[K]yoto was Japan’s capital, though not always the actual seat of power, from 794 to 1869. In 1987 the city houses a population of 1,479,909 in 876,477 households and extends over an area of 610 km2. Spared destruction during the Second World War, it has become the largest open-air museum of traditional Japanese culture and town-scape. Tourism (37 million visitors in 1986) supplies close to a quarter of its income.

Although Tokyoites often call it furukusai (stinking of antiquity), Kyoto is a modern city, too. It has not rushed headlong into “Goodbye History, Hello Hamburger” development, nor has it become a dead urban museum. It has taken a middle way that allowed American historian John Whitney Hall to say: “Kyoto more than Tokyo forces upon us an awareness of the conflicts and tensions which still can be found in Japanese life, posing constantly the question of where Japan’s historical past fits into its modern present.” The municipality shows its own awareness of this conflict in setting “Tradition and Creativity” as the theme for the first World Conference of Historical Cities, to be convened here in November.

Of all cities in East Asia, Kyoto has the oldest and probably the strictest official preservation policy. In stages it has enacted planning legislation which in one way or another preserves close to three quarters of the municipal domain. The history of preservation in Kyoto, and Japan, can be viewed as a learning process, in which historic value has been assigned to loci of expanding breadth. It was initially seen to reside only in the isolated object, then in space as well (usually natural space around an historic object), and most recently in place — that is, the streetscape or urban district.

FROM OBJECT…

After three decades of working feverishly to internalize Western culture, Japan cast an eye to its heritage in 1897 with the Law for the Preservation of Ancient Shrines and Temples. Its scope was limited to landmarks in certain ancient Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples, objects which even today are the most numerous in national and local registers of tangible cultural properties.

That law and later object-preservation laws — for monuments and historic and scenic sites (1919), “national treasures” (1929) and artworks (1933) — were all replaced by the 1975 Law for the Protection of Cultural Properties.

Protection is extended to five categories of objects: tangible cultural properties (buildings, works of art and writing, archaeological specimens), intangible cultural properties (artistic skills), folk-cultural properties (objects and customs related to folk occupations, festivals or entertainment), monuments (historic and scenic places, natural objects), and groups of historic buildings. The Ministry of Education can elevate any of those locally designated items to the national register. They are then referred to as “important” cultural assets and qualify for national subsidies.

Buildings which are selected as cultural properties become eligible for government subsidies to help defray the costs of repair, rebuilding and maintenance. In Kyoto, a total of 384 buildings are protected in this manner (197 by the national government, 129 by Kyoto Prefecture, 58 by the city). The vast majority are shrine and temple buildings, and a few folk houses and Western-style buildings are included.

Kyo-machiya (typical Kyoto town houses), which are disappearing at an alarming rate, have so far received little attention in the movement to protect historically valuable buildings. It is estimated that in the 18th century 400,000 citizens of Kyoto lived in these beautiful structures.

Within the confines of Kyoto only three such townhouses have been selected, for preservation, one each by the national, prefectural and city governments.

…TO SPACE…

What is left of the original Heian-kyo, the “Capital of Peace and Tranquility” of 794, are not individual buildings, whole urban quarters or any social stratification, but an urban infrastructure in the form of the rectangular grid layout of its streets, and its overall placement into nature. These basic rules of structure and placement were learnt from Chinese urban geomancy. An idea) site for a city was to be: surrounded by hills and mountains on its northern, eastern and western sides; open to the south; situated on ground sloping slightly towards the south, and thus being transversed by rivers running from north to south; adjacent to a major river on its eastern edge; and guarded by a particularly prominent mountain to the northeast, in order to close the “devil’s gate”, the direction of evil influences. These few rules describe in the shortest possible manner the natural genius loci of Kyoto.

The effort to protect this crucial aspect of the historical urban artefact started in 1930 with a city ordinance creating Scenic Areas. About 34 km2 were designated, forming a horseshoe of open space around the city. In response to postwar pressures from suburbanization, this area was gradually expanded and by 1981 covered about 145 km2 (1/4 of the city’s total area). Besides the prohibition of any new development in that Scenic Area, any reconstruction, alteration or addition to existing buildings needs the advance permission of the mayor’s office.

More than half a century later it is clear that this enlightened conservation ordinance has been able to protect to a great degree the natural character of the city, and to stem uncontrollable urban sprawl. The Kyoto Urban Parks Law stipulated 6m2 of park area per citizen, a target which with 2.4m2 by 1980 had hardly been achieved. But this figure should be judged in conjunction with the huge, uncounted Scenic Area within easy reach from any point in the city. Another important effect of this policy was to guarantee that natural mountains would always be within the visual field of urban Kyoto. Looking east, west or north along Kyoto’s straight streets or avenues from any point in the city center, the untampered-with green mountains are always one’s eye-stop. Sometimes, shrouded in mist, they appear very distant; at other times, on clear days, they are close at hand. Together with the rectangular street grid they serve as orientation for the city as cultural artefact.

Kyoto is not only set like an urban jewel into a distant horseshoe of naturally wooded mountains. There is an internal setting as well, consisting in renowned historic spots, former palaces, temples and shrines, sites nested along ponds, streams or hills. These historic landscapes — man-made and much manipulated — guard the accumulated collective memory of many great literary figures, religious founders and amorous aristocrats. They are part of Kyoto’s cultural genius loci.

A citizens’ movement in the early 1960s prevented the construction of a private university campus on Narabiga-oka, amid one such famous historic landscape. Similar protests in Kyoto and other ancient cities gave birth in 1966 to the Special Law for the Preservation of Historic Landscapes in Ancient Capitals (mainly Nara, Kamakura and Kyoto). Supported by this national law, the City of Kyoto in 1967 designated as Historic Landscape Preservation Areas about 60 km2 of mostly large open green spaces, both natural and man-made, centering around important historical landmarks. As a planning tool this ordinance is so strict that so far no new construction has been permitted in these areas.

With this second layer of ordinances which protect the natural as well as the cultural landscape of Kyoto, the consciousness of preservation progressed from historical object to natural space, but still offered no recognition

to the city itself as an artifact worthy of protection.

…TO PLACE

Finally, in 1972 Kyoto turned its attention to machinami — traditional rowhouses or, in the wider sense of the word, urban streetscapes. The Visual Townscape Preservation Ordinance enacted by the city government in that year was the first Japanese legislation that brought protection to pieces of the urban fabric. This multifaceted law protected certain parts of the city as Aesthetic Areas; it restricted building heights in much of the urban core; and it authorized the creation of special areas to maintain the architectural identities of particular neighborhoods.

Eight Aesthetic Areas were designated within the central built-up city, five of them including major historic building complexes already selected as “important” cultural properties by the State. These are the Imperial Palace, Nijo Castle, and the precincts of the Western and Eastern Honganji and of the Toji Buddhist temples, amounting in all to 800 acres. The other three areas are huge chunks of traditional urban fabric to the east of the Kamo River and around Kiyomizu Temple, as well as a thin strip along either side of the river, totaling 1,500 acres. For these areas, the ordinance requires advance permission by the mayor’s office for any external construction work, and allows for the enforcement of strict controls over height (15 to 20m limits), external design and color.

More than half of Kyoto’s built-up urban core (approximately 15,000 acres) was designated by the 1972 ordinance as Areas of Special Control over Enormous Construction, in which the height of a new building is normally restricted to 31m. Any higher construction (50m is the absolute limit) requires the mayor’s approval with recommendations concerning external design and color. These restrictions were imposed as a negation, to prevent the recurrence of such eyesores as the Kyoto Tower (erected in the mid-’60s near Kyoto Station). They were also an affirmation of a consensus to preserve the whole city as such as a valuable historic place, and especially its characteristic of being visually dominated by the surrounding mountains.

As capital Kyoto was the headquarters not only of Buddhist sects, but also of many important arts and crafts industries. The traditional and, after World War II, modernized small and medium-size industries continued to flourish in some distinct neighborhoods, such as weaving in Nishijin, yuzen dyeing in Muromachi, ceramics in Kiyomizu, and sake brewing in Fushimi. These areas were and are characterized by a mixture of manufacturing and living in the same premises.

Recognizing the disintegration that had begun to affect certain of these areas, the city enacted ordinances to create the Haradani (1973) and Nishijin (1974) Special Industrial Zones, which have special zoning, volumetric and sunlight controls. These ordinances may indeed have promoted the small-scale traditional arts and crafts industry for which Kyoto has become famous, but they unfortunately did not contain provisions to preserve any of the traditional townhouses which reflect a unique and historic lifestyle.

Whole historic inner-urban districts or rows of traditional townhouses became eligible for subsidized protection under the 1975 national law that defined “groups of historic buildings” as a new type of “important cultural properties”. With the support of local residents, the city acted the next year to create the Sannenzaka Preservation District. Kyoto now has four Preservation Districts, and it is in these local areas, which are described below, that the city and the people have taken the most effective steps to define and to dynamically maintain those elements that create a sense of urban place.

DOMAIN OF GODS AND MERCHANTS

The whole eastern region of Kyoto known as Higashiyama has been rich in Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines since ancient times. Those sacred precincts with their linear accessways determined the original urban structure and historic development of the present Sannenzaka Preservation District (240 buildings on 13 acres).

Long before the founding of Heian-kyo in 794, a tribe named Yasaka no Miyatsuko, which had probably immigrated from the Korean Empire of Korai, had settled in the Kyoto basin. Their religious life centered around Hokanji, a Buddhist temple probably built around 589 and later destroyed by fire. Only the five-story pagoda is left (a rebuilt version from about 1440), the most important vertical marker in the neighborhood today. The street immediately below it runs straight to the main, southern entrance of Gion (or Yasaka) Shrine, probably the original sacred Shinto spot revered by the above tribe. The shrine’s festival, Gion Matsuri is to this day the largest and most important in Kyoto.

With its bright Vermillion south gate, Yasaka Shrine marks the unofficial northern entrance to the Sannenzaka Preservation District. Kiyomizu Temple, a complex of 17 buildings reconstructed in 1631, lies at the unofficial southern entrance. The district is a monzenmachi — a town before temple gates. Along its edge is Toribe-no, one of the two major burial grounds of Kyoto, which constituted the original city’s boundary between the worlds of the living and the dead. The fourth religious landmark, flanking one third of the precinct, is Kodaiji, a temple founded in the 16th century.

Due to its fine clay, this area along the Eastern Mountains, became a center for the still-famous Kiyomizu and Awate pottery in the Edo Period. A woodcut from 1787 shows the long-vanished wood-fired step-kilns built directly on the hill over Sannenzaka. The area is a literary landmark too, since the renowned poets Saigyo and Basho are reported to have lived there for some time.

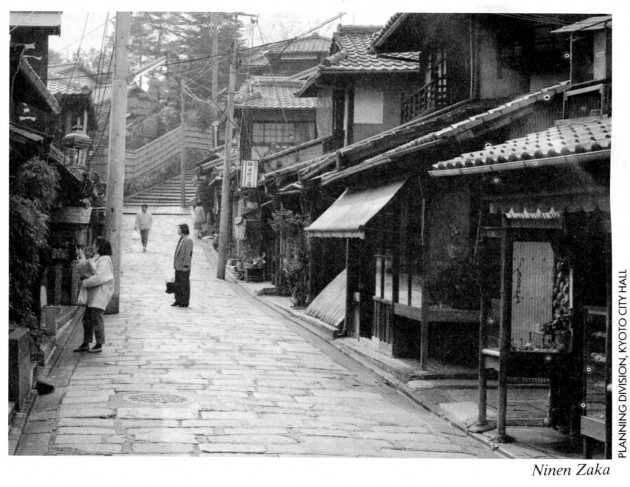

The “spirit of place” of Sannenzaka derives physically from its intersecting system of accessways that connect the main shrine and temples — winding and sloping paths, lined since ancient times with establishments purveying food, lodging, recreation and religious utensils. Culturally, the spirit of place derives from the area’s original quality as an ancient burial ground, from its later significance for the fine arts, and from the Kyoto-style townhouses which proliferated during the era of civil peace that began in the early 17th century.

The urban charm of this district lies in the different styles, sizes, textures, uses and colors of the houses which originate from different periods, a scenario which unfolds itself to the attentive visitor along the rising and falling, winding paths, like different settings on a picture scroll. The spatial experience of Sannenzaka Preservation District incorporates time, motion and association. Distinct from preserved European townscapes, the houses are small in scale and made of wood, with a life-span of about 100 years. Each reconstruction, repair or addition has come to reflect changes in lifestyle, and in the art of carpentry in Kyoto which is based on such design techniques as miegakure (alternately showing and concealing) and kurikaeshi, (rhythmic repetition of identical elements, or the setting of symbolic eye-stops along framed vistas).

Among the influences of the Osaka World’s Fair in 1970 was a realization on the part of the Japanese that their big cities had hardly retained any of the quiet atmosphere of traditional townscape. The few surviving examples were mainly in Kyoto, where a group of citizens living in Higashiyama founded a “union to protect the paths of Higashiyama” in order to find ways to preserve traditional family property and history. At that time the Sannenzaka area could already count 10,000 visitors on Sundays and 3,000 on weekdays. The city found that over 30% of the local residents expected to respond to this new influx of tourists by repairing or rebuilding their shops, and felt that an official preservation plan would be necessary to prevent rapid deterioration due to increasing commercial use. Based on this citizens’ initiative, the Sannenzaka District was designated as a municipal Preservation District of Groups of Traditional Buildings in 1976.

Right from the start the preservation plan did not envisage total restoration. Instead it established mechanisms for consultation, architectural guidance and financial support which are activated when an owner seeks a permit to build, rebuild or repair. Facade treatment is expected to conform to one of five specified types. Besides height and roofing restrictions, the preservation plan does not impinge at all on the spatial design behind those traditional facades. To get rid of existing eyesores and restore the integrity of specific architectural ensembles, the district was split into strips of 30 to 50 meters which represent coherent styles.

Architectural conformity is maintained through persuasion, based on a consensus that preserving a sense of place is desirable. The situation requires owners, builders and city officials to acquire deep understanding of the architectural traditions. Since the preservation district was created, the Sannenzaka area has gained in overall attractiveness with each addition, repair or reconstruction. The ever-growing flow of tourists increases business chances, yet despite its commercial success the area has remained a desirable place to live. In the last decade only two percent of the properties have changed hands, while two thirds of new construction has been residential. An interesting side-aspect of the designation of Sannenzaka is that the local citizens, their architects and carpenters had to reacquire various methods of traditional wooden construction which were about to disappear.

THE PLEASURE QUARTER

The preservation of urban districts is admittedly the last and most radical stage of protecting cultural properties, since it allows the state to regulate the appearance of private property for the assumed benefit of a larger community. In Japan, this intrusion onto private territory is mitigated by government financial subsidies, which underwrite part of the construction costs for street facades in preservation districts after the designs are approved by the authorities. The initiative for any repair or construction remains with the individual owner, who usually bears most of the cost. Furthermore, while the external appearance may be regulated down to the tiniest detail, the use and design of whatever lies behind this facade is up to the owner. (The first and largest nationally designated preservation district, the old station town of Tsumago in Nagano Prefecture, is the only place in Japan where design controls and financial subsidies apply to the building as a whole.)

In the Gion Shimbashi Preservation District of Kyoto, this “facadism” attitude may one day lead to a streetscape of traditional Edo-period ochaya (teahouses) walls camouflaging a series of typically modern downtown facilities such as clubs, bars, shops and homes. In fact, one site in this district has just been rebuilt — behind an authentic two-story ochaya facade — as a four-story boutique with basement and skylights.

Gion lies near the Sannemzaka district, in the Higashiyama region which was in ancient times, and to some extent remains, a kind of popular heaven full of pilgrimmage sites that correspond to the beliefs of the common people of the entire nation. Both of these preservation districts developed as monzenmachi, or profane quarters beyond the gates of the sacred places, catering mainly to pilgrims and tourists. Gion in particular has long been a rakugai ( outer city) abounding in teahouses, inns and amusement facilities.

The pleasure-quarter heritage of Gion dates back many centuries to ritual prayer dances and acrobatic entertainments which were performed on the shifting flood plains of the Kamo and Shirokawa Rivers. The 17th century was marked by the appearance of many small performance stalls for kabuki theatre, and of teahouses, at first serving only tea (mizuchaya) and later adding sake (ochaya). The buildable area was greatly expanded around 1670 by flood-control dikes, and a full-blown theater district with numerous teahouses came into existence along Yamato-oji Street. From 1712, the ochaya of Gion were licensed for geisha performances (in contrast to the geisha of the now-defunct Shimabara district in western Kyoto, the Gion geisha have never been prostitutes).

The present-day Gion district, from Shimbashi in the north to well south of Shijo Street, took shape after a devastating fire in 1865. The several entire blocks of traditional machinami which are still to be seen south of Shijo depend on the voluntary policies of the landowners, since publicly administered architectural controls (aside from the 15 to 20-meter height limit) apply only in the much smaller Gion Shimbashi Preservation District along the Shirakawa River to the north.

Both sides of the Preservation District’s main Shimbashi Street are lined with attached, mostly two-storied ochaya. The visual impression is one of strong unity created by variation of type. The facades are characterized by degoshi (slightly protruding wooden lattice windows) and noren (cloth-hangings decorated with family crests over the entrances) on the ground floor, and on the second floor by slender veranda railings which may be partly hidden by a row of oisudare (light reed or bamboo screens) moving and lightly banging with the slightest breeze. The thin membering and delicate proportioning of those lattices, railings and screens produce the much-admired elegance of the ochaya of Gion. Another continuous row of two-storied ochaya edges onto the south bank of the Shirakawa River, while the north bank is planted with willow and cherry trees.

Three footbridges over the small river allow graceful access to the teahouses. A small shrine with vermillion gate and fence at the bifurcation of the two streets provides the visual and religious focus of the Shimbashi neighborhood.

Since olden times there had been a silent consensus among the owners in this district not to allow any structures which are not in harmony with the architectural character. The intention of one owner on Shimbashi Street to replace his traditional ochaya with a four-storied concrete structure in 1973 aroused a citizens’ opposition movement, which found strong echoes among scholars, historians and city planning officials. After a building survey, the city placed the district under special protection in 1974 and created the Preservation District in 1975. National designation followed. Since 1976, under architectural guidelines for seven distinct types of ochaya facade (one in a set-back mansion style and the others of townhouse type), the city has approved and subsidized 62 repairs, 18 restorations, three installations of firefighting equipment and 59 replacements of hanging sudare screens.

RETREAT FOR LITERATI AND ARISTOCRATS

The shortcomings of a preservation policy protecting only facade, roof-form and height for a limited depth (30m at most), are becoming obvious, especially in Gion Shimbashi. Too often the careful and costly preservation of a traditional street view is marred already by high-rise structures that are situated outside the protected area, yet which easily intrude on the visual field. This problem seems unlikely to occur in Kyoto’s third protected monzenmachi, the Sagano Torii no Moto Preservation District, a rustic, linear village in the foothills.

Since ancient times the Sagano region northwest of the city, has been known as the locale of many of Kyoto’s famous scenic spots: Hirosawa and Osawa Ponds in the east, Mr. Atago in the north, Daikakuji and Tenryuji in the west. It is dominated even now by farmhouses, rice paddies, rows of traditional townhouses and occasional bamboo groves. It has never been the stage for any great political events in the tumultuous history of Kyoto, but was a place the literati have loved and praised since ancient times. For them Sagano did not just present a beautiful landscape, but projected the images of Japan’s great novels, as well as the emotion of their authors.

In the Shin-kokin-shu, a waka collection of the Heian Period, eleven poems refer to the darkness of Sagano’s autumn and winter seasons, and sing of Ukiyo no Saga (“the floating world of Saga”). With the establishment of a second burial ground for northern Kyoto in Sagano, the area came to embody the evanescence of all worldly desires. In Heike Monogatari, it is the setting for episodes of lost love and hermitage. Sagano appears in Noh chants of the Muromachi era amid evocations of the “mysterious darkness” of Japanese medieval courtlife, or as a windswept, ghostlike winter scene. The haiku of Basho, who moved there in 1691, portray Sagano as a place of bamboo thickets, persimmon trees and thatched huts for retreat. Tourist guides list some 40 sites that have been impregnated by classical literary allusions.

Today the residents of Sagano are engaged mostly in farming, forestry, fishing and, in the upper area around the temples, catering for pilgrims and tourists. Despite the postwar increase in tourism, more than 80% of the inhabitants expressed complete satisfaction with their environment in a 1976 survey. This love of place is best visible in the community’s cooperation each August 16th for the okuribi, or “sendoff fire”, one of five kindled around the city during the bon festival to guide ancestral spirits home from their annual visit to the living. The huge fire built on Mandala Mountain above Saga is in the shape of a Shinto gate or torii, hence the name Torii no Moto, “at the base of the torii”.

The place-experience along the 600-meter-long Sagano Torii no Moto Preservation District is marked by the curves and changes of grade along the path, by the architectural quality and use of the houses, and by the major landmarks: a group of wayside stone Buddhas, the Nembutsu Temple beckoning from atop a long bamboo-shadowed stairway, and the bright torii of Atago Shrine.

To frame a valuable preservation policy for this essentially sequential space, the city’s 1976 survey report interpreted it as a series of 24 “vista units” (visual fields about 30 meters deep), set off by “vista frames”. Five types of vista are identified, containing the basic elements of the sky, the road, fences, trees, and house fronts. This principle lent rhythm to the entire street, with mountains providing a constant and distant backdrop. The combination of facade preservation, the unique sequential visual pattern, and concern for the maintenance of traditional lifestyles resulted in a sophisticated preservation policy for an environment that is both historical and alive.

MAIN STREET

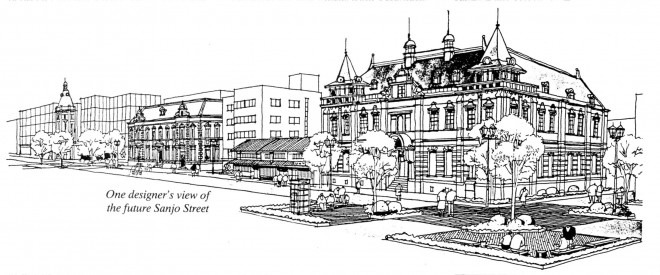

As one end of the old Tokaido Road between Edo and Kyoto, Sanjo Street was originally lined with shops and small Japanese inns. In the late 19th century it became the “main street” of Kyoto with various Western-style buildings of brick, stone or concrete. This reflected the Meiji-era impulse to adapt Western technology, as well as Kyoto’s vigorous leadership in doing so. Along Sanjo were located the major banks, schools, post office and newspapers of the city. By now they have mainly moved to more prestigious plots on nearby streets, but some of the buildings remain, interspersed with a number of traditional wooden buildings with machiya-type facades.

One of the Western buildings, the Kyoto Branch of the Bank of Japan built in 1907, has been designated a nationally “important” cultural property, and two others, the Mainichi Shimbun office (1929) and the remaining portion of the Nihon Seimei Life Insurance Co. (1915), are listed as cultural assets by the city. In the name of preserving the area as a showcase of Meiji- and Taisho-era urban design, the city created the Scenic District of Western Historic Atmosphere in 1985. It covers 30 meters on either side of the street for nine blocks from Teramachi to Muromachi Streets, although the surviving Western-style buildings are found only in one two-block zone and on two other intersections.

A permit from the mayor is required for any construction or alteration in the three critical zones, and for a new structure exceeding 10 meters along the entire district. The city subsidizes up to two-thirds of the repair costs and half the restoration costs for facades of important Western-style buildings as well as traditional wooden structures.

This preservation effort is admirable and understandable, but what has so far been overlooked is any provision to restrict automobiles on a street with no sidewalks, along which even walking — much less enjoying the architecture — is practically impossible.

The national or international community of practicing architects may not be perfectly happy with the attitudes embodied in these preservation districts. As one critic asks, “Will the slavish reproduction of the past deprive us of the landmarks of the future?” From another angle, “Will demands for cosmetic compatibility betweeen old and new unintentionally devalue the existing buildings by denying their uniqueness?” On the social level, a fundamental question can be put: Is the architectural freezing in time of a whole neighborhood — its “condemnation” to an existence as a public urban museum — a legitimate right of local and national government? In Kyoto, a deep sense of tradition and a vital tourist economy have, happily, coalesced into solid support for preservation policies that are both broad-ranging and selective.