A century ago Kyoto was “The city that does everything first.” Today it is “the ancient capital” and “the city of temples and shrines.” Kyoto’s development of leading-edge technology however, continues today…

[M]ost of the literature on Kyoto concerns its history as imperial capital. That’s just part of the story, the part that brings tourists to its pay-to-peek temples and gardens. This capital, previously known as Miyako, was also renowned as a manufacturing center. Artisans working in metal, wood, lacquer, textiles and ceramics depended on the most finicky and demanding clientele imaginable: the imperial court and surrounding nobility. This upper-class filter allowed only the most skilled artisans to survive.

The highest quality, intricate deerskin- laced armor, swords and sword furnishings were produced in Miyako. Two items that travelers to the capital were asked to bring back for the ladies were sewing needles and kyobeni , or lip rouge, produced from benihana flowers; the finest of both came from Miyako. Lip rouge from other parts of the country just did not compare. Needles made in Miyako required eleven processes, and were superior in smoothness. Threads did not break when passed through the eye, and the needle itself did not catch on the cloth when passed through. This was important, since kimono are made from panels of cloth and taken apart at the seams for cleaning, then sewn back together again. Tansu , or chests of drawers, made by craftsmen of Miyako were especially airtight; when empty, if a drawer was closed, another would pop open from the internal air pressure. Miyako’s candles, the illumination of the era, were built up in layers, longer lasting and superior to others.

The list goes on. Miyako was the symbol of extra fine, painstaking workmanship, but most of this city’s history as taught to Japanese school children (and tourists) concerns emperors, warlords marching into the capital to gain imperial sanction for their conquests, and temples.

Fast-forward through the ten centuries during which Kyoto was the imperial capital (with one brief, unimportant interruption). The shogunate in the political capital of Edo gave way, the Meiji Restoration of 1868 took place as an act of what pro-imperial factions considered a reversion of proper authority to the emperor from a long line of shogunate usurpers. Now Miyako was not only the spiritual but also the political capital of the nation. Her residents were elated, exuberant, energized with new optimism — until rumors spread that the emperor planned to move the capital.

Precedent was a dark cloud hovering over those rumors: Moving the imperial capital was part of Japan’s history. It had been done routinely upon the death of each emperor until the attempt to establish a permanent capital at Nara in 710. This failed after seven decades in the face of Buddhist priests flexing non-compassionate political muscle. The emperor next moved the capital to Nagaoka, west of present-day Kyoto, and after a decade there amid natural disasters, scandals and an assassination, moved again in 794 to the village of Uda, now Kyoto.

Some months after the Restoration news came that the emperor was leaving on a journey. Post-Restoration joy in Miyako turned to protest. Citizen demonstrations against moving the capital filled the imperial palace. The emperor — rather the string pullers behind him — answered with an imperial denial: “I am going to Edo to change its name to Tokyo. I shall return.” This year is the 140th anniversary of the emperor’s promise. Kyotoites are still waiting.

After the capital was moved, Japanese and foreign scholars and writers largely forgot Kyoto, especially the real impact of the move on the people of the city: the economic base had been centered on the imperial court and nobility; now it was pulled away. Financially strong merchants followed the emperor to Tokyo or moved to other parts of the country. Kyoto’s population dropped sharply. One in seven homes was abandoned. The buzzword was “Only fools stay in Kyoto.”

Japan was reorganized from feudatories into prefectures, and the new Kyoto prefectural government decided to rebuild the city on the emerging technologies of the era. A training center was set up for developing new products. City Hall now stands where an agricultural research facility with a Dutch-type windmill researched new irrigation methods and new edible, marketable plants. Three Kyotoites went to France to study the new Jacquard looms, then imported the first of these in Japan into Kyoto. A center was set up to teach Kyoto weavers the complicated techniques, and Jacquard added new dimensions to Kyoto’s centuries-old brocade textile trades.

A Seimi Kyoku (from the Dutch-from- French term for chemistry) was set up to develop new, marketable products. Known in English as the Kyoto Prefectural Physics and Chemistry Institute, it was headed by the German scientist Gottfried Wagener. He came to Kyoto in 1878 with a long list of specialties, including chemistry, physics, photography, crystallography… Wagener taught European cloisonné and other techniques that boosted Kyoto’s ceramic trades.

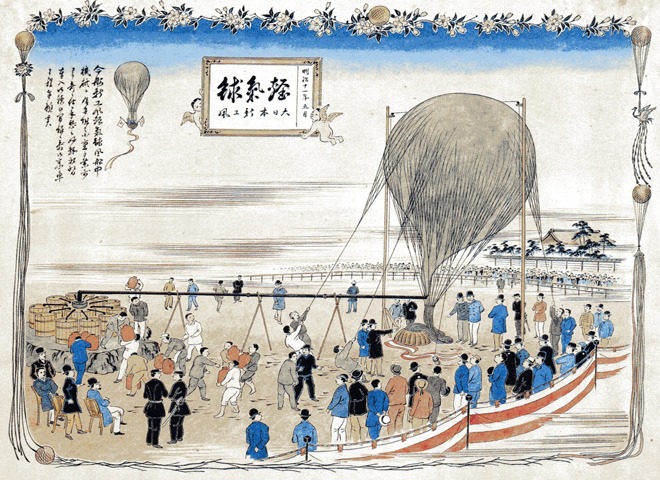

Wagener’s most enthusiastic disciple was Shimadzu Genzo, a metal craftsman fired up over the new sciences. The prefectural government wanted to stimulate scientific thought in Kyoto and hired Shimadzu to build a man-carrying balloon. It took off in the old imperial palace grounds to an audience of some 40,000 paying viewers. Shimadzu’s eight-year-old son was one of those impressed. He followed his father’s scientific lead and under the name Shimadzu Genzo II became one of Japan’s most important inventors, especially in the field of electricity. He produced Japan’s first X-ray photo just ten months after Dr. Wilhelm Roentgen discovered the phenomenon. Japan’s first medical X- ray equipment followed, and Japan’s first storage batteries and hydrostatic generator. Shimadzu produced the first book in Japanese on Western physics, and imported and sold scientific instruments. And Japan’s first lathe-equipped Western style ironworks was set up alongside a Kyoto river.

The central government in Tokyo sent students to different parts of the country to propose ways to build a new Japan. In 1881, 20-year-old Tanabe Sakuro headed for Kyoto, walked over the transportation barrier of the surrounding mountains to the east and envisaged cutting and tunneling through them to make a transportation canal that would bring the waters of Lake Biwa eight kilometers into Kyoto. The waterway would enable transport of larger quantities of supplies through the eastern mountains than could presently be carried by humans or horseback, especially coal needed to fuel industry, and would connect with an existing canal and river route from the center of the city to Osaka.

Kyoto’s main industry of textiles ground to a halt when the city’s Kamo River dried up in summer. Dyers needed a copious water supply to wash out fabrics and thread before subsequent processes could begin. In addition to providing a year-round water source, Tanabe’s plan would allow a mechanical power takeoff to drive Kyoto’s industries, especially in textile-related areas.

Tanabe took his canal proposal to the new governor in the prefectural office, then headquartered in Nijo Castle. The governor, recognizing the canal’s potential to reinvigorate Kyoto, gave his approval. Tanabe presented a complete plan based on his study of the excavation and tunneling that the project would require. But the Kyoto governor had to fight opposition in Japan’s central government led by a highly paid Dutch engineer; he said the plan was risky and should be abandoned. The governor won, and in 1885 construction began. This was young Tanabe’s graduation thesis, but he was hired by Kyoto prefecture as chief engineer for the project.

As the canal was nearing completion, news of hydroelectricity arrived. Tanabe embarked for America and studied a hydroelectric plant at Aspen, Colorado, where the head — the distance water drops to the turbines — was similar to what would be encountered in Kyoto. People moved fast then: mechanical power takeoff was ditched in favor of electricity. The canal was completed in 1890 and in the following year Japan’s first commercial hydroelectricity started flowing. Thomas Edison was 44 years old.

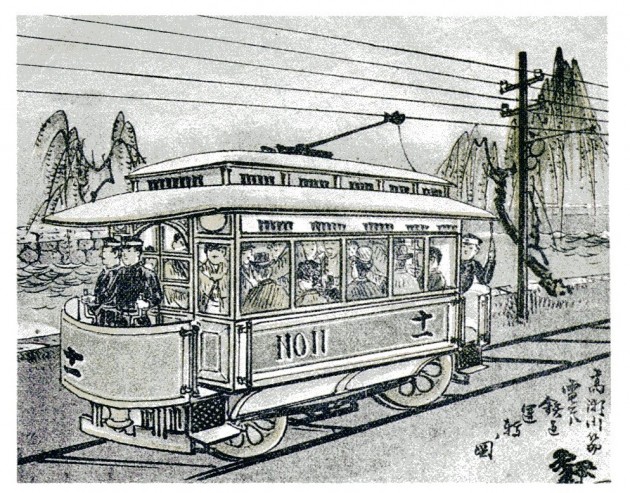

The electricity eventually powered Kyoto’s industries and gave the city’s kabuki theater Japan’s first electric stage lighting. In 1895 Tanabe’s hydroelectricity powered Japan’s first municipal streetcar system.

The electricity eventually powered Kyoto’s industries and gave the city’s kabuki theater Japan’s first electric stage lighting. In 1895 Tanabe’s hydroelectricity powered Japan’s first municipal streetcar system.

Kyoto’s leaders had foreseen that the new scientific industries would require an educated citizenry. In the spring of 1869, just months after the shock of Kyoto’s loss of capital status, the city had its first primary school. By the end of the year, more than 60 schools were functioning, again achieved against opposition. Much of the city, especially the Nishijin area, had been leveled from the fires of battles that led up to the Meiji Restoration. “Why waste money on education,” many said, “when there are more important things to consider, like our livelihood?” But the schools went ahead, and Kyoto beat by three years the central government’s establishment of compulsory education in Japan. Soon Japan astounded the world when it achieved virtually complete literacy, a rate the United States never has and cannot be expected to approach. Kyoto was the vanguard.

Today manufacturing holds about thirty percent of Kyoto city’s financial base, some half of which is in high tech. The high tech sector alone exceeds her tourist related businesses — hotels and inns, restaurants, food suppliers, transportation — which hold about ten percent. Several of Kyoto’s big techs firms are famous (Nintendo, Shimadzu) but most of her precision production is in secondary products — hidden components such as semiconductors, switches, circuits, screens, and production machinery. And this world, in the PR shadows of the city’s touted shrines and temples, is where Kyoto’s post-Meiji Restoration vitality carries on. When a Kyoto company startles the world with a technological accomplishment, cliché- addicted journalists usually cite the origin as “this city of shrines and temples,” a paradox to them. No paradox, but an information blackout of Kyoto’s Forgotten Era, when it pulled itself back from the dead with technology.

HAL GOLD (1929 ~ 2009), was a newspaper columnist, novelist, translator, shigin performer, actor, and beloved friend of KJ and a true Kyoto legend. A writer/translator with special interest in the post-Meiji Restoration era, Hal’s works include Neutral War (WWII historical fiction); Unit 731 Testimony (history); From Shanghai to Shanghai : The War Diary of an Imperial Japanese Army Medical Officer, 1937-1941 by Tetsuo Aso (trans); and ITALICS The Politics of Nanjing (trans.)