[N]estled at the foot of the eastern hills, the small temple of Honen-in is a tranquil oasis of green. It stands on the spot where the great Kamakura reformer, Honen Shonin (1133-1212), used to pray six times a day before a statue of Amida. Few of the tourists who make their way along the nearby Philosopher’s Path bother to visit, yet it constitutes the essence of traditional Japan. So attractive was it to the writer Tanizaki that he asked to be buried here. ‘The moment you’re in the hush of the temple compound you naturally feel calm,’ says the protagonist of Diary of a Mad Old Man (1961).

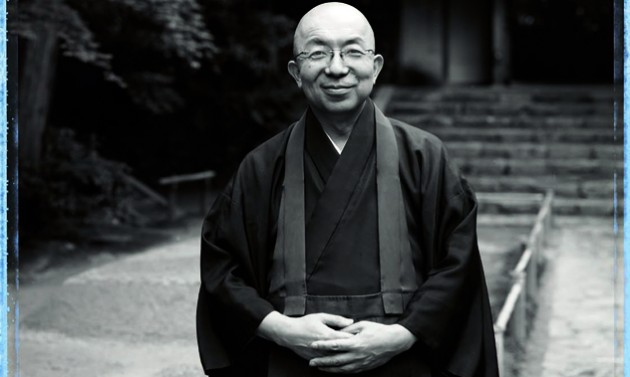

In recent years the temple has won attention not just for its atmosphere, but for its many events — some 50 art exhibitions and 60 concerts a year. There are also regular environmental meetings. It makes the temple more than just a spiritual centre, but something of a community space. The dynamism owes itself to the head monk, Kajita Shinsho, whom I am on my way to meet.

The approach to the temple leads through a mixed woodland, and in the balmy heat of late summer the filtered sunlight casts dappled patterns amidst the shade. Inside the entrance are two rectangular beds of raised sand, the raked patterns on which are like the changing ripples on a pool of water. It speaks of a setting where artistry meets spirituality.

I’m ushered into one of the reception rooms where I look through my notes. Born in 1956, the Rev. Kajita studied German at university before entering the priesthood. He became head at a young age and maintains a high profile in Kyoto’s cultural life: as well as founding a group that investigated the greenness of Kyoto supermarkets, he serves on one committee that gives planning advice and another that coordinates the city’s NPOs. He is also on the governing board of Kyoto’s Arts Center, and he gives advice on personal problems in a radio programme with the striking name of Bonze Cafe.

Temple Background For a man who wears so many caps, the shaven-headed priest exudes a genial calm. He talks openly and from the heart; here is none of the closed manner for which Kyoto is famous. Even the most probing of questions are greeted with a smile and measured reflection. He is the third generation of his family to head the temple, and when I question the hereditary principle, he tells me there are plus points as well as minus points to the tradition. In his own case he had always wanted to join the priesthood and has never regretted it. His devotion is clear. I get the feeling too that he enjoys the social aspect. There are some 600 paid-up households (danka) and maintaining good relations with them is vital to the running of the temple. Thanks to this, entrance to the grounds remains free.

The cultural events grew out of a chance meeting with an environmentalist studying the forest surrounds. This led to the setting up of a class devoted to the temple’s ecology, following which enquiries came from people interested in renting rooms. “Of course there’s a risk in opening the temple,” he says. “The noise, for example. And damage. But we have to accept that, we shouldn’t get angry. People are not perfect.”

Many of the events have a special quality. The best attended was an outdoor concert by the Native American flautist Carlos Nakai, when over five hundred people gathered to enjoy the haunting sounds as they melted into the dark recesses of the woods. But for Kajita the most memorable occasion was an exhibition by Kurita Koichi of coloured piles of soil taken from different parts of Kinki. The layout was in the form of a mandala, with 27 rows of 27 conical piles (the number has Buddhist significance). It provoked thoughts of man’s relationship to the earth and of the mystical notion of microcosm: “To see a world in a grain of sand,” as Blake put it.

There is no secret agenda to such events. “If people coming to the temple want to turn to Budhhism, it’s up to them,” says Kajita with a smile. He does, however, see a spiritual dimension for the surrounds offer a respite from the artificial nature of modern life. Here in the tranquility of the temple they can find peace of heart, and the bond with nature serves as a reminder that humans once lived in tune with the seasons.

Buddhist Perspective Every weekend the head monk gives sermons open to all, and for Kajita there are two basic ways of thinking: you either believe you can change yourself, which is the way of Zen, or you believe that human nature is a given, in which case you throw yourself on the mercy of Amida. That is the way advocated by Honen. If, as is often said, all spiritual paths lead to the same mountain top, then the important thing is not so much which path you choose but that you do indeed choose one. No commitment means no salvation.

As for the present state of Buddhism, Kajita sees a disconnect with the morality of the teaching. Three to four hundred years ago, he believes, there was a secularisation of the religion as a result of which it was debased into “funereal Buddhism” in which people are only concerned with dead relatives. The result is that those who think they are living good lives may in fact be bad from a Buddhist viewpoint. As an example, he cites wasteful consumption. Buddha’s teachings speak to a life of frugality; recycling is good, but refraining from use is even better.

Given all this, one wonders how the priest feels about the plight of modern Kyoto. Surprisingly, he is optimistic. The mediocrity of postwar development resulted from a misunderstanding of democracy, he argues: planners thought that it meant freedom for builders to do as they liked. But recent changes in the law to limit the height of buildings and restrict rooftop advertising show a more responsible approach. Yes, change is slow, but after thirty or forty years Kyoto will be a better place.

A Vision for Kyoto As for policy matters, he talks of the need to disperse tourists among the city’s lesser known venues rather than have them cluster round the same few famous sights. Another concern is the preservation of local character. Instead of a uniform approach, he wants to see diversity. Gion should be Gion-like, different from Nishijin for example. “It is the local communities to which Kyoto people have traditionally been attached, not to the city as a whole,” he says.

But it is when Kajita talks of consolidating Kyoto’s spiritual heritage that I sense the priest’s visionary nature. Above all, he wants a city that serves as a beacon of higher truths rather than one that is commercialised and profit-oriented. It’s a notion that reminds me of the role played by my home town of Oxford in the nineteenth century when it was championed as a stronghold of light and beauty amidst a rising tide of utilitarianism.

“Kyoto people should have more awareness of their heritage. They should remember the important things in life, not just profit. Religion is about our relationship to the world around us, caring for others and for the environment. After all, we don’t know how we will be reborn, so we need to think about that and cultivate a peaceful heart.”

With time running out, and others waiting to be seen, I take my leave and wander around the grounds. There is a moss garden of impossibly verdant hues and a carp pond whose gentle waterfall fills the stagnant air with the sound of constant change. Beautiful surrounds breed beautiful thoughts, it is said, and I wonder if the serenity of the setting has not rubbed off on those who live here. The aesthetic tradition is typified by the twenty-five flowers scattered daily on the floor before an ancient statue of Amida, symbolising the followers who accompany the deity’s descent to earth. It is just one of the temple’s many treasures. As I make my way back through the wooded approach, I can’t help feeling the head monk too should be numbered among them.

Photo by Matthias Ley