Construction Ministry soon dispatched its legions to subdue hillsides and discipline its streams with the vast grey death of concrete. No longer able to narrow his focus to the culture’s exquisite but imperiled details, he sat down to write of his sense of loss and the overwhelming triumph of the modern. His musings resulted in an award-winning book ironically embraced by an equally disturbed Japanese public. From his office in Nichibunken, the International Center for Japanese Studies, he spoke of his deep concern for his adopted country’s future and his bittersweet memories of her best, brightest and darkest moments.

Kyoto Journal: Originally written in Japanese, the book entitled Utsukushikii Nippon no Zanzo (English: Lost Japan) won the Shinchei Gakugei Literature Prize for nonfiction; you being the first foreigner to receive that prize. As it is a somewhat critical appraisal of contemporary Japan, do you think that if a Japanese had written the very same book, he or she would have been awarded for it?

Alex Kerr: I think it’s unlikely. This book is really about traditional culture and about the natural environment. I think that when people write about these subjects there is a tendency to think about them as a traditionalist. So a Japanese might have been written off as, “oh, it’s another tea master grumbling about days past.” Whereas a foreigner writing about these issues gives people the sense of freshness; this is an outside view. It’s by a foreigner, therefore presumably someone modern, up-to-date. If I say it, it doesn’t have that traditional cast about it.

Do you prefer writing in Japanese or in English?

Actually I write so much in Japanese these days, I’m not sure if I can tell the difference. The interesting thing is that whichever one I’m writing in, it’s very difficult to translate. It took me almost two years to translate this book which came out first in Japanese three years ago. It was very difficult because our point of view about these things is different. The Japanese version is a more of a stream of consciousness approach whereas in English as an English writer you somehow feel that you have to be more rational: there has to be an ‘a’ and a ‘b’ and therefore a ‘c’. Also there are a lot of cultural issues that the Japanese know very well but might have to be explained to a foreign audience. So, the translation process has been tremendous.

The book implies that the loss of culture in Japan was somewhat willful and the Japanese in their attempt at swift modernization could probably have done things differently. Can you articulate what are some of your deepest concerns for this country?

Well, willful…the idea that they could have done it differently… I mean, when you look back at history how can you say anything could have been done differently? And this is a matter of history. One of the fascinating aspects is that it isn’t only a Japan problem, it’s an all-Asia problem. The problem is that modernization, which includes the Industrial Revolution and modern education, etc., came to these countries with precipitous speed.

When I was studying at Oxford in England there was a library I used to go to in Merton College; at 700 years old, it’s the world’s oldest. When you go in there it looks pretty much like a modern library. I mean, there are little touches like the books are chained to the walls but I suppose we’ll end up doing that pretty soon. So, history may repeat itself. But the way the chairs and tables are, the concept of a library and of ordering books in a certain way, we’ve had that for 700 years.

Here, in Japan, if you look at the way a studio of an old literati would be arranged or the sutra room of a temple with things wrapped up in brocade, it’s a wildly different concept—no relation. So, suddenly you have something like a library coming in and then everything else—hospitals, schools, everything that makes up modern life. Completely no connection with the old tradition, which makes them feel that the old tradition is irrelevant. Now, it isn’t really—there are fantastic, beautiful and I think valuable things in all the Asian traditions. But for people for whom this has happened in 10 or 20 or 50 years instead of 700, it’s very difficult to keep these things together in their own minds. And so the damage that we’re seeing in Japan, is just a precursor of what we’re now going to see in China and in Thailand and in Vietnam and all through Asia. And so that’s one reason why I think what’s happening in Japan is very significant. It’s something to learn from.

You still haven’t quite told us what you think that damage is.

Oh, the wholesale ravaging of the environment. For example, in Japan, rivers are concreted over from start to finish. There are only two rivers in the whole country that have not yet been dammed. There are 320 or 330 dams already in operation and the construction ministry is planning to build 330 more at a time when European and American countries have already decided not to build any dams at all if possible because of their known damage to the environment. You drive through the countryside and mountains are typically blown up and the entire surface is covered with cement. Something like 60 percent of the entire seashore is lined with huge concrete tetrapods which are sort of four-pronged concrete pieces that keep the seashore from eroding. And it’s not that erosion is worse in Japan than it is in other countries or that there were not alternatives. It’s that a mindset that got stuck, say, forty or fifty years ago, was never revisited. They never went back and said, “well, maybe, there is another way to do this.” And part of the mindset is that natural surfaces that have been flattened and paved over are considered modern. They’re a step forward. The attitude is that that is advance.

So, environmental damage continually goes on. Over half of the native forest of Japan, has been decimated, completely deforested and replanted with commercial cedar which lowers the water table. This country for its size and the percentage that happens to be mountainous forest has probably the world’s lowest level of wildlife – you can’t find birds, you can’t find animals and the reason you can’t find them is that they can’t live in these forests of cryptomeria pine which are a kind of ecological desert. These pines give off a pollen that has caused a national epidemic of allergy. And all for what purpose? Again, there was an idea right after the war and in the early 50s, that this was going to bring money to forest people; that the forest villagers would be able to work by raising the trees and then cutting them down. Well, there are no more forest village people, these villages are totally depopulated. Nobody wants to do that backbreaking work and they don’t need to. This is a very, very wealthy country. People don’t need to work in those forests and Japan doesn’t need that as an industry. In short, for an industry that contributes less than l percent to the GNP, they’ve wiped out their ecology. When you reach this stage where for such tiny economic benefits you’re able to wreak such drastic damage to the environment, that is an imbalance which is severe. And that means that you have a country that is in trouble.

We’re on the subject of environment, but let’s ask ourselves what’s happened to those mountains? What were those mountains? Well, Japanese culture was the culture of autumn grasses, the culture of maple leaves, the culture of cherry blossoms. Everything that was Japanese culture was what those mountains were. And by wiping those out, they wipe out the very base of what it was all about, from a cultural point of view as well.

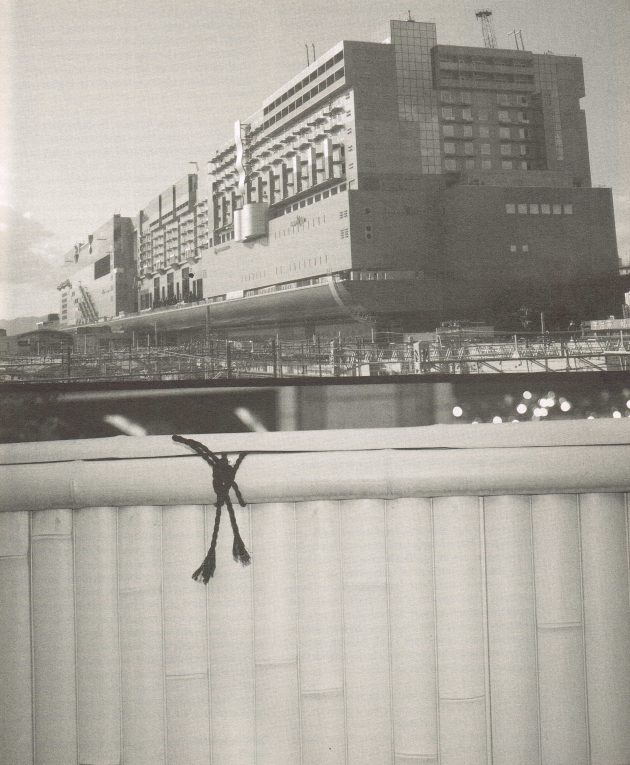

Then you look at their cities. You look at Europe there are hundreds of ancient, beautiful old cities that have been lovingly preserved. Many of them made of wood. You can drive a little bit outside of Oxford, for example, through the Cotswolds to Stratford-on-Avon and for hours on end it’s village after village of gorgeous thatch-roofed old wooden houses all of which have been preserved. In Japan, there is no such thing anywhere as a completely preserved city let alone village. There is not a single city in the whole country that is not cement and flashing lights, overhead telephone wires and pachinko parlors – absolutely hideous concrete blocks and shiny plastic and tile everywhere. So, a country that has created this much ugliness both in its countryside and in its cities, is a country that I think has a lot to worry about.

The late Alan Booth in his book Looking for the Lost called what has happened to the Japanese countryside, state-sponsored vandalism. But do you think that this is all due to the intractability of the Japanese bureaucratic system or should the Japanese people themselves, the citizenry, take some responsibility and try to rectify this situation?

Well, of course. Actually there are two things going on. As I said earlier, there is an attitude or a point of view toward these things. I call it the “build and pave ethos” — that building man-made objects of any type whether it’s an office block, or a bridge, or a concrete embankment, that that is glamorous and modern. That’s a mindset that stuck back in the 50s when Japan was still poor and was desperately trying to recover from the war. But, you know, we’re not in the 50s. We’re now the richest country in the world and it’s time for that mindset to change. So, yes, I don’t know if I would call it responsibility, but certainly until that mindset changes, nothing will happen.

Now, the bureaucracy is another question because it also happens to be true that Japan really is ruled by its bureaucrats and they really do have autocratic power and unfortunately, your typical citizen or even citizen’s group has almost no recourse. And so part of Japan’s modern tragedy is, in fact, that that attitude of “build and pave” HAS changed to a great degree. There are millions of people out there who are very unhappy. I found that out after I wrote my book. People started writing me letters. I got bags of mail from people saying, “finally, you have said it.” But, of course, people feel helpless because the bureaucracies are indeed all powerful in a way that’s very difficult for people to imagine outside of Japan.

In particular, the construction industry which is at the root of much of the damage in the countryside, is a subject in and of itself which I write about in my next book. But suffice it to say, that the money that flows from construction projects is the money that supports the political system, it’s the money that supports most mountain villages today and most seashore villages are supported by essentially a kind of government handout which doesn’t come in the form of cash, it comes in the form of civil engineering works which keep the people busy working all year long building roads and concrete embankments. Without it they all would be out of work. So, construction has become for Japan a kind of addiction, it’s like a drug which the country is addicted to and it’s very difficult to get off it because their economy is now dependent on it. Another aspect is that the construction industry here is nearly double the relative size of that in other developed countries in the world. That is to say, the number of workers, the GNP devoted to it, the money spent per citizen, that sort of thing, is double. Well, when that is so, that means to cut back on construction could practically cause a depression from an economic point of view because they are so dependent upon it as an industry. Japan is now addicted to this which is why I think change is going to be very difficult. Japan has a case of what I call “drug addiction.”

Change, you write, must take place, but who is to take on the responsibility of creating that change. When you look at the young generation and their seeming non-connection with things past, or with traditional values or any other kind of cultural inheritance, what role do you see them playing in a revolution? Will they play a role?

In order for things to change, a revolution of a sort must take place but I am not at all sure that will happen in Japan. Part of the problem in Japan is that in some ways it’s very comfortable. Japan needn’t really do anything and could go right on as it is and no one would notice. So, there’s no tremendous push for revolution except by some people who are unhappy at seeing the mountains being ravaged or maybe they feel that the cities are ugly but what kind of strength does a feeling like that…as the Japanese would say, a mere ‘kimochi’…. what bearing does that have when the economy and the bureaucracy and the political system are going along quite nicely, thank you. So, I’m not sure there will be a revolution.

I’m really talking about a situation that I see and I can’t honestly imagine how they’re going to get out of. I think it’s that difficult here. I’m more concerned that people learn in other countries, especially other Asian countries, how to face these issues as they’re now beginning… places like Burma, Vietnam and Thailand are now at the stage where Japan was in 1950.

As for the young people, that’s a double-edged sword. The educational system has turned the young people into children. They’re taught in school to do what they’re told to do; they’re very well behaved. But many of them are incapable of taking one step outside of what they are told to do. So, that’s a big worry to me. On the other hand, there is one advantage to the younger generation not having any base in the culture and that is…Japan’s culture, if you don’t come at it with any preconception, if you come at it completely fresh, if you land off the boat from America you will fall in love. It has an absolutely invincible beauty of its own. But it’s the older generation Japanese who associate their traditional culture with being cold and poor and dirty and old-fashioned and all of that stuff. They can’t just see their culture for what it is, they associate it with those things and therefore they have very mixed feelings. They can’t wait to get rid of it and be free of it and so on. The younger generation, they are foreigners like us. They might as well be Americans off the boat and that means that they can more easily fall in love with it. And I have young Japanese come out and visit me at my house and they love it. They’re perfectly happy out there in a way that their parents, who actually know more about these things, could never be.

But I think you’re talking about a very specific kind of young person. I don’t know if the typical high school graduate is capable of appreciating the kind of aesthetic lifestyle that you enjoy.

It’s a matter of what they’re introduced to. As it stands, of course, the educational system and everything else will never teach them about these things and they’ll continue to grow up and to live in horrible plastic and concrete cities. They’ll never see this lifestyle unless they happen to be introduced to it. So, that’s the other side of this. I’m not sure how many of them will ever know that these things exist. When they see them, I find people who have no prior interest in any of these things – your typical kid that’s gone to high school, who will follow the track, who is going to take the examinations, go into university, go into a company….put them in the right setting and they’ll fall for it just like we do because it is irresistible if you come at it without all that background.

But with the continued eradication of this kind of lifestyle, it’s going to become virtually impossible to be exposed to these ideas, these values.

That’s exactly Japan’s modern dilemma; I feel that they’re crossing a line at this very minute. If you look at the city of Kyoto, Kyoto has possibly even already crossed the line beyond which it is no longer a pleasant and enjoyable city. It’s no longer a city that young people are going to come to. In fact, they’re not. Young people have stopped coming to Kyoto. So, that’s a concern.

In the process of modernization, you assert that the old was tossed aside to accommodate the new; that to be modern for the older Japanese was to be Western. How in your opinion does Japan rate in its aim at Westernization and maybe more importantly, being a Westerner yourself, what do you think it means to be Westernized?

These are very complex issues. It’s true that the old was cast aside in order to be Westernized, but of course Japan is anything but Westernized. In fact, modernized is the word I would prefer to use. But I would say many Western values such as the legal system have not taken root to this day. There is essentially no functioning legal system even now. So, I’m not sure that Westernization is what has happened here at all except some outward forms – I mean, they wear jeans. But the clothes you wear is neither here nor there to my view.

The other thing is I’m not sure that the aim for the whole world is necessarily Westernization. Surely, the aim is some kind of humanization or some sort of values that are common to mankind; and this is where there are things to be taken from the West, but there are also things to be learned here in Japan or India or wherever. So, that would seem to be the aim, and I think it’s in that area that Japan is having trouble because one of the roots of the problem is that Japan has a tradition of closure. They were, in fact, closed to the world for almost 300 years during the Edo Period. They only opened up in l868 but it never really stayed open very long and then pretty soon you had the military period and then the war. Following World War II there’s been stringent control to keep Japan as closed as possible which still goes on. Very few foreigners are here and they’re not allowed to do very much.

So, what has happened is this: the bureaucracy, the all-powerful people who run this country only know Japan. If you go to Singapore which is also a bureaucracy, those people have studied at Oxford, they’ve traveled all over the world. They know how the world works, but Japan has its own ways and only those ways and that’s one of the reasons why I wouldn’t say they’ve become Western or Eastern, they’ve just become more Japanese. In the modern age when we’re all trying to transcend being just American, or just something or other, that’s a problem. Everybody else is somehow transcending, growing beyond what they used to be. Japan is still stuck in only what they used to be.

You speak of architect Sei Takayama’s observation that one reason for this state of affairs is the ability of the Japanese to narrow their focus. In Japan maintaining its own Japaneseness, in what ways has that been a detriment to the development of the country and in what ways has it been an asset?

Well, it depends on what you want to look at. Certainly in traditional culture, the ability to focus was everything: that’s why you have haiku – that’s what a haiku is. That famous haiku by Basho – an old pond, the frog leaps, the sound of water. It’s intense focus on one moment. The tea ceremony is intense focus on the tiniest details, the tiniest moment of picking up a tea bowl and everything involved in that. I’d say, that’s culturally very important and has been very valuable. That’s one of the Japanese contributions. If you look at economics, it was also a huge asset in industry. The reason Japan has such good quality control is because of the concentration on small details and the concern for them. Whereas the American approach is to just rush and ram things through and go on to the next. Which meant that while we were doing things roughly and rather hurriedly, the Japanese were refining. So, those are the advantages.

Of course, the disadvantage is that you don’t see the forest for the trees and that you tend to look at the small patch of rice paddy and say how nice and not look next to it and see there is a horrible factory and a giant flashing sign. Those things wouldn’t necessarily bother you. So, that’s part of what’s happened to the environment; rather than looking at the whole view, people are able to pick out that one little bit that they like.

You have also mentioned that the Japanese have a very keen sense of aesthetic beauty but no understanding of ugliness.

Yes, and actually I think that understanding of aesthetic beauty is still there. The tragedy is that the Japanese are not satisfied with Japan anymore. In their heart of hearts, deep down way inside in a place that most people never think of consciously, it’s a bore. That’s why they don’t travel in this country anymore. Domestic tourism is plummeting and foreign travel is skyrocketing and that’s because it’s no fun here.

You first came to Japan at the age of 12 back in 1964 and you left again in 1966 but went on to make the study of both Japanese and Chinese your life’s work. What fascinated you about the country then and what has held your interest for so many years?

Actually it started when I was nine in grade school. I went to a school where they taught us Chinese and I fell in love with the characters, writing characters. Then when I was twelve my family moved here and so what I felt about Chinese naturally flowed into Japanese. But I still have a China fascination. People ask me, “why Japan, why Japan?” And of course, it isn’t just Japan. It’s really East Asia that fascinates me. And I spent a lot of time traveling in China and in southeast Asia, so Japan is a part of that. As to why I stay here or have been here for so long…sometimes I think it was a kind of fate; I washed up on these shores and I had things to do. That’s a strange comment but that’s what I seem to feel about it.

The fascination of Japan? Well, I’m a romantic, an old-fashioned romantic and Japan was a very romantic country. It was a beautiful country; it had an incredibly elaborate, fascinating culture and the Japanese were romantics. They had created this romantic culture of geishas and moon on the bamboo and all of that stuff. And that, the shadows of it, the last bit of it that was there to be seen when I was child.

This is to me one of the real tragedies and partly what I was writing about in my book: I think every country needs to have some romance in order for people to live; to get through your life you’ve got to have a dream of some kind. Even super modern places like New York or Hong Kong are romantic cities. The way they’re constructed; the possibilities that people have. You can start out today as nobody and end up tomorrow in some incredible situation. Japan in its process of bureaucratizing and all the rest of it, has so thoroughly wiped out romance as to become by far the most prosaic country in the world. Everything goes according to system. There are no surprises. You lead your whole life, you go to high school, you take your exam, you go to college, then you go into a company, you’re there until you die. No one will suddenly get rich, no one will suddenly get poor. Everybody knows exactly where they stand. Every city looks exactly like every other city, every house looks like every other house – they’re all made out of the same plastic, they all have the same fluorescent lights. It’s prosaic beyond belief. I think romance is like bread or rice, people need a bit of it just to live and Japan is so short on that commodity that people are starving.

You write in your book that as living cities like Kyoto decay they will be replaced by copies, cities of illusion and historical theme parks. Japan is notorious in the world as the perfecters of the art of imitation. Do you think the time is coming that Japan will begin to recognize its own attributes and copy itself?

Oh, yes, it’s coming. One of the things that we’re now getting ready for is that there have been a lot of announcements made lately by the government about their concern over the decline of tourism and the way to revive it, they believe, is to build tourist sites all over the country. So, there’s going to be a massive amount of building new monuments of all types: recreated castles and recreated this, that and the other. There’s going to be a lot of that coming.

But are the good things coming back?

It would be nice if they were. It’s hard for me to imagine how some bureaucrats are going to design anything that satisfies the human heart. This is where we come to something a little more basic. The point is not to become more Japanese. For example, if they wiped out every wooden house in this area and replaced them with something super fantastically modern – suppose they replaced it with a Singapore-type look ( I’m not talking about Singapore’s government, I’m talking about the incredibly beautiful garden city that Singapore has created) that is brand-new and completely modern. I’m not sure that would be a completely fair trade but at least they would have gotten something out of what has been destroyed.

So, part of the question is what do you build that’s new and modern? In other words, beauty is not…I’m not saying that a person in kimono is beautiful and a person in Western clothes is not beautiful or a building built like an old castle is beautiful and a building that is not an old castle is not beautiful. That’s not the point. And just a mere reconstruction that has the form of a castle but without any heart of the castle is not going to please the heart. The heart is pleased by something else, I think. This is where elements of modern design must coincide with modern progress. I mean, I don’t see how merely building a big Disneyland that recreates the old satisfies anybody.

Many people around the world think of the Japanese as automatons; non-feeling human beings who just live by the system and have become so conformist-minded that there is very little sense of individuation. So one wonders, does Japan still have a heart?

If you look at the old kabuki play in which to protect the lord’s house, the retainer has to cut off his own son’s head and present it to the enemy as the head of the lord’s son, pretending that everything is all right …That was very moving and brought people to tears in old kabuki theaters. And that is because that’s what the Japanese do every day of their lives. Of course, they’re feeling people but the society forces them into strait jackets and forces them into situations where they have no say and where they’re essentially in small ways, all day long and all week long and all year long enduring that situation that I just described on the kabuki stage.

So, I certainly wouldn’t say that they’re automatons and not feeling. In fact, I believe that they’re suffering and that there is severe unhappiness in this country. I’m not sure I would have guessed it myself because it’s not so much on the surface. It’s when I wrote that book kind of by accident and suddenly got all this response that it began to hit me that the heart is still there.

You had taken a brief time away from this country to study Chinese and Japanese at Yale and then at Oxford. When you first discovered that your path was to absorb things Asian you were still a very young man. What are some of the richest experiences you’ve had along this path over these years?

Well, as I said earlier, I washed up on these shores. I’m a person who really drifted into certain situations rather than having planned and said, “I’m now going to do this and I’m now going to do that.” The first situation that I drifted into was a valley in the south in Japan, a hidden valley on the island of Shikoku called Iya which is sometimes called the “Tibet of Japan.” It was so remote that until the 20s it was almost an independent country. They have their own dialect. There was no road in there. The first settlers were actually refugees from a war in the 12th century and because it was so remote they fled in and then never left. I discovered this when I was in college and used to hike up there and found that it was littered with beautiful old thatch-roof houses, many of them abandoned because the villagers had left and had gone down to the cities. In those days I had the idea that I was going to be a hermit living up in the hills eating mist, I suppose. I found one of these houses and was able to buy it. It was practically given to me and I spent the next few years rethatching it, restoring it and through that process learning quite a bit about the old village life. That’s really my base. In the end I keep going back to that experience.

After all these years, why is it that you finally decided to write this book?

Well, there again, I’m not a person who decides to do things. I floated into that one, too. An opinion magazine, called Shincho 45 came and asked me to write one article about my experience in the village. I did and as I was writing that article, I also wrote about my concerns for what I saw happening to the mountains and the rivers. And to everyone’s surprise, including the magazine’s, we got a huge response. Suddenly letters were pouring in from Japanese who feel heartbroken about these subjects. So, they said to me, ‘will you write another article?’ I wrote another one and then I said, ‘well, that’s enough for Iya. Why don’t I do the next one on kabuki which was something else I was involved in.’ So, I did kabuki and then calligraphy and then kept going on. Eventually we had fifteen articles and they said, ‘let’s publish it as a book.’And it became a book. So, it wasn’t that I set out to make any great declarations. This again is something that happened. So, I am as taken unawares and surprised by my own book as anyone else.

Ultimately your book does not intend to be prescriptive but in merely describing the lost Japan, is that a sufficient means of addressing the dire problems that Japanese are facing here?

I’m not sure that it is, but I am a foreigner here. I’m not sure that it is appropriate for us foreigners to prescribe anything. Remember, we’ve been doing that for hundreds of years now as ‘white man’s burden’ and as colonialists; we’ve been preaching our heavy moralistic attitudes too the ‘primitive natives’ all over the world, trying to tell them what they should do. I am not sure that is appropriate for these times at all. I don’t want to tell the Japanese what they have to do. I think that they must work it out themselves.

Yes, but you had mentioned earlier that this is no longer a time of being just and American or just a Japanese; that this is a time of being a citizen of the world. I don’t see how we can live here and cut ourselves off from what is happening around us.

Of course that is true. That’s why I write. I can’t just sit back. I have to say something. I also feel though that one of the most important things is the diagnosis. The Japanese know something is wrong but they don’t quite know what it is. I hope my saying, “here’s what is wrong,” is a big step right there.

You’ve also studied calligraphy. Do you approach your calligraphic drawings from a western viewpoint or have you tried to adapt a traditional Japanese style?

Well, actually its more like neither of those. I’d say it’s Chinese style. Japanese calligraphy traditionally is very well-behaved. They had what they called ryugi, which are schools of calligraphy almost as strict as tea schools or Noh drama, with every tiny dot and slash determined down to the millimeter. Within that they had Zen calligraphy which was a little bit more avant-garde but even that was highly restricted. Whereas the Chinese had calligraphy as sheer play and that’s my calligraphy. So, I guess maybe that part is a return to something from childhood.

How is that recognized by the Japanese?

Calligraphy as an art form in general is almost dead in this country; so, the idea that you could enjoy calligraphy is an exotic one now. People come and see the things that I do which is pour a little wine, have some friends over, play music and maybe we’ll write some things together. So, I think probably the main attitude is surprise.

You were also involved with Oomoto-kyo for many, many years. How did that all begin?

Well, maybe I should say a few words on who they are. Oomoto is a Shinto sect which began in the 1890s with its own eclectic and ‘new age’ approach to Shintoism. They are what they call the ‘arts religion.’ The founder had said that “art is the mother of religion,” and so they have in their headquarters Noh stages and tea ceremony rooms, martial arts, pottery, weaving—all of these things are incorporated right into the religion. Twenty years ago they decided to start a seminar where they would teach these arts to foreigners in a one-month program, learning all the arts at the same time which is quite unique in this country. I was asked to come and help with that and then stayed on.

What do you feel have been your greatest contributions there?

I’m not sure that I’ve contributed anything but I would say that Oomoto has made great contributions; most notably to make these arts available to foreigners and even to some Japanese. The reason that is so important is that in modern Japan all of these arts have become highly rigid and codified: you sign on the dotted line if you do tea ceremony and you join a certain school or a certain sensei and you never go to another and that particular style is all that you even learn. Again, it’s the narrowing focus problem. You do calligraphy and that’s all you know. Whereas Oomoto teaches all the arts and is not particularly associated with any school or tea or Noh drama or anything else. So the student can see how all these things are related: how the movement of the feet in the Noh drama is related to the movement of Shinto priests which is related to the movement in the tea room; or you can see how in Noh lifting of the fan has a certain speed, a famous rhythm they call johakyu which is slow, faster, fastest, stop. It’s rhythm recognizable in kabuki dance or in the tea ceremony as you wipe the scoop or you fold the cloth. It’s all the same rhythm and only when you do these arts all at the same time do these realizations begin to happen. It’s a wonderful, eye-opening experience for the people who go through it.

Lastly, you conclude that at the very moment of its disappearance, Japanese traditional culture is having its greatest flowering. Can you explain this seeming paradox?

Well, I think that happens at the end of any age. I think it’s been true all through history; that at the moment of downfall … if you look at Athens under Pericles, Athens was about to lose its influence and became nothing ever after. And that was the moment when everything wonderful happened. So, I think this is a factor you’ll see everywhere. In particular, the interesting thing in Japan is you had a generation of people which include the designer Miyake Issei or the architect Ando Tadao or the kabuki actor Tomesaburo or the flower master Kawase Toshiro—these people who are in their forties or fifties grew up at a time when the Japan that I’ve been talking about was intact to some degree; they saw those mountains covered with virgin forests; they lived in those houses; they understood those rhythms that I was speaking about in the Noh drama or whatever.

At the same time, a generation earlier than that Japan was still too tight—too many rules and regulations, too tight a society, you had too much respect that you had to pay to your superiors and all of that stuff. So, the effect was that the older generation didn’t have the freedom to take that tradition and combine it with brand-new, modern things because they were bound-up tight in an old system. Whereas this group of people had a niche, they had a freedom to experiment and play with the new. So, among them we find people, I think, who are geniuses who’ll be recognized hundreds of years from now as among the greatest artists the world has known.

So, you look at the next generation, these are younger people who grew up in the plastic and neon and concrete cities who didn’t know the tradition and who have never seen the beautiful countryside and don’t know what it was about and only know a kind of cheap, instant foods sort of modern Westernization. They have little knowledge of the old and some of the worst of the new to draw on and so very little comes out of that generation. The flowering I am talking about is a niche of a certain age group mostly who have achieved wonders and are going on achieving wonders, so that it’s fascinating to watch what they’re doing.

And there is another interesting twist to this. Japan has the word, kata, which means a form, for example, in kabuki or Noh drama—a certain way of holding the fan or a certain way of speaking or turning the head. I think they have them in judo as well and other kinds of martial arts. I’d say once every four hundred years the chance comes to set the form, for what it’s going to be for the next four hundred. We had the last one right around the year 1600. The tea masters and the poets and the potters and the painters of that era se the forms which were followed right through to this day. The tea ceremony that we do today was established then. I think that’s going to be true in design and in kabuki and in flowers and in architecture. People are going to look hundreds of years from now at the forms being established by these people because of the fact that they lived in this critical niche and their experience can never be repeated. They were the people who knew the old and had the freedom to do the new and so they were able to do something which is going to impact Japanese civilization from here onwards. And in that sense, it’s a very exciting time to be here.

Kathy Arlyn Sokol and Alex Kerr have co-written a book called Another Kyoto.