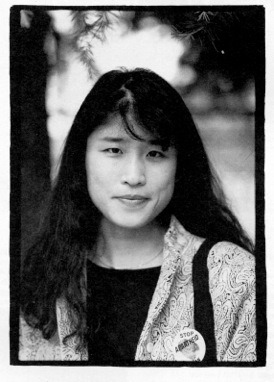

Yumi Lee is a third-generation Korean Japanese. She works actively to improve the lives of Koreans in Japan and to raise the awareness of their situation, especially among the Japanese.

I grew up in Miyazu [in Kyoto Prefecture, on the Japan Sea] — a kind of small-town paradise for a child. People know each other so there was no need to talk about your background. Then we moved to Kyoto, and in junior high school my friends began to use “Chosen” [Korea] to mean something disgusting. They had no idea what they were doing. The word Chosen has, in fact, a very lovely meaning: cho is “morning” and sen is “fresh,” but the original meaning has changed here. It’s so sad.

I went to Korea during the summer when I was in junior college. I saw that Korean people were lively and very emotional, energetic and spiritual, so different, and so free. I felt so free. I realized, it’s so stupid to be discriminated against! I don’t have anything to be ashamed of.

When I came back I gathered my courage and began to use my real name, Lee, in Japan! I started to study about myself, about Korean people, about Japanese society. And I resolved that I wasn’t going to be ashamed of being a Korean any more. After my announcement of my real name, I think, my fight started.

I had wanted to be a physical education teacher, but Koreans are not allowed to teach in the public schools. Japanese corporations, including JAL and Japan Travel Bureau, don’t hire Koreans. They have all sorts of excuses. So I worked part time, but it was depression time for me. Finally, I became a stewardess for Korean Air. I was very lucky

I started training in Seoul, and everything was so happy. I was studying Korean very hard, but my Korean was like pidgin Korean, and Korean people said “why can’t you speak Korean?” and I lost my confidence. Who Am I? I wasn’t Korean because I didn’t speak Korean and Korean people in Korea didn’t accept me. And oh, I love Korean people, but, they don’t understand our situation in Japan.

I was not angry with them, because until the end of the war Japan exploited Korea, just incredibly. It was beyond description. They lost their language, their culture, their names. After the war they felt liberated and started to develop pride in Korean culture and language. But Korean people here in Japan are not liberated yet. For example, we still don’t use Korean names. By law we can use them, but socially we can’t.

I had such mixed feelings about everything. There was something inside me telling me that this is not right. I knew that there must be something I could do, so I started by writing to newspapers about Korean issues; I started to tell people. At work my back hurt so much that I had to quit Korean Airlines. So now I work as an English teacher, and I entered Friends World College last September.

My approach to this Korean-Japanese issue has been to find out my roots, find out about Korea and its beautiful deep history and heritage, its language and culture. And also to look at what I can do in Japan to get rid of discrimination and prejudice.

Last year I had a chance to teach kids in a grade school in Kyoto from September to March. The teacher is my volleyball club mate. I drew attention from newspapers because it was such a revolutionary thing for a Korean person to do in a Japanese school; Korean issues are so much hidden in society, swept under the carpet. I taught them positively about Korean language and Korean culture. It was so good. I got so many cards and letters from the kids: “I was so interested about Korea.” “I didn’t know Korea was so near.” “I like Lee Sensei.”

My other approach is to help Korean young people in Japan. They are in a desperate situation. In some areas, like Minami-ku [southern Kyoto], there are quite a few Korean students, but there is no guidance for teachers on how they can encourage them. The worst case is kids with second-generation parents who ask teachers not to tell their kids that they’re Korean. It’s incredible. Just imagine what kind of situation these kids will have. They will find out because when they become 16 years old they have to be fingerprinted. It’s so scary. It’s really a terrible shock.

Through my study of this Korean-Japanese issue I have realized that four major factors prevent solutions: the first is Japanese education. In schools we are not taught about Korea. The Japanese schools are hiding so much about their past. Also, Japanese education teaches a sense of values in which people are not supposed to ask or think, and it’s a one¬-way method, from teachers to students, not back to the teachers. That doesn’t give students a chance to create their own ideas and opinions about issues. These young people are not informed, and if you are ignorant it’s so easy to reinforce discrimination and prejudice. I remember once the teacher gave us flyers about Burakumin and Korean people. Satistics. How many Burakumin, how many Koreans in Japan; they are discriminated against, and let’s not do it. That’s it. Nothing about why the Korean people are here, or what we can do. They teach who not to discriminate against, but don’t give enough concrete sense of those people as real to engender any sympathy with them.

The second is that Japanese society is a vertical, hierarchical society. Always somebody has to be up and somebody down. There is so much pressure that needs an outlet that Korean people are often used as scapegoats. Last year, a politician announced that some North Korean organization was dangerous. The next day, Korean students were attacked in Kyoto; their Korean chogori dresses were cut and they were kicked and insulted on the street. There were ten incidents a day, all over Japan. A grade school student was interviewed and said “An old Japanese woman asked me why I am here.” This tiny Korean girl!

The third is geographical: Japan is isolated. So they feel, many of these Japanese, we are pure. They don’t want to be mixed, even though history now shows clearly that Koreans have come and assimilated before.

The fourth is apathy, caused by hard work and study. They don’t have time to think about anybody else. These four, insufficient education, hierarchy, isolation, and apathy maintain the Japanese Korean problem.

I want to give Korean people strength. For example, now I welcome interviews and any kind of attention from the media, and I get so many letters and response calls from Japanese and Korean people who have been in the same boat. like “I’ve been feeling this but nobody spoke out and I felt so small, but I felt so good when I read your article.” That’s my concern because Korean people go through self-hatred and loss of identity. They just hide their identity and it’s sad. It’s painful. Mentally it’s such a big burden. And now I feel so free.

I used to think that I was doing this only for the sake of Korean people, but now I think it is also for Japanese people. They can’t have this obstacle any more if they want to be an international country. Next year I’m going to go on a tour in the states, so American people can get to know something about Japanese social problems, and hopefully Japan will realize that they have to change too.

So I’m not taking any political approach. My concern is to make people aware. This is my first priority. If I appeal to the human heart, that’s what will change things.