By Timon Screech

The core function of Kyoto, as concept, is evinced in its name: during the Edo Period (1603-1868), the name Kyoto was not used. In earlier times they had called it Miyako, but then people said just Kyō, though mostly the city was called Keishi, where kei means ‘metropolitan’ (the same character of kyō), and shi means ‘master’. As Japan’s capital, it inculcated into other cities how they should be. Edo (present-day Tokyo), by contrast, was often called Kōtō (‘Edo of the east’) or Kōfu (‘government Edo’). Edo was known as the ‘city of fire and fights’, Kyoto for its venerable temples and storehouses. If Edo had executive power, Kyoto had aura.

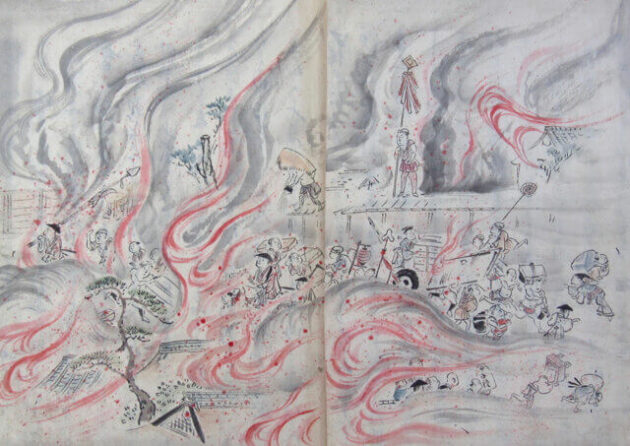

In the first lunar month of 1788, the loss of 90% of Kyoto to fire was therefore met with widespread dismay across Japan, with many eye-witness records of the event. Other large urban fires had plagued the city, particularly during the Onin War (1467-1477), but none to the extent of this oft-overlooked conflagration. Few visitors today notice that there are not more than 10 or 12 buildings pre-dating 1788 in the original city. These include Sanjūsangen-dō, the main hall of Shōkoku-ji, and the abbacy of Kennin-ji. The Great Buddha Hall was saved, though has since been lost. Older structures survived in the surrounding hills, and have now been incorporated into Kyoto as it expanded over time.

It was mid-afternoon on the last day of the month when fire broke out just east of the Kamo river and south of the small Donguri Bridge (located to the south of Shijō). By 6pm flames had spread as far as Teramachi, a thoroughfare containing many temples. By midnight it was at the Shimogamo Shrine. At 2am the Dairi (today called the Gosho, or imperial palace) was threatened; shortly thereafter the main enceinte (walled section) of the shogunal compound, Nijō Castle, was alight.[1] Rain fell, but it was not enough, and by morning 201 temples, 37 shrines, 36,797 common dwellings and a total of 1,424 city blocks in 20 separate locations were gone.[2] People from the surrounding regions swarmed to view the flames. One shogunal official later announced he had raced 20km in just two hours to witness the ‘metropolitan master’ taking its leave.[3]

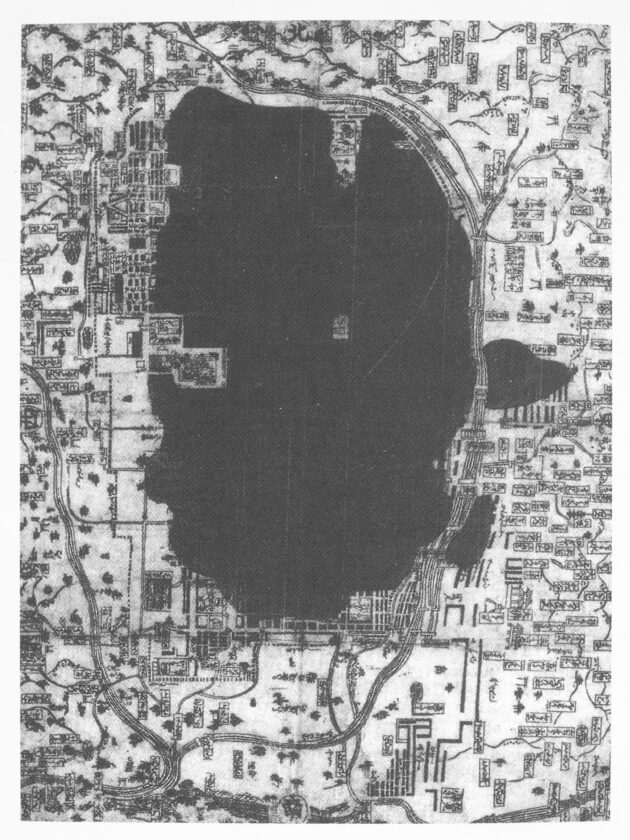

News spread quickly. At the farthest end of the land, the head of the Dutch East India Company’s Japan station in Nagasaki, Baron van Reede, recorded in his log, the ‘complete destruction of the great city of Miyako’.[4] The obliteration found its way into one of the first comprehensive books on the shogun’s realm published in Europe, Isaac Titsingh’s Illustrations of Japan.[5] Maps were sold showing the extent of the erasure so that all could assess the extent of loss.

A physician named Tachibana Nankei went about talking to people, appraising the toll in medical terms, including psychological. ‘Many’, he said, ‘were sent insane by the terror of their experiences.’ In such a time odd things occurred, and Nankei also came across a man previously been affected by lunacy, but who had been healed ‘by the extraordinary confusion going on around him… which seemed peculiar to me;’ but the freak cure only showed how logic was out of place, and that the doors of rationality were unhinged.[6]

The Great Fire of 1788 spawned much sustained writing. Dozens of the literate put brush to paper in attempts to come to terms with the tear in their culture’s fabric. A new genre of ‘fire diaries’ was invented. Those who experienced the eradication sought to salve themselves lexically, stemming the flow of pain with the ointment of words.

Fujishima Munenobu, a middle-ranking nobleman, dashed out with a writing kit thrust in the folds of his clothes, and spent the night tramping about, setting down when and where the flames were moving, and what, and how much was gone.[7] He gripped the obscenity of the facts with the precision pincers of place and time. Munenobu did not stop when the fire was out, unable to effect closure, and kept on writing until he found some external force to relieve him of the need to continue. He ended on the first day of the fourth month (mid-May), that is, the ritual day when winter clothes were swapped for spring ones, and the earth burgeoned again. Revested and with the flowers coming out, Munenobu could at last begin to think of his city reviving too. Others were even less sanguine, and Nankei, the physician, noted unbendingly that after the fire, the cherries blossoms ‘were never the same again.’[8]

Ban Kōkei was a furnishings dealer by trade, but also an ardent chronicler of Kyoto’s unique traits. He tried to sort through his emotions after the blaze by compiling strings of waka (courtly verse), expressing his horror via a controlling rhetoric that hummed with the tone of balmier days. Waka were rarely used to describe anything more brutal than lost love or the sadness of aging, but Kōkei compelled this etiolated genre to support ‘fire poetry’. He happened to be in the street when the flames struck, and he remained out of doors, seeing what he could, throughout the night. He returned exhausted and full of anxiety, to discover his own house was in the one unscathed part of the city. Kōkei wrote,

I returned home

Thinking, let me learn the news.

All was so hard to comprehend.

‘Would it have been the smoke that saved them?’

Sang the bush warbler.[9]

If Kōkei was spared, he nevertheless saw the night as one of visitation on all. He entitled the record he collated over the next weeks in two bathetic phrases, “The Wildness of the God of Fire: first ten-day period in the second month, eighth year of Tenmei [1788]” (Yagutsuchi no arabi: tenmei hachi-nen nigatsu shojun). Kōkei transcribed some of the better examples of other poets’ work. Many would be worth critiquing, but their shared trait is that they run fine language up against brutal fact. The appeal to the conventions of courtly writing only ironizes the mollifying power of verse. Two cases may be cited. One is an anonymous lament that rushes destruction against the gentleness of plum petals, which fell in the first month and were standard seasonal signifiers in waka:

Blow it back to its former colors,

You spring clouds!

It is the blossoming capital

That has now come fluttering down.[10]

The winds are asked to blow in reverse so that the tumbled structures of the city can sweep back, like leaves, onto the tree of state, restoring Kyoto to its pre-fire grandeur.

The other verse is by the famous poet Rōan, Fujishima Munenobu’s teacher. It became one of the most well-known of the ‘fire poems’, and Nankei commended its ‘overwhelming pathos’. Rōan wrote,

Look around this morning,

And you will see that all is a desecrated moor.

Is this burnt-out wasteland

Yesterday’s jewel-spread precincts?[11]

The verse uses a standard range of language, and is even conventional in its paralleling of the desert moorland and the stately city. By using the convention of a Japanese ‘pivot word’ (kakekotoba) in the third and fourth lines, the verse is tilted headlong into complete emotional collapse.

Another nobleman chronicler of the events was Machijiri Ryōgen. He was so unused to bustle or expedition that having been awoken from an early bed by rude bells, he was unsure how to react.[12] He began his record in the aloof idiom proper to his rank, but more or less immediately broke down as the narrative addressed the ravaged surroundings. At the opening, the reader is made to mistake the ruddy sky for a fine dawn, as Ryōgen says he did: ‘smoke and mist were of a soft red, feeling along the tops of mountains white with elongating cloud’. Ryōgen washed himself, combed his hair, performing his usual ablutions, and composed his mind quietly at his desk. He then left the writing table, and with it, forsook his poetic vein. Inversion hit him, his metre and the city. ‘Unsettled at heart,’ Ryōgen went into the street, where it looked to him as though stars were shooting upwards ‘careening from the surface of the earth’ towards the sky, and taking buildings and lives with them; ‘the clouds were so dark it was as if [my] ink had been splashed across the sky’. He could no longer write. There was so much to say, but no established way to say it.

Ueda Akinari responded in a similar way. For one of the foremost authors of his age, who had made a name for himself as a specialist in stories of the supernatural, set in a style known for its richness, his tack is intriguing. To recount the fire, he stripped down to plain terms, as if such truth required no studied language, and he wrote with uncharacteristic surrender, ‘the sound of screaming through tears, the sight of dashing about in confusion cannot be captured in any figure of speech.’[13]

For Ryōgen, the fire was caused. ‘What can the gods mean by this?’ he quizzed. Thinking back to the foundation of the city in the late-eighth century (the Enryaku era), he drew conclusions:

Remember, remember, and think how it was that the passing of generations have brought us to this point. The tsuberagi [emperor] of the Enryaku era moved the capital to this place, with mountains for its hems and a river for its girdle, erecting stout palace pillars – surely blessings enough to last one hundred million years! He laid out the city to conform to the geomantic diagram of the Four Beasts, to be a changeless abode for the teitaku [emperor]. How depraved times have become when a fire can break out even here![14]

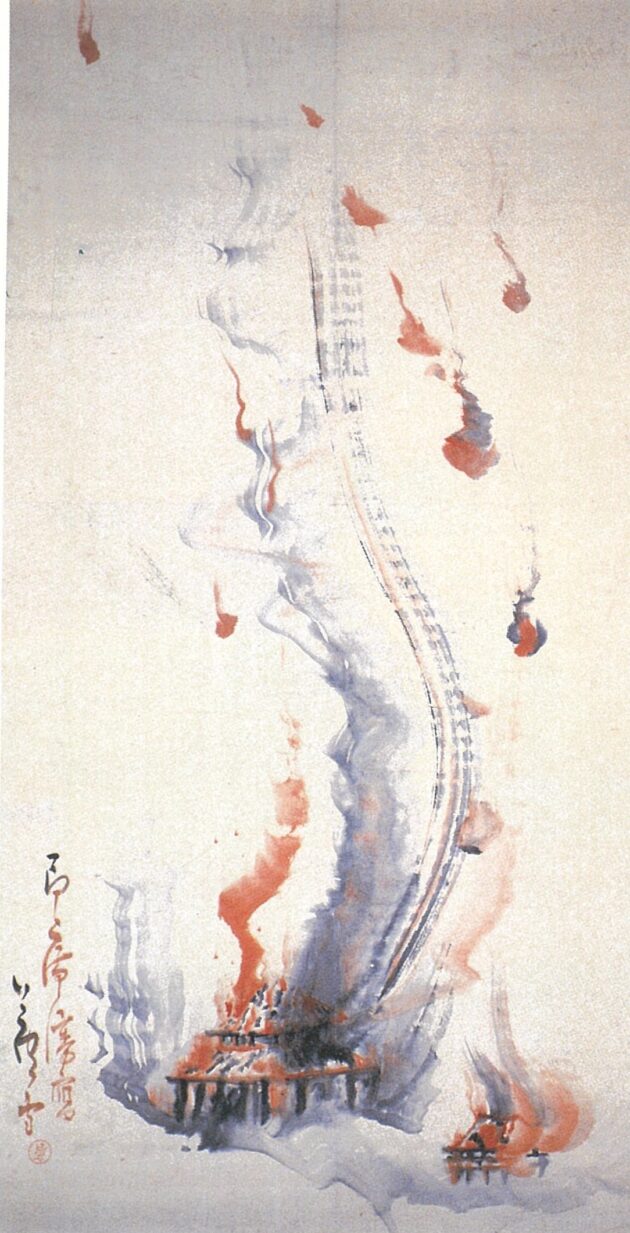

The incumbent emperor, in life called Tomohito but known to history as Kōkaku-tennō, was seventeen. He was not noticeably meritorious, and if not noticeably evil either, he could not but be implicated in the saga of decline. The preternatural quality of the fire was noted by all. Van Reede informed his East India Company superiors, ‘fire which normally burns only wood and fuel, even consumed iron and stones and made them explode and it even looked as if the stones themselves were spouting fire.’ Not unreasonably, he remarked, ‘people are considering this to be a great and extraordinary heavenly portent.[15]

The responsibility of the shogun and emperor was clarified in the damage done to their residences, but the latter was specially singled out: crowds looked on agog as a huge 2-meter fireball created, it seemed, by some divine hand and not emanating from the blaze itself, came flying through the air and landed precisely on the imperial palace, which was the end of it; Matsura Seizan, daimyo of Hirado, pondered this. He mused ‘where could it possibly have come from?’ but he certainly knew where it went: it landed plumb on the naishi-dokoro, that is, the imperial family’s spirit chamber.[16]

Tomohito decamped to the Shimogamo Shrine, which was the prearranged muster point in case of need. But his established locus of retreat was denied, for that too began to burn.[17] They then hurried to the Temple of Sagely Protection (Shōgo-in), across the Kamo river, well known to Tomohito since he had lived there as prince-abbot-elect, before an unexpected selection had made him emperor.[18] Complaining about his accommodation, the Emperor moved in with his father at the Temple of High Radiance (Shōren-in) until elaborate alterations were made at Shogo-in. These can still be seen today.

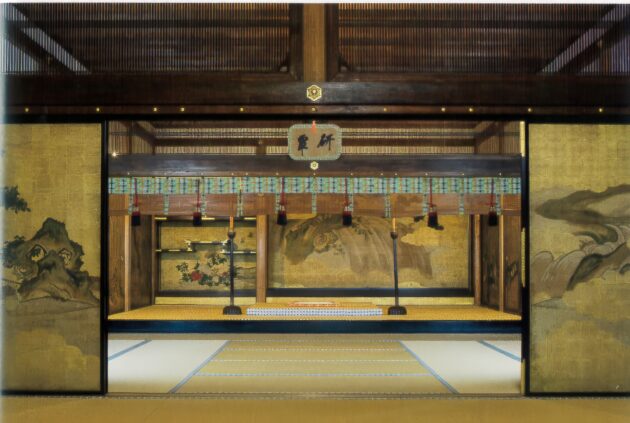

The 1788 fire was a devastating event and an indictment of the conditions of the realm. The Tenmei Period (1781-1789) is also known as a time of terrible famines. Yet neither shogun nor emperor were ready to let go. Tokugawa Ienari remained in post until 1837, and Tomohito until 1840. All the country’s fires resulted in surprisingly few changes in in architectural style or construction methods, but at least in Edo, the shogunate was experienced at dealing with the aftermath. Kyoto was soon rebuilt, close to how it looked before. Except in one regard: pernickety to the end, Tomohito kept on demanding a bigger palace, which he claimed was his due by historical precedent. Matsudaira Sadanobu [Figure 6], the shogunal chief minister, accepted this (he was a famous antiquarian), and one result of the fire is that Kyoto regained – and still has today, though in a later rebuilding – a revived Heian-style palace.

[1] This sequence follows Fujishima Munenobu, Tenmei taika no ki, in Kansei bungaku sen (Private Press, Kyoto, 1974), pp. 141-44.

[2] Fujishima Munenobu, Tenmei taika no ki, p. 154

[3] Yuasa Akiyoshi, Tenmei taisei-roku, Nihon keizai daiten, vol. 22 (Ōbunsho, 1927), p. 261; the original units are 5 ri in 1 koku 6 bu.

[4] Leonard Blussé (et al eds & trans), The Deshima Dagregisters (Leiden: Intercontinenta, 1996-97), vol. 9, p. 153.

[5] Isaac Titsingh, Illustrations of Japan (London, 1822), p. 101.

[6] Tachibana Nankei, Hokusō sadan, in his Tōzai yūki – hokusō sadan (Yūdōdō, 1913), p. 207.

[7] Fujishima Munenobu, Tenmei taika no ki, pp. 141-44; this is a section of his larger Munenobu no nikki.

[8] Tachibana Nankei, Hokusō sadan, p. 174

[9] Kaeri kite kiki mo sen ni some-tsukashiki kemuri no moreshi ya to no uguisu; Ban Kōkei, Yagutsuchi no arabi: Tenmei hachi-nen ni-gatsu shojun, in, Kansei bungaku sen (Private Press, Kyoto, 1974), p. 127.

[10] Moto no iro ni haya fuki-kaese haru no kaze hana no miyako mo chiri-chiri no yo; ibid., p. 133.

[11] Kesa mireba yakeno no hara to narinikeri koko ya kinō no tamashiki no tei; ibid., loc. cit., and Tachibana Nankei, Hokusō sadan, p. 202; Nankei’s phrase is kangai no amari.

[12] Machijiri Ryōgen, Tenmei uutsu kōki, p. 119.

[13] Ueda Akinari, Kyōto taika no ki, in, Kansei bungaku sen (Private Press, Kyoto, 1974), p. 138.

[14] Machijiri Ryōgen, Tenmei uutsu kōki, pp. 119-25.

[15] Blussé (et al.), Deshima Dagregisters, vol. 9, p. 155.

[16] Matsura Seizan, Kasshi yawa, vol. 1, p. 126. The original dimension is 3-4 shaku.

[17] City of Kyoto (ed.), Kyoto no rekishi, vol. 6, p. 64.

[18] For Tomohito’s childhood period at Shōgo-in, see, Fujita Satoru, Bakumatsu no tennō (Kōdansha, 1994), p. 47.

TIMON SCREECH taught at SOAS, University of London, for 30 years before moving to the International Research Center for Japanese Studies (Nichibunken), Kyoto, in 2021. He has published 15 books on the culture of the Edo Period, probably the best-known being Sex and the Floating World, and Tokyo before Tokyo. In 2016, his field-defining overview of Edo art, Obtaining Images, was paper-backed. Screech’s work has been translated into Chinese, French, Japanese, Korean, Polish and Romanian. He is a Fellow of the British Academy and in 2022 was awarded both the Yamagata Bantō Prize and the Fukuoka Asia Prize.