KJ’s Ananya Mayukha interviews Julie Gramlich, a Masters student at Kyoto University, researching female entrepreneurship. Originally from San Francisco with cultural roots in Japan, Julie worked for a female founder in the Silicon Valley before receiving the Japanese Education Ministry’s MEXT scholarship to study the entrepreneurial environment for women in Japan. As part of this research, Julie has interviewed over 20 Japanese women in a range of fields: those who’ve started medical programs, bakeries, and networking platforms, among other businesses. You can read more about Julie’s work on her website, www.juliegramlich.org

Julie: What would you like to get out of this interview?

Ananya: That’s a good question. It’s really open-ended, and I’m just curious to see where it goes.

Julie: Okay. That’s how I am too.

But I think what I’m most curious about is why you’re doing what you’re doing.

That’s a good idea. I can get to that.

My parents aren’t entrepreneurs. They’re far from it. My dad was a government worker—he gave food stamps to homeless people in San Francisco for 33 years—and my mother was a housewife.

I think part of what led me down this path is that I’ve been working for a long time, and I’ve always really enjoyed working. At the age of 14, I started working for a local District Supervisor at the San Francisco City Hall. That was about the earliest that you could start working legally in San Francisco, and then I continued to work as much as possible to earn pocket money, and to help pay for my college fees. I was able to self-finance 85% of my college tuition through working, scholarships, and subsidized loans.

After college, I worked at Google for a few years, before jumping ship to join a small startup with a female founder. That was a really good idea, because the company was so small that I got to try everything: sales, research, user testing, design prototyping, educational videos, and so much more. One time, my boss couldn’t make it to some event for female founders, so she sent a few of us instead to act on her behalf. We showed up and said: “hey, we’re not female founders, but we’d love to meet you!”

There, I became really good friends with a woman who was mixed-race like me and a female founder herself—Tracy Lawrence of Chewse. We were exactly the same age, yet she had started a company while she was in college. She’d already had to employ people, fire people, work through hurdles with her cofounder, and live on a couch for a while. But she was so level-headed and compassionate through it all. In fact, she even taught me how to surf one time—she’s just a very cool, well-rounded, exceptional young woman. So those women were very impactful for me.

Then when I heard about the Japanese Education Ministry’s MEXT scholarship, I decided to apply to research women’s entrepreneurship and empowerment. At the time, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was working extremely hard to empower women. So I thought, “I am heavily invested in women entrepreneur events in San Francisco, I know a lot of women founders, and I’ve worked for one. Why don’t I meld these things together?” Japan was already working on public policy initiatives to empower women, so it was perfect timing. But it was also something I was inherently passionate about.

When you say inherent passion, what do you mean?

That’s a good question.

It couldn’t be something like, “I want to research running methods.” I used to be very passionate about running, but that was more of a phase—a flippant passion. Women entrepreneurship is something I am more fundamentally interested in—something I deeply care about. I am fascinated by the experience of women starting businesses in a very male-dominated society. And not only that. Japan is also a very homogeneous culture, where everyone is encouraged to act in unison with the group and to maintain harmony in society. Under such circumstances, these women entrepreneurs dared to be different, dared to stick out, and dared to be something other than a housewife!

That said, I’ve never honestly thought of myself as a feminist. Other people have put that label on me, but I am fundamentally a humanist! I do believe there should be complete gender equality, but also just human equality. It could be gender, race, age, disability, or so many other things. But Japan is not necessarily there yet. They’re still working on women’s empowerment, so the MEXT scholarship was a really good opportunity to focus on that.

How did you find women to interview?

When I first came to Japan, I didn’t know anybody. So I just had to start telling my professors, classmates, and every person I met, pretty much, “I am researching women entrepreneurs in Japan. Do you happen to know any female founders that I could interview?” That also led to some self-selection, because in the beginning, I couldn’t speak Japanese very well, so I ended up interviewing more women who spoke English fluently. But as I became more confident in my Japanese, I was able to interview more people who couldn’t speak English. Slowly but surely, I gained connections to many amazing women in Japan.

What has inspired you about the women you’ve encountered?

If you look at the OECD gender equality statistics of 143 developed countries around the world, Japan is consistently among the worst. Based on my personal experiences with Japanese people that I know, the vast majority of women work at part-time jobs with no benefits, while also taking care of the household and children. Historically, taking care of all domestic activities has been the number one priority for Japanese women.

For example, in my mother’s generation, almost all women are housewives. So in this context, when I meet women who have actually started a business, I am always in awe and have deep respect for them. They’re taking an enormous risk and working against society’s expectations. And I suspect that’s also a reason why many Japanese women entrepreneurs are unmarried or divorced.

In fact, I interviewed a woman—Yoko Yamada—who divorced her husband and then started a business because she needed to earn money for the first time in her life to support her son. She decided to launch a consulting business, training new company recruits about the meticulous Japanese manners system based on the hierarchy and seniority of employees. Despite having to take care of her son all by herself, she spent countless hours at night reading, writing, and researching everything she could about this area.

Yoko shared how right before her first consulting job, she couldn’t sleep at all the night before because she was so nervous—after all, she was previously a housewife, with virtually no work experience. And yet, Yoko persevered against the odds, and worked very hard to accomplish her dream of becoming financially independent, with a successful business in an area that she was passionate about. As a result of her hard work, Yoko began receiving more job opportunities, and now travels all over Japan to teach business manners to new employees who work in large Japanese companies.

Another woman I interviewed—Miki Yamamoto—started her own bakery. Unlike her peers, she’s still successfully married. Since her husband works full-time at a traditional Japanese company, meaning that he works very long hours, Miki takes care of their children in addition to her bakery business, as she has a bit more flexibility. Although this means she effectively works two jobs, Miki truly loves what she is doing, and is very passionate about making her business successful, while also doing the double duty of taking care of the kids.

A third woman I interviewed—Kanoko Oishi—established a patient-centered medical clinic and rehabilitation center in Tokyo with over 120 employees and renowned doctors. After working at McKinsey for 12 years before becoming the 2nd female partner in Japan, Kanoko decided to leverage her business strategy skills to launch a business with two male doctors.

Even with the backing of two male doctors who acted as her cofounders, Kanoko still faced countless hurdles as a female CEO in Japan. Many people had trouble respecting or even acknowledging the fact that she was the CEO, often speaking directly to her cofounders instead. Furthermore, even though she is not married, she still wears a wedding ring to avoid potentially awkward and unnecessary situations with male counterparts. Even with all of these obstacles, Kanoko always focused on the positive, thinking: “Because of these challenges, I have had to work so much harder to earn people’s respect, and that’s why I’m so successful.”

After each and every interview with a Japanese women entrepreneur, I felt so encouraged to work harder toward my own personal dreams. Their spirit of breaking through the bamboo and glass ceilings is truly awe-inspiring.

-630x945.jpg)

What you said about being a ‘humanist’ really resonated with me. And that made me wonder: have you interviewed any non-females who are doing interesting entrepreneurial work?

Yes. Many people that I talk to have expanded my focus by asking questions like, “What about interviewing the woman’s husband (if she has one)? What about her kids, or the people around her, or women who are just working at regular Japanese companies? What about interviewing men?”

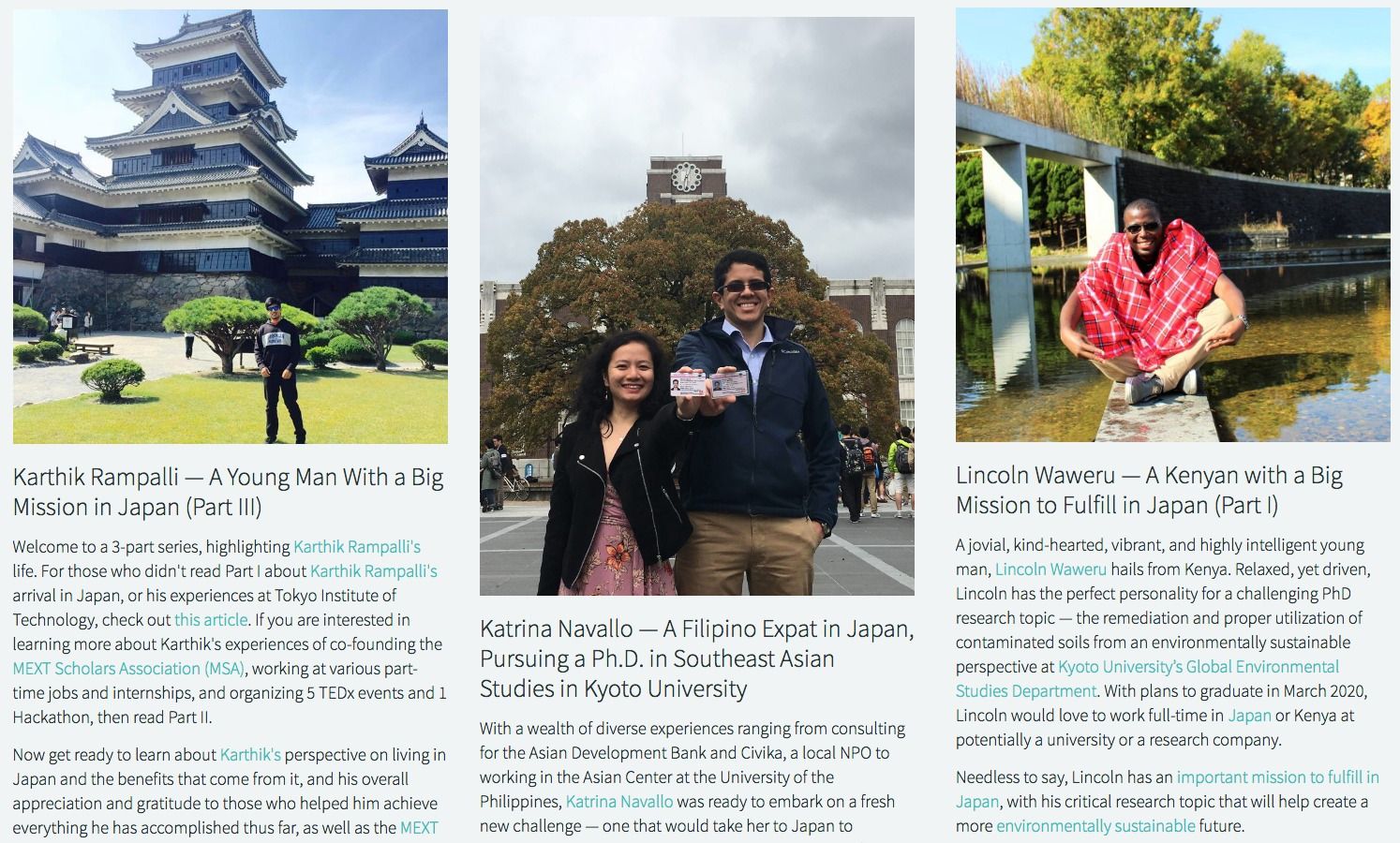

In addition to my research, I started to support a startup in Japan that is trying to create a hub for foreigners who are adjusting to life in Japan. For this company, I’ve interviewed a few MEXT scholars who are studying in Japan, including Karthik Rampalli from India, Katrina Navallo from the Philippines, and Lincoln Waweru from Kenya.

The best thing about the MEXT scholarship is that I’m in classes with people from all over the world. In America, I didn’t know as many international students, but in Japan, my friends are from very different backgrounds. I know so many exceptional people with really interesting stories, and I enjoy writing about them, because they’re my friends. Well, I’m not just trying to promote friends, but I’m promoting people who should be promoted.

Yeah. This reminds me of something you wrote on your website: that you like when people ask about your ethnicity. Why is that?

I used to like it, because I felt that people were inherently curious and genuinely interested in learning more about me. In fact, I even interviewed and wrote short stories about mixed-race people living in the United States, which may have been a precursor to me interviewing Japanese women entrepreneurs.

But when I moved to Japan in April 2016, I started feeling very self-conscious, because people would stare at me all the time. They may have been trying to figure out whether I was Japanese or not, or they may have been staring, because I wore sunglasses, bright clothing, and sleeveless shirts.

In Japan, I realized that people cover up everything with sun-proof black clothing when they go running, for example. They also cover their faces with black visors to protect themselves from the sun, when biking or running. Plus, everyone wants to be the same, and no one wants to stick out.

But in San Francisco, where I was born and raised, being unique, independent, and different is celebrated. So when I went back home after 6 months of living in Japan, I felt a huge sense of relief. People there wear whatever they want, or even occasionally, wear nothing. And reconnecting with that kind of freedom was so important for me. I realized the value of truly being myself and feeling comfortable in my own skin, no matter what I look like or how I dress.

That really changed my perspective, and I came back to Japan with the attitude that as long as I was respecting others, I wouldn’t care so much about how others thought of me. And people still stare, but I don’t care.

I just love hearing all this.

Really? Thank you so much. Can you tell me more about your story then, too? What are you passionate about?

Well, my research background is in end-of-life care, and I spent my past few summers talking to patients in hospitals. I’m not sure exactly what drew me to that, but I’ve always enjoyed talking to people about why they are here, and what they think their lives are supposed to be. Though I met someone earlier in my travels who really pressed me on the question, “why are you so interested in other people?” It never felt like something I had to explain, and it’s still not something I can fully explain, but a lot of it comes down to wanting to finding my own reason for being alive.

That’s a really big question you’re trying to answer. It would be interesting to figure that out for yourself.

I have waves of thinking “it’s really important to interview people and gather perspectives,” but then I go into dips of, “why am I doing this?”

That makes sense, because it’s all about motivation, and every day is different. But I think what drives me is the long-term perspective of wanting to contribute and wanting to do as much as I can while I’m here. I don’t want to waste my time. And I really like having something that drives me—something that gets me out of bed and gives me a reason for living.

This might be a strange question, but if you were going to die tomorrow, would you feel like you’ve done your work here, or do you feel like you’re working on something you need to continue?

That’s a really interesting question. I mean, there’s the short-term reality check that in a year and a half, my scholarship ends, and I’m going to have to figure out a role. But recently, I’ve asked myself, “why am I not starting my own business?” I’ve thought about it in the back of my head but I’ve never had the courage or confidence, and I still am not fully there.

So in that sense, if I died tomorrow, no, I would not have finished everything that I want to achieve in life. And by everything, I mean that besides finishing my research, I definitely want to start a company. Ideally, a social enterprise, where giving back to society is the number one goal.

Do you see yourself as an entrepreneur?

No, actually. But I guess, yes, if you expand the definition of “entrepreneur.” I once attended a really good seminar at an Asian Business Leaders Conference. The audience was made up of people who had attended top schools and achieved quite a lot in their careers. One speaker asked the audience to raise their hands if they were a leader. Only 10 out of 100 hands shot up. And the speaker said, “No, that’s incorrect. Every single person in this room is a leader. You should all be raising your hands.”

This exercise made me realize that we are all leaders in various ways. While we may not be the CEO of Apple, maybe we’re a community organizer, or maybe we’re good at organizing small events, or maybe we’re the leader in our family. Leadership is not black-and-white. It’s a spectrum, and doesn’t have to come with a title.

This was a very mind-opening experience for me. So while I am not technically an entrepreneur yet, I am an entrepreneur-in-waiting—collecting potential business ideas and gaining inspiration through continually meeting new people.

What helps you build confidence?

Chanting or active meditation helps me build confidence. I am a Buddhist, meaning that I chant and recite part of the Lotus Sutra every day. I’ve been practicing my entire life, and it has truly shaped my thinking, my vision, and even my character, for the better.

While I was in high school, I saw the true power of the practice of chanting, specifically Nam-MyoHo-Renge-Kyo. I suffered from chronic, debilitating asthma, meaning that I barely had the energy to smile, let alone walk more than 10 steps to the bathroom. Because of this, I often had to chant 7 hours a day to be able to breathe. Even though I was suffering so much, I actually felt fundamentally joyful. I was so happy to be alive, thanks to hours and hours of actively meditating.

After a few years of suffering from two-week-long asthma attacks, I began to chant with the utmost appreciation for the fact that I was able to breathe even a little bit, for the fact that I had extremely supportive parents, who sometimes chanted all night for me, and for being able to obtain all A’s amidst skipping school due to health reasons, and not having enough oxygen in my brain to remember everything I was learning. Even with the odds against me, I was able to overcome my asthma to the point where I could start running in marathons.

And boy did I run. I ran over a dozen half-marathons and one full-marathon by the age of 22. All of my strength and vigor was due to my years of chanting hours at a time to overcome my horrible asthma. I truly felt like I had made the impossible possible.

Before we end, could you tell me more about your mother and how she’s influenced you?

Yeah. There’s a good reason that my mother was a housewife—my Japanese grandmother worked long hours to support her husband who owned a small business, which was financially unstable. There was a lot of work to be done, so my grandmother wasn’t around the house a lot. My mother fundamentally didn’t want this for her own child, so she chose to stay at home.

Plus, to complicate matters, she decided to move to America at the young age of 26, with barely any English ability. And while she attended English language courses at San Francisco’s City College, she could only get hired for Japanese Language skills. Before she had me, she worked at a leather goods shop in San Francisco that catered to Japanese tourists. Then when I was in middle school, she worked at a Japanese travel agency based in San Francisco. And now, she takes care of elderly Japanese as a companion. But for the vast majority of my life, my mother stayed at home to take care of me.

And because I was her sole focus, she made sure that I would excel in school, by taking me to-and-from school, driving me to my jobs, extracurricular activities, and gymnastics games, making me breakfast, lunches, and dinners, and making sure that I did my homework and studied hard for tests. Basically, we joke now that she was a kind and reasonable Tiger Mother.

We have one ‘famous story’ of how she exemplifies being a Tiger Mother. Since my parents had very little money, I always attended free gymnastics lessons, dance classes, etc. that my mom found. And because we didn’t have money, my mom also wanted to make sure that I would attend the best possible elementary, middle, and high school in San Francisco.

But my mother was utterly disappointed when she found out that I got into a local elementary school with terrible ratings. So she decided to visit the San Francisco School Board every single day to ask about my spot on the waiting list for the best elementary school. On her 30th day of visiting the school, the administrator said, “Look lady, you’ve been coming here every single day, but there are 50 people ahead of your daughter. There is NO way your daughter is getting into this school.”

My mom glared, and slowly turned her head back to see who was behind her—no one. So she slowly turned her head back to the administrator, and said, “Well, where are they?”

And that’s how I got into the best elementary school in San Francisco at the time. That’s why I really admire and respect my mom for having the courage to stand up for me, and making sure that I got into the best elementary school, as it led me on a journey of attending the best public high school and university in California. If she had not done what she did, I don’t know where I would have ended up.