[W]aiting in the snow at the Ryoan-ji bus stop on a Kyoto winter morning in 1964, without an overcoat or money to buy one, my anxious reverie about the day ahead and language classes in Osaka was interrupted by a woman who came out of a nearby house and, seeing me standing there, went back inside and returned with an overcoat which she helped me into. It was a three-quarter-length brown coat, and warm. That evening, on my return, I found the house and the owner, who invited me in. And when I got up to go, leaving the coat, he said, “Keep it. I’ve got another.” That was my introduction to Kyoto and I knew that I had brought my wife, Barbara, and our children to the right city. It had been a huge gamble with so little money, choosing to go to Japan, Australia’s former enemy, but we’d made it!

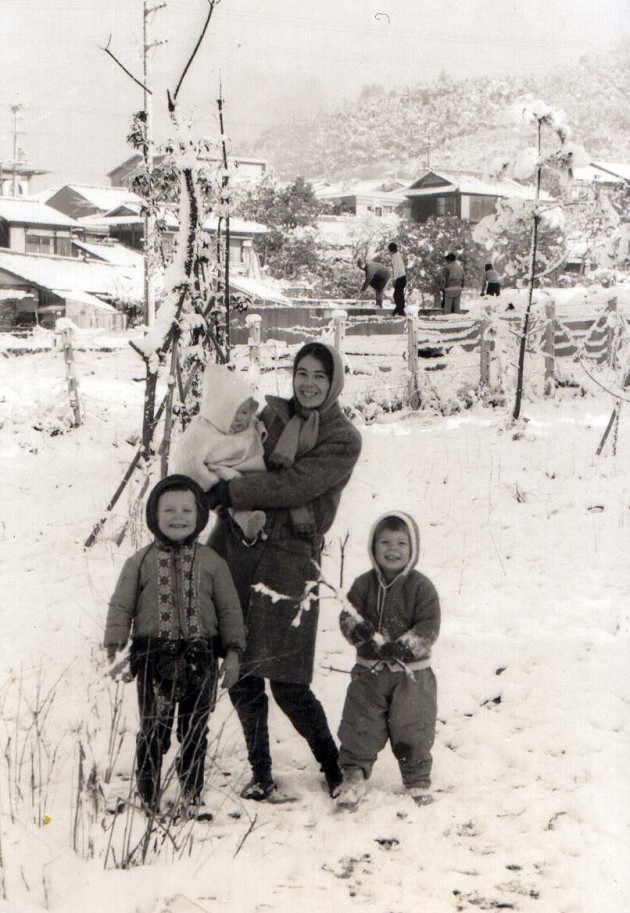

We were living at Kinugasa-shita-machi in a small ‘hanare’ (a couple of rooms, small kitchen, bathroom, verandah and garden,) found with the help of another exceptionally generous person, Kimura Mikio. By the time I’d bought futons, heaters, kitchen utensils and winter clothing for the children, there hadn’t been anything left over from my Mombusho scholarship. I wore the coat through three winters and I never forgot that unknown woman and her husband. We were living in a traditional house with ‘tatami,’ ‘shoji’ and ‘fusuma,’ hot in summer and very cold in winter, and which Barbara described in a letter home, referring to its geometry, as like living inside a Mondrian painting. The famous zen garden of Ryoan-ji, with its raked white gravel and fifteen stones, was around the corner. It sat in the mind, and later, when I was trying to describe our country to fellow post-graduates at Kyoto Fine Arts University, I depicted Australia as a huge zen garden ‘karasansui,’ floating in the South Pacific, a bit ragged around the edges where most of us like to live, a good view being had from space. When the first ever exhibition of Australian art in Japan, Young Australian Painters, was held in 1965, a map of the country was on the catalogue cover.

Japan was not high on the travel itinerary for Australians of my generation due to the war and the bitterness it left and also due to the colonial legacy of the British Empire to which Australia had belonged. England was ‘home,’ next door, so to speak, and artists and writers headed for London; a few went to Europe and the U.S. My experience was, despite the war and family involvement, different and I knew Australia, not England, was my home. Japanese studies were not yet in place in Australian universities, despite the fact that the first scientific research institute in Sydney, the Kanematsu Memorial Institute, had been founded in 1933 at Sydney Hospital. In our years in Kyoto it was possible to count Australians on one hand. And so it turned out that I was the first Australian sculptor and printmaker to do post graduate study in Japan without first going to England or Europe.

My background could have been summarized thus: the stories of Urashima Taro, Yoshi San and O Kiku and The Burning of the Rice Field, found in Victorian primary school readers, always reprinted during the war years; the Australian War Memorial publications, Khaki and Green and Jungle Warfare, with their stories and illustrations; the media of the day including comics; service on the cruiser HMAS Australia which bore a bronze plaque commemorating the captain and crew who had died as a result of a kamikaze attack; an awareness of the influence of Japanese art on modernism; the post-war relationships with Sydney potters; and that wonderful movie, Rashomon. That was it!

The year of our arrival, 1964, was a big year. It saw the first Olympic Games in Asia — in Tokyo; the first Nobel Prize in Science/Physics awarded to a Japanese scientist, Yukawa Hideki; the first high-speed trains between Tokyo and Kyoto. In those years, Kyoto was the destination for many people and, before the term ‘multi-culturalism’ had any currency, we found ourselves living a multi-cultural life with people from all over the world, very different from life in a diplomatic or business enclave. All sorts of intellectual and professional threads were being found and re-found in the woof and warp of a new time frame, one which saw people on the road, seeking enlightenment/satori in Zen sect temples, renewing friendships with artists of the Mingei movement.

There were architects from Brazil, economists from the US (one, Hector Bolitho, from Australia) and scientists and scholars from Europe. Students came from Ethiopia, Iran, Lebanon, Spain and Switzerland, countries that had not been at war with Japan, as well as undergraduates from all over Asia as part of war reparations. There was a steady stream of people from the Americas and Europe. We were living and studying with the first Japanese generation since Akira Kurosawa’s to be free from the ideology of fascism and life under a military dictatorship, young men and women who had grown up in the world of the black market, malnutrition and hard times after the war. It was no accident that the best music could be heard everywhere in city cafes. All in all, it was a great time to be in Kyoto.

When I applied for admission to the sculpture department, the then-head of school, Tsuji Shindo, wasn’t too sure if this foreigner would fit in. There are profound differences when it comes to attitudes towards authority in Western culture. In its Australian variant, authority is historically connected to stress regimes, our convict/jailer founders and ancestors, colonial authority, and the experience of war. Respect has to be earned; seniority is no guarantee. I remember a Japanese sculptor who had the audacity to have an exhibition downtown before he had completed his studies. He was kicked out! That couldn’t happen in our art schools.

Besides, coming from a world of this or that thinking and one of geological stability to one that rocks all the time, we’d also come from one rich in space per person. Some time after I began work in very cramped workshop space with seven other Japanese sculptors, transporting work with them for firing to the ‘noborigama’ where one bought space on the basis of that taken by a standing person. Tsuji-sensei invited me up to his studio and offered me a slug of mountain hooch. I had been accepted.

We had also been accepted in our new neighbourhood in Higashiyama just up from Sanjusangen-do. We had moved to a bigger, still traditional, apartment with a ‘tokonoma,’ one where ‘mukade’ (centipedes) could drop out of the ceiling onto futons on summer nights. There were lots of conversations out in the street about what we fed our kids, the oldest of whom had now started kindergarten.

Our children opened doors, made us approachable. At a strawberry gathering event at the local kindergarten, a Japanese woman married to a stateless European, someone who had lost his papers in the bombing of Kobe, came up to Barbara offering friendship. In time, she would ask about the possibility of migration to Australia for her family, despite the fact that, at that time, Australia was still a closed country due to the White Australia Policy (1901–1972.) They did migrate and their children are now professionals in their respective fields with families of their own.

In the mid-sixties, Kyoto was a city in transition. The Tower had gone up as had a new railway station, the second in its history, which would, in its turn, give way to a third, a huge secular temple, and provide a new focus for development. A new conference hall went up. The old timber and tile, low-profile city, saved from atomic bomb destruction by Roosevelt’s Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, was, like sandstone Sydney, having to adapt to new technologies of glass and concrete. First to go in both cities were trams.

Australia had been the last inhabitable continent to build and know the city. In 1964, Sydney, its oldest city (then only 176 years old) saw, as a result of Jørn Utzon’s Opera House, the centre of town shift to the harbour overlooking the famous building, and anyone and anything in the way evicted or knocked down. In Sydney, contemporary and public sculpture was thin on the ground, still is, can’t compete with Sydney surf. So to arrive in Japan and see Rodin’s Burghers of Calais in Le Corbusier’s museum in Tokyo and in Kyoto The Thinker ‘thinking’ outside the National Museum, and other work around the city, that was a revelation. Suddenly sculpture was everywhere — in temples and out in the streets with their roadside shrines. And shortly after our arrival a Miro exhibition opened.

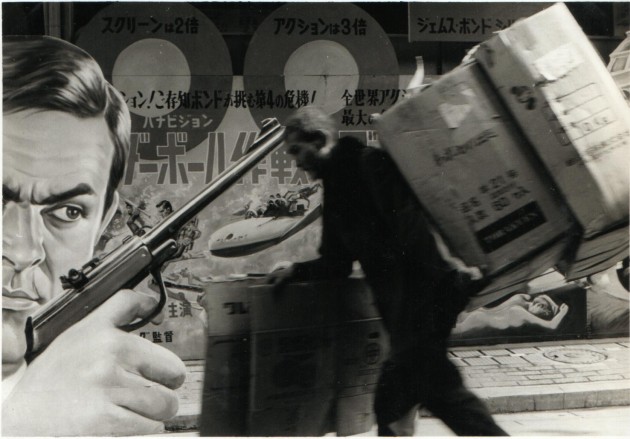

Downtown, the Festival of the Ages took place each year. Popeye angled for non-existent fish over the heads of passers-by and, at street level, giant cutouts of James Bond pointed his gun at them. The participants in many demonstrations (motivated by sixties civil rights and the war in Vietnam) would take to the streets. We couldn’t join them because of our student status. In Australia anyone, regardless of status, can join a protest.

Thanks to Mr and Mrs Stimson and their visit to Kyoto in 1926, a great tradition in the art of sculpture, evolving over the centuries, had survived in Kyoto and Nara, a tradition that in its first seven centuries resonated with the medieval sculpture of Christian Europe. In 1963, Sept Siècles de Sculpture Japonaise (Seven Centuries of Japanese Sculpture) by Geneviève Daridan was published, a comparative study destined to influence Endo Shusaku’s novel of 1965, Foreign Studies. I was beginning my studies in the long journey of Buddhism across Asia from India at end point, Japan.

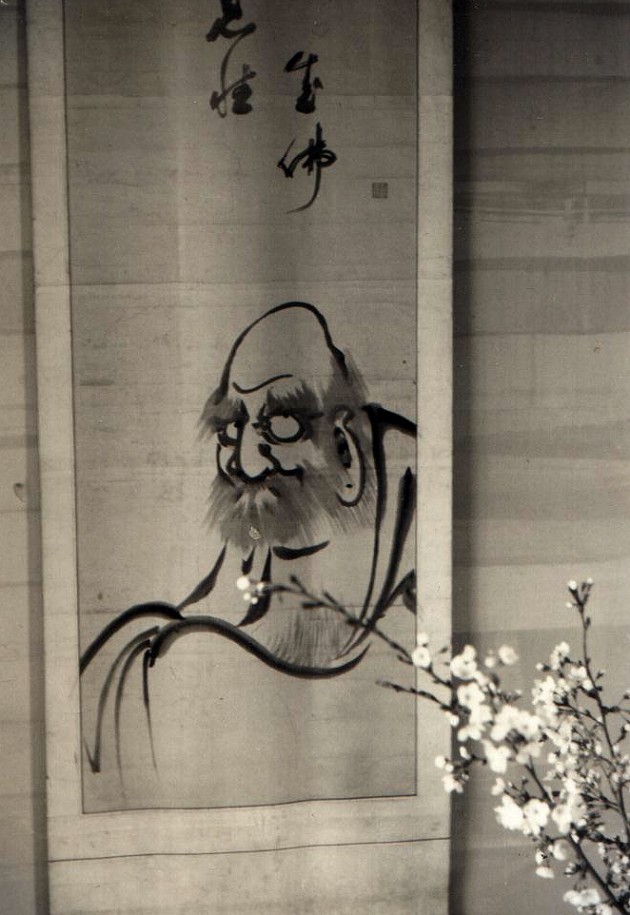

Down the bottom of our street, Minami Hiyoshi-cho, inside Rokuharamitsuji, the image of the blind monk, St. Kuya, ‘walked’ through the centuries with the prayer, “Namu Amida Butsu,” issuing from his mouth in the form of tiny images of the Buddha. And that is an image which the medieval Christian, Guido, the Carthusian, would have understood. He wrote, “All creatures are like syllables in a psalm that God is singing…”

In the mid-sixties the radical work of Enku and Mokujiki Shonin was still being discovered in out-of-the-way rural villages. These pilgrim monks, who worked in the 17th century, had left their Buddhist monasteries which had become, across the country, the thought police of their time after the proscription of Christianity, and hit the road, making, in the case of Enku, thousands of wooden images for poor villagers, using a small hatchet. These images have vitality, marry form and content, and stand in marked contrast to the otherwise effete sculpture of that time. My history professor, Mori Toru, of Ritsumeikan University, would invite me to accompany him to a distant village when a discovery was made. He opened many doors which would have otherwise stayed closed.

And though it hadn’t been on my horizon, for the first time I became aware of images in bronze, wood and lacquer of the contemplative life, the meditating figure which in Buddhism is nearly always male — unlike in western culture where it is usually female. Every now and then, it was important to go on a pilgrimage to see an image on show for just one day in the year, Ganjin’s, for example. Miss it, come back next year. To the discovery of Buddhist imagery was added that of Shinto which the American scholar, Langdon Warner, described as ‘the nurse of the arts’ in Japan.

We never did get to the great shrine of Ise, Shinto’s most sacred site. Nevertheless, the animism of Shinto imaginatively connected to place helped me to understand the ancient indigenous Aboriginal cultures in Australia and their need to have their sacred sites, although unmarked by sculpture or architecture, protected.

Between us, Barbara and I, aided by a an exchange rate of 360 yen to the dollar, haunted secondhand bookstores in Kyoto and in Tokyo and put together a library of images across all periods and places and an amazing collection of books, covering everything from farm houses to Noh. While we were in Japan, there were many exhibitions by artists and craftsmen and women who had survived the war. The printmaker, Munakata Shiko, although nearly blind, exhibited regularly. His pre-war Disciples of the Buddha, huge woodblocks, had lined his air raid shelter and survived for new editions.

Kuroda Tatsuaki, in Kyoto, was making beautiful geometries in lacquer and every Friday night he and his wife welcomed the local sculptors and craftsmen into their home. At the time of our departure from the city, one night Barbara, too, was invited to join us, so breaking the all-male tradition.

Looking back, I can’t remember any public image honouring a woman in Kyoto; maybe there is one now. Perhaps that was because the feminine was subsumed in Buddhist imagery. Odd now that I think about the women: Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shonagon who wrote the first novels The Tale of Genji and The Pillow Book.

However there is a powerful image in Hiroshima, a woman with her children, fleeing the city, as we found out in the summer of 1966 when we went to stay in a company house at Utsukushishima for a week.

We were cared for by two women, one of whom we never saw as she bore keloid scars on her face and was too ashamed to meet us. So we came to learn about the ‘hibakusha,’ the technology that created new groups of marginalized human beings and the problem of imaging when it comes to the genetic damage caused by radiation.

Images and imaging define us as a species. In 1966, the Chinese Cultural Revolution broke out and an Australian friend wrote from Shanghai that she had just seen a truckload of Buddhas go by her window on the way to the dump, escorted by Red Guards. Decades later Al Qaida destroyed the remains of the giant Buddhist images at Bamiyan, the crossroads of the pilgrim routes for Buddhism in the ancient world, iconoclasm was back, this time with the suicide bomber targeting the innocent.

Kyoto and its thousands of temples and shrines were spared the firestorms and urban holocaust of the twentieth century; thanks to Stimson who crossed Kyoto off the list of cities preserved for a nuclear attack (after the collapse of Germany for which the bombs were originally intended) and to General Groves who stopped Curtis Le May from napalming the city. “The [‘Target committee’] wanted Kyoto because its people were, ‘more highly intelligent and better able to appreciate the significance of the weapon…’ [This was] a leap into nuclear absurdity…for it was not clear how ‘highly intelligent’ people could appreciate if they were dead nor what difference it would make if they could.” (The Rise of American Air Power, Michael Sherry, Yale University.)

In our time in Japan, there were over two hundred and seventy nuclear tests across the planet, and, ever since the war in Korea, there had been threats to use nuclear weapons. China tested its first weapons and our neighbours advised us to take an umbrella to guard against fallout when we went out.

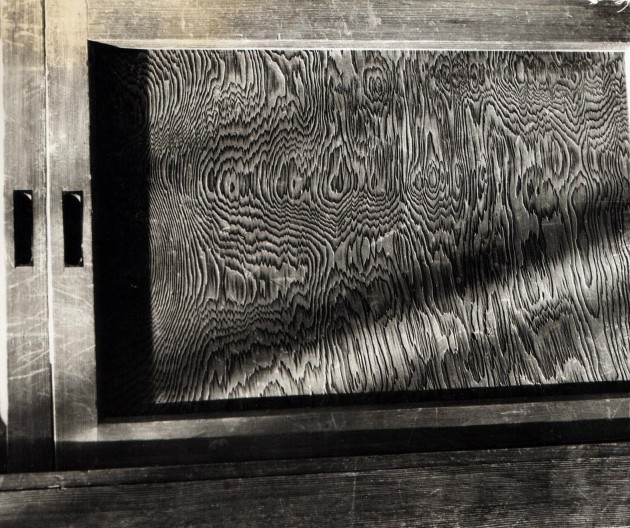

We had begun to record the ordinary around us, from the time we arrived. Our houses and the manner and materials of their construction taught us a lot, and right outside our first place at Ryoan-ji we watched and documented a house being built with traditional materials.

But, as a consequence of our visit to Hiroshima, we decided to take an even closer look at our neighbourhood, the vulnerable realities of life, the shops and the people who get up early and keep a city working. Graham Greene wrote that, “a city consists for each man of no more than a few streets, a few houses, a few people.”

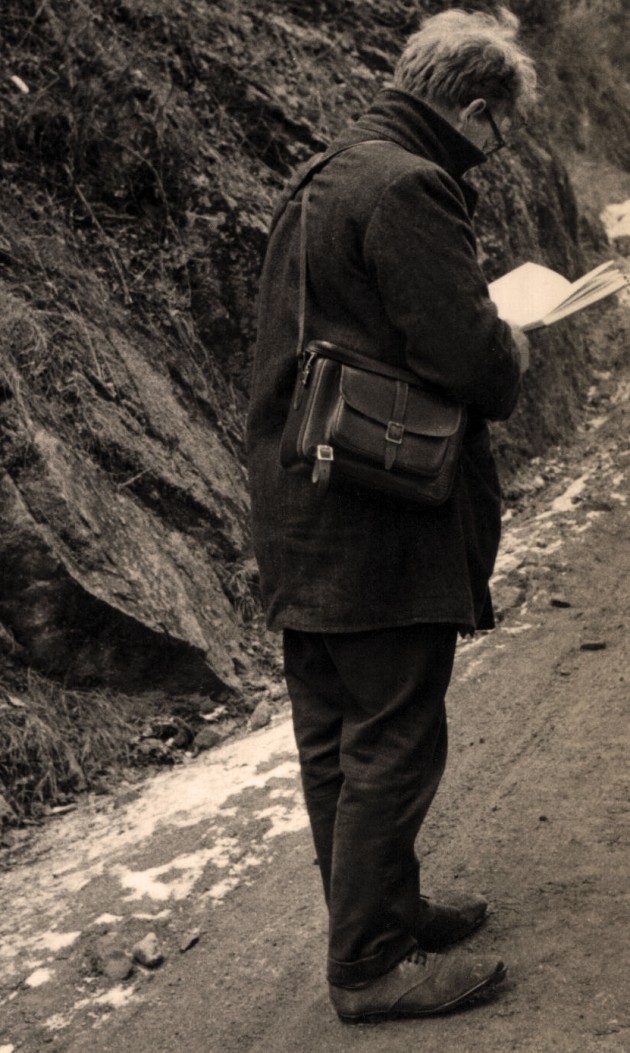

Through a summer, I walked the town, taking note of the expression that marks a street, a particular house, a love hotel, a pawn-shop, a pachinko parlour, a stretch of the river, nothing big deal, nothing that would make the pages of the National Geographic. Barbara saw things that I didn’t see; she did the shopping, observed habits and noted customs, patterns — and she used the old Minolta SR7 with perception. There were no supermarkets, no 100-yen stores and nearly all goods were locally made.

We took hundreds of photos and thought that, one day, we might get around to publishing a book, one that might help open eyes, shape reconciliation. Sad to say, we never did. Other travels in the world, making sculpture, going broke from time to time — life and our six brave kids who always came with us put an end to that idea. (Our third child was born in Kyoto and received a wonderful doll from my professor, additional to an old stone Jizo Sama he and his wife had given to Barbara before the birth)

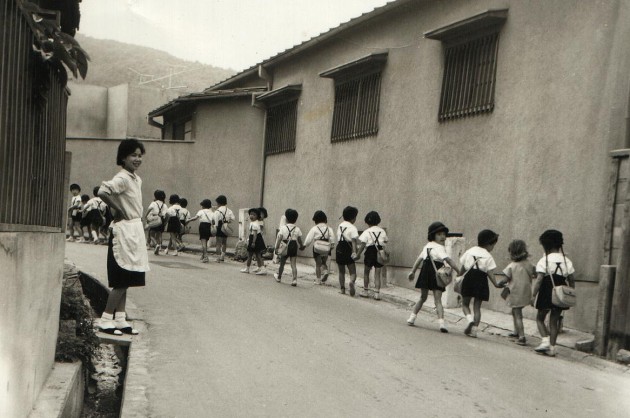

The thing about the ordinary is the way it can be transfigured in a moment; as with a human face, so with a city. Like any other city, Kyoto revealed itself in the moments when we were least prepared. It happened on my way home from my studio in Gojozaka when snow flurries danced and caught the light at night. It was the huge, seemingly stationary ball of the sun floating in mist on short winter days — look away momentarily and it was gone. It was the last colour of a few persimmons hanging high, out of reach, outside a window in late autumn; Arashiyama in spring; a summer night in Higashiyama and fire on the mountains (during Obon) and the annual syntax of festivals. It was the voices of children who called out for one another as a crocodile line of kids wound its way from house to house on their way to kindergarten and the understanding that school playgrounds sound the same everywhere on this planet.

One day, I hope there will be an image in bronze of an elderly American standing outside Kyoto Station welcoming visitors to the city he saved back in 1945. It’s not every day that someone saves a city and that is (just in case we’ve forgotten) part of the story behind the Burghers of Calais.

Bill Clements, born 1933 in Melbourne, Australia, is a practicing and exhibiting sculptor and printmaker.

All photos by Bill Clements