It was actually as a geiko that I first went abroad.

William Gaetz, head of Columbia studios, came here from Hollywood in 1958 to get a close look at the geiko world for a movie he was making for Marlon Brando and Taka Miiko. He understood that the ‘sophisticated prostitute’ image was wrong, but he had to know more about what geiko do and are. Most of Sayonara was filmed on location, in certain Kyoto restaurants and at the Heian shrine, the Gosho and other locations. I was invited back to the American for the publicity tour. We performed dances, and tea ceremony and other entertainments at the Gaetz residence in Beverly Hills. We were very popular. I met Audrey Hepburn.

From there we went onto promote the movie in fourteen cities: Chicago, Dallas, San Antonio… For our Kyomai dances we had taped music, but the local voltage didn’t match our player. Incredibly, we found a professional in Little Tokyo, L.A., who could play not only shamisen but koto, too. Travel papers were issued by the U.S. Consulate in Kobe, but we still had to go to Tokyo for the actual visa. The rules were still strict in those days, and Japanese didn’t get to America easily.

At the U.S. consulate I had to promise I wouldn’t marry an American. So many women had, after the war, only to be thrown aside after the couples went to the States. It was a big headache for everyone, the girls, their families, and the Japanese consulates. With nothing to offer but their own bodies, the girls drifted into Oriental restaurants, bars and hotels. “War bridges” was the polite term, and they were responsible for a new image of Japanese womanhood. They couldn’t do anything, and they couldn’t get back to Japan. They were not in any sense the artists that women of the geiko world are supposed to be, just girls who sold themselves. It was embarrassing for someone from Gion-machi to deal with them, and of course we were taken to many such restaurants — Saito in New York; Nakanoya in Chicago — where all the waitresses were war bridges. It colored my experience in the U.S.

How did you come to be a geiko?

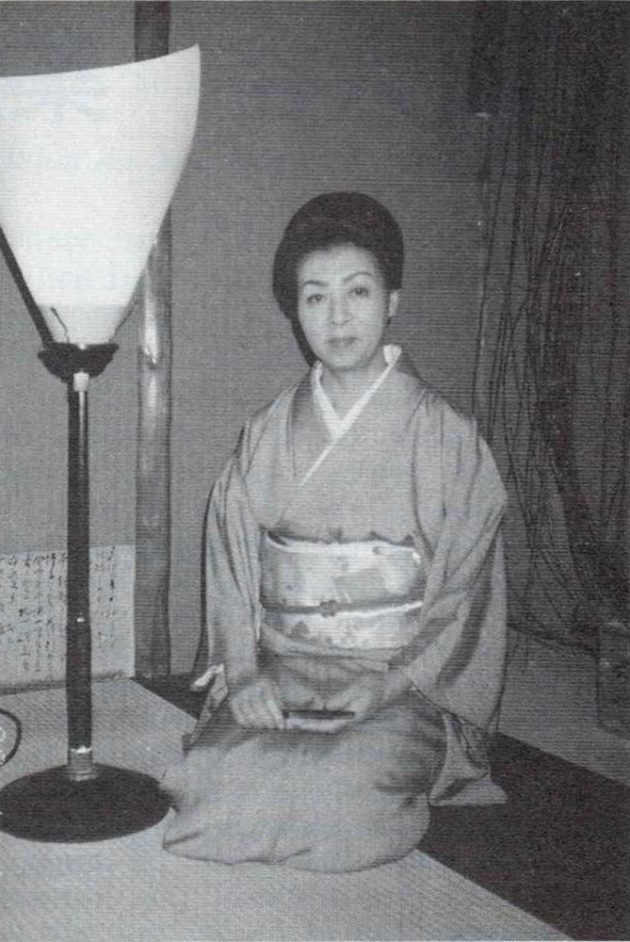

I am a third generation geiko in Gion-machi. My grandmother died when I was 7, but I have vivd memories of her in her finery, and of my mother, now 83 and still the kami [former geiko entrusted with the education of the neophytes] of an ocha-ya. It’s the end of the lineage; I have no children. I’ve retired from that world, so I don’t teach dance or other arts to the young maiko, as a kami might. However they do come to me to learn “the system” of Gion-machi: the ogyogi and tachifurumai [manners]. I show them how to speak, how not to be rough. These days many maiko are not Kyoto born; they’re from Hiroshima, Osaka, Akita, Shikoku, so they don’t know the Kyoto words. An excerbating factor, but not a problem. There is a certain system in Gion-machi — a system of rules and manners — and they don’t know how it works; that is a problem. These are not virtues picked up in a few hasty lessons, but learned with one’s whole body from a young age. The theatre arts, dance, flute, things like that — those one can learn with one’s eyes, if one has the talent, but the other aspects of our life, the humor, conversation, taste, even the way of pouring sake, these are things one grows up with, and many maiko of today haven’t had time to attain any depth.![]()

![]()

![]()

Is the makeup as complicated as it looks?

It’s theatre makeup, the same as kabuki with an oil underlay, hard oil, and then the foundation. There used to be lead in the skin ointments — which were once brown — and geiko died quite young. Geiko apply their own makeup, even the back of the neck, for which there are two styles. The regular bonsan style and the sanbon-ashi style for when wearing formal monstuki.

Do the shapes have meaning?

Of course. They take their cue from the neck itself. You see how the curve emphasizes the nape?

Are hands made up too?

They are whitened for stage performances, but not at other times.

And haguro? Tooth blackening is the strangest cosmetic I ever heard of.

You’re not likely to hear of it again. It was not always exclusively a geiko practice, though. For a period, brides’ teeth were blackened after the wedding. I can still dimly recall seeing geiko with blackened teeth. But that’s all in the past.

Are the geiko of Shimabara, in Western Kyoto, different from those in Gion?

Shimabara is gone. Only a few taiyu [singers] remain. There are five hanamachi [literally ‘flower towns’] left in Kyoto: Gion-machi, Ponto-cho, Miyagawa-cho, Kami Shichiken, and Higashi-shinchi. The dancers of each owe allegiance to different schools. Gion buyo, for example, is Inoue school, which as its roots in noh. In the other hanamachi you see Wakayanagi, Hanayagi, Bando, Nishikawa and Onoue schools. In Inoue-ryu jiuta songs are accompanied by a particular arrangement of shamisen, Kyoto and shakuhachi. Nagauta are sung to drums and flute. And we now sing both Kiyomoto and Katobushi joruri, like the others. The last real gidayu performer is here in Gion-machi. This may seem arcane to someone outside our world, but you can understand nothing about geiko without knowing at least that much.

Is there any importance placed on visits to the shrine dedicated to Benzaiten, the muse?

Certainly, although visiting some shrines, like Tenkawa in the mountains of Nara is complicated by the fact that women shouldn’t go into the mountains while menstruating. Some areas are entirely closed to women as you know. A maiko will visit Benten Shrine on Chikubu Island before a dance in which it is mentioned, for example. All Inoue-ryu dance teachers and geiko, from the iemoto down, visit Yasaka Shrine together in early August. It’s quite a spectacle.

But Shinto allegiances, like so much else, are diminished. There are no more keiko rehearsals, not like they once were. Even the Ponto-cho dances every spring and autumn — they dance to tape, you know. The Kamogawa Odori, too. Only the Gion Odori is still danced to musicians. But the shamisen players are disappearing, and geiko too. In my day there were 600 of us, and we had to dance at every sixth show. But with all of our other duties there were no more than four days off each month. We worked for twenty-five, but at least one of our free days was taken up with tea ceremony. With fewer girls (there are now about 70) each dancer is needed for every performance, and of course the service of a maiko now costs much more.

It’s all become so expensive, even the kimono. The guests are necessarily wealthy, but they are also younger, uninformed, not the kind of man who can discuss the all-important world of theatre. Naturally, their aspirations reach no higher than simply craving the company of a made-up girl; they want a mistress. With older guests it was all from the heart. A man’s attitude to his geiko was really quite “My Fair Lady.” A man was a true patron; he would take a young girl under his wing and polish her like a jewel, actually bring out all that was good in her. The young men know nothing about theatre. They can only show their ardour by buying expensive kimono, or giving their girl an apartment.

Patrons have changed because all of Japan has changed. The splendor of Gion, or Ponto-cho, which were once islands in a sea of grey, has been duplicated in Tokyo and elsewhere. The daily life of an urban Japanese simply has more art and plentitude in it than a generation ago.

I’m from the last generation of true maiko who were born in Gion, and it will never be the same. A maiko doing tea is now no different than any ojosan [young lady of breeding], because ojosans have caught up, in the matter of image and appearance. In my youth I was a tomboy, but I was tamed. There is no one to tame them now. Maiko can go to a café or cinema unchaperoned, even alone. That is how they learn the ways of the world; their conversations are from the movies! There are girls who go shopping in Hong Kong on the long weekends. We couldn’t, but who’s to tell them not to?

As a maiko did you choose your own kimono?

Of course not. We wouldn’t have had the good taste. But once dressed we wore them as if they grew from our bodies. Now the girls wear Western clothes in their free time. You wouldn’t know them to be maiko.

You once told me something to the effect that young women no longer know how to speak to men

A conversation between friends is not satisfactory because it leaves no traces. Certainly girls might still master the artifice of service, of arranging flowers or whatever ; but when they don’t understand something you can see it on their faces. The face blanks — we call it a shiran kao. Look, at age sixteen maiko are still half children, their heads jammed with information from television. I’m not so old myself — 53, neither a youth nor decrepit with age. I ‘bloomed’ later than girls do now, not long before the current generation, so I do understand them, which only means I am stuck between generations. These girls are too young to handle what they know, and the kami are too old to understand them. We have what you might call instant maiko. Instead of training from the age of six, they do a one year course at eighteen. A maiko should be this: an artist who deals with one person at a time. That’s the root of it. One learns everything as if it is for the benefit of a single individual. Modern maiko go to college with all the other kids. It is meaningless as education, and worse, it undermines their training because at college you don’t study for the sake of another person, do you? That’s a few years spent doing something completely useless. Bad enough for the youth generally, death for an entertainer. And it’s men who lose from it.

If that’s part of the wave of post-war culture, surely it will end, like all waves.

But not before all the sempai have died out, and the spirit has dissipated. I walk through Gion in the afternoon when they are supposed to be practicing with musicians, and all I hear are tapes. When I was a child the musician came to my house, and my movement and my sense of ma came from the resonance of the shamisen strings themselves. A geisha is a professional. ‘Gei’ means art, but we now have artless artists. There should be a new word.

There was once a lot more support and respect from popular culture. Did that instill pride?

Kogure Michiyo, Wakao Ayako, in “Gion Bayashi” was it? Directed by Yoshimura Kozaburo. I couldn’t say they were our models — probably the reverse — but they were equal to their roles. It’s true, the movies look elsewhere for stories, and traditional woman-types on television are rather standard. It’s funny — when that film came out everyone in Gion-machi felt a little… uncomfortable. That level of entertainment is missed now.

When a certain popular singer was revealed to have a lover in Gion while unofficially ‘engaged’ to someone else, how was the scandal received in Gion?

It was just bad. Do you remember the Keeler girl in England? I’m sorry, that kind of thing is just not Gion. The Uno scandal was even worse, because the woman was absolutely not of the karyukai [“flower and willow world,” the traditional pleasure quarters]. The karyukai has its good deeds and bad deeds like any other milieu, but it does not offer its scandals to the world. K-san is of course still around, but there was a feeling of extreme distaste at what happened, especially in the sense that the story was largely fabricated, out of the simple fact that, quite legitimately, she had accompanied him to a concert or two. There was nothing more to their relationship than that until someone decided the attention would suit them. The media are brutal, I would even say violent, after what I’ve seen.

In a way, the ‘news’ itself was proof of the lie, because if there was really a relationship I can assure you would never hear about it. I only wish K-san had put as much finesse into her dancing as she showed in riding out that episode.