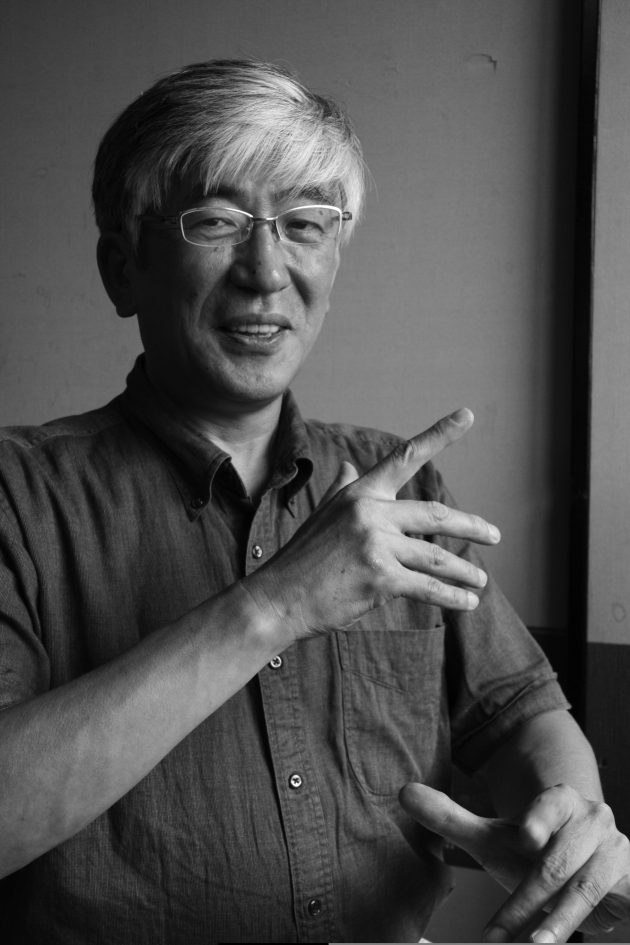

[B]orn in Kyoto four years after World War II, Kurahashi Yoshio started learning shakuhachi, the traditional Japanese end-blown flute, at age ten under his father’s guidance. Later studying under Matsumura Homei of Nara, in 1976 he performed his first solo concert, winning the Osaka Cultural Festival Award. Four years later he became director of the Mujuan shakuhachi school founded in Kyoto by his father, and shortly afterward began touring throughout Asia, Europe, Israel, and the U.S., playing and teaching shakuhachi. In 1999 Kurahashi released his first CD album, Kyoto Spirit, followed in 2001 by an album of traditional Chinese and Japanese music for shakuhachi. Since 1995, his annual intensive classes throughout the U.S. have become very popular. His sense of humor and generous attitude are well known to his students (who simply call him “sensei”), and to many others who enjoy traditional shakuhachi music. Today, because of his exceptional technique and a wide repertoire bridging traditions and cultures alike, Kurahashi Yoshio is sought by composers and musicians of many genres wishing to incorporate shakuhachi into their music.

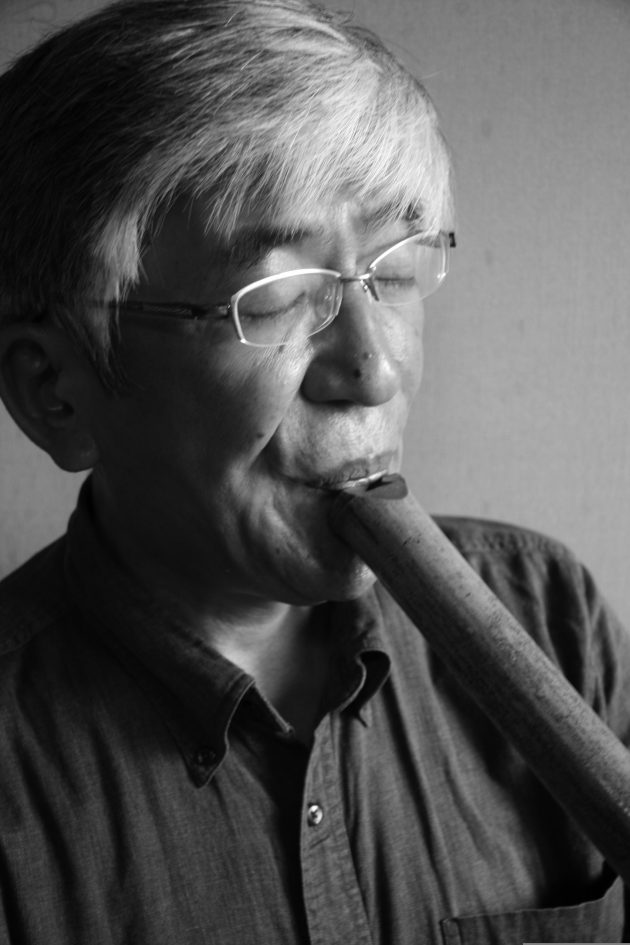

Sensei picks up an instrument, brings it to his lips, and softly blows. Notes flow fast, then slow. Fingers move like tiny birds, and a melody emerges. He’s clearly present, but also not.

On a warm July Tanabata morning, sunlight pouring lazily through the window, we settle onto zabutons in the upstairs music room at his home. Sensei recounts the early days, his views of where shakuhachi seems to be going, and his hopes for the future.

“In the ‘60s, when young, I thought shakuhachi was boring, old-fashioned,” he says. “I liked the Beatles and group sounds that were popular then.” His father, shakuhachi master Kurahashi Yodo, greatly influenced him too, though musically and politically they were very different. “My father forced me to practice…but I didn’t like it,” he recalls. Despite the harsh environment, Kurahashi also fondly remembers his father’s inspiration in developing his own style and musical direction.

Initially ambivalent about shakuhachi, at twenty his world changed. Practicing daily till exhaustion, “One day, through a crack in this world, I found a new world in the shakuhachi sound, a world my father didn’t know, that I didn’t know…an eternal world, where nothing changes. It was a very strange experience.” This resonates with how renowned scholar Kuki Shozo (1888-1941) has described the effects of Japanese and other music, like Debussy’s “La Mer” — freedom from time itself.

Struggling to progress technically and yet retain this freedom, Kurahashi recalls, “I gave up, and stopped practicing so hard.” Smiling, he adds, “Later, my friends said, ‘Recently, you became better.’” But he ruefully continues, “About this time, I also lost the ability to see [the other world].” Since then, Kurahashi’s remedy for regaining this vision is playing songs like “Jimbo Sanya,” “Tsuru no Sugomori [Nesting of the Cranes],” and “Mukaiji.” Probably his favorite, “Jimbo Sanya” is a wandering monk’s rendering from the 1870s of “Sanya,” an ancient meditative tune. “When I play these, I can forget notation, melody and rhythm,” he says, “and be like air…a long breath of music and sound.”

Still living in the family home near Kyoto’s ancient Toji Temple, where he was born and raised, Kurahashi relishes connecting with others worldwide through shakuhachi. Like monks of old, he shares his love of the bamboo flute through Mujuan (literally “abode of no place”), the school his father named after the composition “Muju Shin-Kyoku” (composed by the teacher and shakuhachi master Jin Nyodo, 1891-1966), its name taken from a verse in the Diamond Sutra.

“Traveling gives me opportunities to teach in many places in the world,” Kurahashi says. While most shakuhachi masters in Japan stay close to home, sensei’s style is as unique as each of the cities he visits, ensuring that the music remains vibrant and accessible.

On shakuhachi’s future, though, Kurashashi reflects, “Many students today aren’t serious. Basically, they don’t seem to respect Japanese traditions. They like shakuhachi sounds but not traditional music.” Though shakuhachi’s soulful sound is commonly the attractive force, Kurahashi stresses this alone is not enough: “Shakuhachi and traditional Japanese music differ from Western music. Shakuhachi pitch is different, the beat sometimes very free.” When young players immersed in computers and more rhythmically formal Western tunes encounter shakuhachi, many complain the pitch is “wrong,” or the beat is “off.” “Young shakuhachi players,” he says, “must change their concept about music… but many refuse.”

Kurahashi acknowledges computers’ benefits, but with a caveat. “Yes, they can play music… but the music isn’t correct, or flexible.” Though using computers with traditional pieces certainly creates some interesting tunes, such music “can become very boring, even dead. You can’t see another world.”

As with other arts, shakuhachi’s “traditional” characteristics are constantly evolving. Hesitating to call himself traditional, sensei’s eyes light up when discussing how the music is changing. The challenge [with any instrument], he feels, is for younger players immersed in newer music styles “to try playing traditional melodies. They should learn traditional pieces first, then try contemporary tunes.” The recent successes of Joshi Junigakubo (The Twelve Girls Band) from China and the shamisen-playing Yoshida Brothers in Japan show that traditional and modern elements can smoothly blend to create an attractive and vibrant sound. Creativity can be a force for change and for preservation.

Over the last 30 years, such creativity has helped spur dramatic improvement in players’ skills. For example, Kurahashi notes that a difficult daikan — a delicate, very high-pitched sound that decades ago only one percent of musicians could play — is today considered a sound for beginners. “I still can’t forget my father’s face after first hearing [technically adept shakuhachi master] Aoki Reibo [1935–],” he recalls. “My father was shocked. It was too good, beyond his imagination.

Technically, my father wasn’t so good, but he had something, something we had lost.” His father’s sound, he now realizes, was natural, like whispering wind and rolling waves: hard to imitate, even more challenging to play, yet perhaps more in tune with shakuhachi’s essence.

Whether for opportunity, fame, or that elusive natural sound, players and masters from all over Japan are now flocking to Tokyo, the modern capital. Long a rhythm beating in Kyoto, Japan’s cultural heart has shifted, sensei believes. Some feel this migration back to Tokyo is partly fueled by expanding egos. Sensei agrees:

“Discipline and competition are necessary for building players’ skills, but competition means always trying to play better than others. It’s strange. Shakuhachi music is called ‘meditation’ music; if playing fully you can lose your ego. But sometimes playing also makes the ego bigger, so many players think they’re unique or the best.” Kurahashi admits it’s a dilemma without an easy solution.

While enjoying the growing ease of living in Kyoto, Kurahashi also regrets its waning uniqueness. “Kyoto has become a city mainly for tourists,” he says. “Though seen as the center of Japan’s traditions, the city depends so much now on tourism.” Proud of his city’s long heritage, Kurahashi acknowledges that change is constant, yet muses on how Tokyo as cultural magnet and society’s changing priorities are affecting Kyoto, shakuhachi, and other cultural arts: “For example, many Kyoto government officials still see Kyoto as Japan’s cultural heart. But I think these beliefs are outdated. If Kyoto is to be the center of Japanese culture, the city’s culture awards must be open to anyone in Japan, not only people in Kyoto.” The old capital, he feels, can once again be a center for culture — traditional and modern alike — but only if it looks beyond itself.

As morning segues into afternoon, I ask about his Tanabata wishes. “Mainly,” he says, “I hope to continue playing relaxed and aware.” For Kyoto, he hopes for cultural rebirth, with more competitions and opportunities for all the arts. And for shakuhachi, that more people will listen to it and discover the beauty of its sound.

As a soothing melody fades, sensei slowly sets his shakuhachi down and rests. Eyes closed. Quietly, we savor echoes of whooshing wind and bamboo spirit — of tradition, set free.

Photographs by Stewart Wachs