[I]magine Kyoto in the year 1868. The shogun had resigned, signalling the start of wholesale change, and it seemed everything was up for grabs. To symbolise the new dawn it had been decided the emperor should move his capital to Tokyo. When the day of his departure came, thousands of citizens lined the streets, many distraught and in tears.

The relocation ripped the heart out of Kyoto. With the emperor went the great aristocratic families together with a small army of retainers and craftsmen. A city that had been founded as an imperial seat had lost its raison d’etre .

To fill the vacuum the city sought to reinvent itself, and the post-Restoration period was one of remarkable vigour. Part of the efforts focused on 1894, the 110th anniversary of Kyoto’s foundation, and the inauguration of a grand parade named Jidai Matsuri (Festival of Ages).

No expense was spared, for this was to be a grand advertisement for the city, the likes of which upstarts like Tokyo were incapable of matching. Costumes were made in traditional manner, using the weaving and dyeing skills of Nishijin. Take the silk kimono of Murasaki Shikibu, for instance, which has cloud patterns woven into a russet fabric said to be worth $8000. Yet it is only partly visible, for it is worn beneath a court robe that is itself an exquisite item.

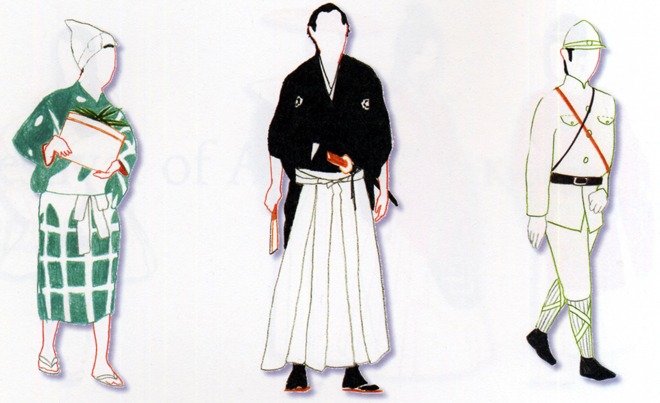

The parade takes place on October 22 each year, the date of the city’s foundation. The original 500 participants have swelled in number to some 3000, and with their colourful outfits and decorated horses they gather in the Former Imperial Palace to fill the empty space with pageantry. As the procession leaves the southern exit, it is as if the stream of Japanese history is flowing out of the imperial well-spring. The symbolism is intended, for the festival is unashamedly pro-emperor Though it begins with the fighting in pre-Meiji days, there’s no place for the famed shogunate hit squad, the Shinsengumi. Instead it leads off with volunteers in the Imperial Army and samurai intellectuals honoured as ‘Patriots of the Restoration’.

From these heady times, the parade works backwards through the ages like the unfurling of an illustrated scroll. From each period selected tableaux come to life. The Edo Period (1603-1867) is represented by a deputation to the emperor, together with notable court ladies. The period of unification, the Azuchi-Momoyama Period (1573-1603) features that great benefactor of Kyoto, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, followed by the entry into a strife-torn Kyoto by the unifying warlord, Oda Nobunaga in 1570.

The military attire of Muromachi samurai (1333-1573) is offset by the women of Ohara with bundles of firewood on their heads to sell. There’s pointedly no place here for the usurping Ashikaga Takauji, who initiated the Southern Court period when for fifty years Japan had two rival emperors. The Kamakura Period (1186-1333), which saw power move away from Kyoto in the form of the first military government, is represented by archers who attempted to restore imperial sovereignty.

This leads into the Heian Period (794-1185), Kyoto’s golden dawn, with the dominant Fujiwara family followed by the great women writers of the age, including the poet-beauty Ono no Komachi, the witty Sei Shonagon, and the incomparable Murasaki Shikibu (whose Tale of Genji celebrated its millennium in 2008).

The end of the procession – and its religious dimension – is a sacred palanquin bearing the spirits of the first and last emperors to reside in Kyoto, Kammu and Komei. The two men guard the city now as tutelary deities. It is as if they maintain the imperial presence even though the actual emperor is elsewhere.

As a city Kyoto acts as a spatial counterpart to the parade, for the architecture speaks to the ages no less than the colourful costumes. Memories are set in wood and stone at every corner, and the physical structure is imbued with mythic status through its historical connections. ‘No city or landscape is truly rich unless it has been given the quality of myth by writer, painter or by association with great events,’ wrote V.S. Naipaul. One stands for instance in the small garden of Shinsen-en, sole relic from the original city, and marvels that the legendary priest Kukai once performed a rain-making ceremony here. Dragons were thought to move in the depths of the pond, and emperors composed poems in the grounds (far larger then). Physically the garden is unimpressive; imaginatively it has a transcending presence.

This city of the mind hovers in a parallel dimension to the physical city. I’m aware of it every day of my life, from the moment I draw my curtains and gaze out on Shimogamo Shrine whose surrounds date back to an age before Kyoto was even conceived. My way to work takes me along the Kamogawa, much praised by poets, and past the Edo-era study of the historian Sai Ranyo, who coined Kyoto’s epithet, ‘City of Purple Hills and Crystal Streams’. From there it is a matter of minutes to Sanjo Bridge, which marks the end of the former Tokaido path from Edo. One can’t help thinking here of Hiroshige’s 53 way-stations and the twelve days it took the hardy folk of those days to walk it all.

It was on the river bed by Sanjo that public executions were carried out, and it must be the thought of their angry spirits that makes this the only bridge on the river not to house the homeless. There’s another execution site further south, where in 1619 fifty-two Christians were burnt to death as part of the clampdown against foreign influences that culminated in the age of isolation. More happily at Shijo one passes a statue of Izumi no Okuni, whose performances on the dry river bed sparked interest in a new form of entertainment dubbed kabuki (crazy).

At the next bridge, Gojo, is a monument celebrating the famous David-and-Goliath sword fight between the dainty Yoshitsune and the giant Benkei at the end of the Heian period. It is here that I part ways with the herons wading in the River Kamo for a more turbulent stream – that of the traffic heading westwards. My destination is a campus adjacent to the Nishi Honganji, the great True Pure Land temple that was built in early Edo times. Its main hall is dedicated to the religious reformer of Kamakura times, Shinran, and with the many treasures inherited from Hideyoshi’s one-time palace the temple speaks too to the grandiose tastes of the Momoyama period.

Any trip through Kyoto transports one similarly in time, for beneath the veneer of modernity the past is ever present. Even the most prosaic of physical appearances is transformed by an awareness of history. True enough, the Golden Temple is enhanced by Mishima’s dazzling prism, but the humdrum building on the site of a pre-Restoration sword fight is also lent lustre by its associative resonance.

It is this wealth of history that makes Kyoto one of the world’s foremost cities. The tourist office lists 17 World Heritage sites, 90 outstanding gardens, 177 festivals and 471 notable temples and shrines – not forgetting the 82 special trees and rolling schedule of seasonal flora, for nature-viewing is part of Kyoto’s rich heritage too. No wonder that by some estimates this is the second most visited city on earth after Mecca!

In Kyoto’s Festival of Ages, one period is conspicuous by its absence: the present. It’s as if time had stopped in 1868 with the Meiji Restoration. In literary terms too the city is defined as ‘the former capital’, or Koto as Kawabata titled his elegiac novel. The valedictory tone of the writing is typical of a tendency to write off the modern city. In Lost Japan Alex Kerr claims postwar development has killed the city’s appeal, with the 1964 building of the Kyoto Tower a symbolic stake through the heart. ‘The Americans spared Kyoto in the war, but the Japanese destroyed it afterwards,’ runs a well-known quip.

Yet this is at best only a partial truth. The traditional city may be in retreat, but change is inherent in the Japanese way of seeing the world, and to expect Kyoto to remain as it once was would be at odds with the Buddhist-derived philosophy of mujokan : nothing is permanent, all things will pass, life is constant flux. ‘The relationship between tradition and change in Japan has always been complicated by the fact that change is in itself a tradition,’ notes Edward Seidensticker.

Viewed in this light, post-Meiji Kyoto constitutes an age no less worth celebrating than any other. It began with rapid modernisation in the years following the emperor’s relocation when, improbably, a citadel of tradition was transformed into an eager innovator. A string of firsts poured out of the city: the first state schools, the first water-power station, the first large-scale works, the first trams, the first film projection, the first public library, and the first symphony orchestra.

The legacy of this exciting time has enriched the city in many ways. Waters from the Biwako Canal (built 1885-90) not only feed industry but the creations of master gardener Ogawa Jihei as well as cherry-lined canals like the much-loved Philosopher’s Walk. The film industry set around Uzumasa turned Kyoto into ‘Japan’s Hollywood’ and gave the world classics like Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950). And the educational innovations helped make the city a centre of learning with the highest number of tertiary-level students outside Tokyo.

Architecturally, some of the country’s first Western-style buildings appeared in Kyoto, and these stand today as attractive monuments to the country’s early days of Westernisation. Examples abound: city centre banks, the villas of rich industrialists, the National Museum, and the buildings around Doshisha University which was founded by one of the first men to be educated abroad.

It is since the 1950s, however, that the greatest changes to Kyoto’s cityscape have taken place. Watch Mizoguchi’s Gion Bayashi (1953), and you see the camera pan over the tiled rooftops disrupted only by the occasional pagoda. Since then the city centre has been transformed into a teeming mass of concrete high rises. It makes for a dynamic mix as modern apartment blocks tower over wooden houses and neon signs cluster round stores of Edo-era crafts. It has led too to increased diversity. This is a city of high tech industry as well as tourism, of Kyocera and Nintendo as well as Kiyomizu and Nanzenji. While most tourists flock to the temples, others head for the newly-opened International Manga Museum. And while some go geisha watching, others come for the science conferences for Kyoto is a convention city too.

Yet those of us who love Kyoto could wish to see greater sensitivity in terms of city planning. The modern high rises are of a depressing mediocrity, and when one compares them with the creative flair of a city like Shanghai one can only bemoan the shocking waste of opportunity. For every attractive building like Kyoto Concert Hall, there are countless examples of the nondescript. Do the exteriors of Kyoto Station and Kyoto Hotel add to a city once renowned for its aesthetics? Where are the preservation policies that protect European cities? Where are the pedestrian precincts and car-free city centre? Where, for heaven’s sake, are the pro-cycling and other environmental measures one might think would characterise a city that lent its name to the Kyoto Protocol?

For all that recent years have seen hopeful signs of a change for the better. The machiya boom is a case in point. These wooden merchant houses, unique to Kansai, reflect the lifestyle of Edo-era merchants. Restricted by law to two storeys, the houses have a narrow frontage but extend long and deep, with small gardens in the middle and at the back. In the 1970s and 1980s, they were disappearing at a rapid rate. Now they are prized by young Japanese and many have been converted into trendy restaurants, adding to Kyoto’s deserved renown as a gourmet’s delight.

Other positive indications include a greater concern by city hall with design. The Kamo riverside has been converted into a pleasant park with space for pastimes of all kinds from barbeques to gateball and concerts. Junctions in the city have been rounded to allow space for trees and greater space for pedestrians. There is a more vibrant feel to the downtown area with open-air cafes and craft shops run by young people. And recent regulations have come into force restricting building height, mandating greenery on high-rise roofs, and limiting the use of advertising boards.

As a citizen one would like such reforms to be more timely and thorough-going. Japan is a deeply conservative society imbued with Confucian ethics, and those of us working here are all too aware of the resistance to change. This is after all the only democracy to have had a virtual one-party government for more than fifty years. On the other hand, once the consensus reaches a tipping point, things can change with great effectiveness as all pull together in the new direction. With a new generation succeeding the baby boomers at city hall, one senses the tipping point may be close at hand. To paraphrase an old saying, the death of Kyoto has been much exaggerated. Rather than killed off, one could say it has been given a make-over. As a result the city has vitality as well as history; innovation as well as tradition; diversity as well as harmony. In Kyoto’s Festival of Ages, the present too is an age worth celebrating.

JOHN DOUGILL is the author of Kyoto: A Cultural History (Signal/ OUP), and is a professor at Ryukoku University in Kyoto. In 2006, in quest of Shinto’s shamanistic roots, he travelled overland from Lake Baikal to Busan, then followed Jimmu’s legendary journey from Kyushu across the Inland Sea to Yamato.

Illustration by DANNY