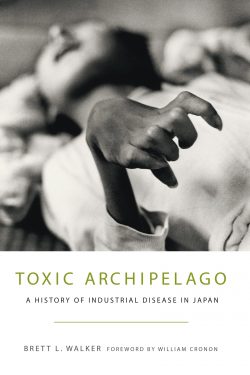

Any student of Japan who is tempted to idealize, or simplify, the way people in this country have historically interacted with nature would do well to search out the writing of environmental historian Brett Walker. History as Walker writes it is as seamlessly complex as life outside of books. He treats economics, folklore, ecology, family history, and politics not as independent disciplines but as threads that wrap together into episodes, which in turn accumulate into the patterns that give history meaning. As he acknowledges—without apology—in the prologue to his most recent book, Toxic Archipelago: A History of Industrial Disease in Japan, the patterns he finds are often dark ones: “I am a historian and I am calling it as I see it, and I see environmental decline and deterioration everywhere,” he writes. Yet it is industrial civilization as a whole, rather than a uniquely Japanese interpretation of it, that his books condemn. Walker says he “stumbled on Japan” as an undergraduate history student in Idaho. After graduating he traveled to Hokkaido, teaching at a juku and falling in love with the country. While there he befriended some scholars who encouraged him to study its history more seriously; he did so, gaining his Ph.D from the University of Oregon in Japanese history in 1997. Since then he has documented how trade and conquest transformed Hokkaido’s landscape (The Conquest of Ainu Lands: Ecology and Culture in Japanese Expansion, 1590-1800, 2001); how modernization drove wolves to extinction (The Lost Wolves of Japan, 2005); and how workers, farmers, mothers, and babies have paid in pain for the industrial development of Japan (Toxic Archipelago, 2010). Always, the stories he tells are unflinching, impressively researched, and eloquently written. Often, he traces the roots of environmental destruction much further into the past than we commonly assume they reach.

Walker is Regents’ Professor and department chair of history and philosophy at Montanta State University, Bozeman. Winifred Bird spoke with him by telephone at his office in Bozeman.

Winifred Bird: Your article about the Hachinohe Wild Boar Famine describes an episode in far-northern Honshu in the mid-1700s, where farmers started growing soybeans as a cash crop to send to Edo (now Tokyo), and to do that they used slash and burn agriculture. That inadvertently expanded wild boar habitat and led to a boar population explosion, which in turn led to competition for food and eventually a famine where 3,000 people died. What made you want to look further into that story?

Brett Walker: Well, I liked the story for a handful of reasons. The first thing that’s important about it is that when we think of commercialization, development, and environmental change, we oftentimes assume—wrongly—that those are products of modern life and industrialism. This tale offers us a cautionary note that we have long been impacting the environment in a variety of ways. The agricultural transition happened around 10,000 bce (before common era) with a massive restructuring of the way that we interact with the land. Any time civilizations develop the land for one reason or another you’re going to see environmental change. When we talk about Japanese environmental problems we tend to focus on the big modern cases like Minamata disease[1] or itai itai byou,[2] but what I liked about this story is that it shows that even earlier there were signs that proto-industrial, protocapitalistic growth of the Japanese economy was having an effect on the natural world. The second reason I like it is it illustrates an important point about how the Tokugawa political system[3] had started to get into a serious coreperiphery structure. There was the emergence of very large cities like Edo that were becoming massive consumer centers, but large urban centers have to have agricultural surplus, and where is that surplus coming from? As those cities spread, not only were they consuming agricultural land, but the farmers that were near those cities had started to grow mulberry leaves for sericulture and other cash crops and they were not really interested in growing food for urban inhabitants. So places like Hachinohe, which had been pretty removed from what was going on in Edo, started to get incorporated into an economic coreperiphery relationship. It’s a small-scale example of the kind of third-world-ization process that’s happened, writ large, on the planet. Some metropolitan industrialized societies—Japan would be one of them—consume resources that are developed and extracted elsewhere, and I think that was happening on a smaller scale in Japan [in the 18th century]. This led to environmental degradation in these peripheral areas. The third reason I like this story is because it involves wild boar, and Japan has this long, vexed relationship with inoshishi. The situation where a famine was actually caused by a bunch of wild boar caused me to look at eating practices, cookbooks, and historical relations with wild boar, how they figure in Japan’s culture.

You mentioned how in that era a core-periphery relationship was developing. I recently read an interview in the Asahi Shimbun with folklorist and scholar of the Tohoku region Norio Akasaka, who traveled through that area after the tsunami. He said that in some ways the region still resembles a colony of Japan’s centers of power.

A lot of people talk about it in that way. Certainly when Toyotomi Hideyoshi[4] began the process of unifying the country Hachinohe was almost an independent territory. You can use words like frontier expansion or centralization, but increasingly historians are using words like colonization to describe the process by which those unifiers brought Hachinohe into the core. I think with the tsunami and the nuclear mess you see that playing out. A colleague of mine, Christine Marran, has a great blog post on this, and one of the things she stresses is that you need to understand where this stuff happened. Tohoku is quite removed from a lot of the things that we think about when we think about Japan. It’s very rural, it’s pretty poor, most of the young people have moved out. A lot of elder fishers and farmers live there. I think this demographic social context is part of that longer history of the Tohoku region becoming a periphery.

The Wild Boar Famine occurred in the Edo period. I feel like there’s a trend to romanticize that era as a time of harmony between humans and nature, but in your work you often seem to trace the roots of industrial problems and exploitation of the environment to that same period. Was it a turning point in Japan’s environmental history?

I certainly don’t romanticize the Edo period. One of the things historians, particularly environmental historians, are wrapping their minds around is that any time we develop an economy or trade things, make things, buy things, sell things, we are interacting with the environment. We are extracting resources, so when you’re talking about premodern proto-industrial economies you’re talking about ways and modes of interacting with the natural world. Tokugawa Japan had a very sophisticated economy, there were lots of goods and services being moved around the country, it was national in scope, so it stands to reason that there’s going to be environmental consequences. It’s important to note that even though you have episodes like the wild boar famine—which certainly for people in Hachinohe was a great hardship— they still pale in comparison to the kind of problems we face in the modern world. But I firmly believe that the Japanese do not have a special relationship with the natural world. They have pieces and elements of the culture that celebrates the natural world—from gardening to poetry to you-name-it—but they also have cultural elements that are significantly less benign, such as an unbridled belief in the promise of technology and industry. Like all peoples on the planet, Japan has a complicated relationship with the natural world that’s shaped by religion and economic behavior and political practices, but certainly the notion that the Japanese enjoy a greener national philosophy is misguided. It does not hold up to historical scrutiny. The evidence for that is very clear. Even though Japan has done a good job in the modern period of tackling some of the big environmental problems— clearly there’s less mercury in the water than there was, and the air in Tokyo is cleaner, so there have been real advances—but in large part those are just technological fixes. The notion that Japan is becoming an ecologically modern country has been largely contingent on its ability to export dirty industries. So yes, the Japanese are not cutting down their own trees anymore, but that’s not to say they’re not cutting down trees somewhere else. For every electronic gadget and computer manufactured in Japan, copper, lithium and other kinds of fairly dangerous metals are mined somewhere. Japan has done a pretty good job of cleaning up at home but it still participates in a global story. When you start talking about environmental problems in the modern period you’re talking about things that transcend the nation state and its boundaries, politics, and culture. Global warming is not Japan warming, but rather it’s global warming. It means that the activities of a handful of industrialized nations are affecting the climate worldwide.

You said some of the positive trends are just technological fixes, but there’s an underlying something that hasn’t changed. How do you see the Fukushima accident fitting into that history of Japan’s relationship to the environment?

For me the way it fits into a longer trajectory, quite frankly, is just the complete and utter engineering of the Japanese environment. This is slightly exaggerated way to phrase it, but the Japanese islands are almost mechanical. If you look at a map of Japan, a satellite photo, very little of the coastline is not geometrically shaped. Much of the coastline has been reclaimed. It’s got tetrapods that prohibit coastal erosion. I think there’s one river left in Japan that’s still free-flowing, without a dam on it. Most have been transformed into cement chutes. Most of all the viable ports have been completely engineered and manipulated. Japanese towns have been built in areas where historically it was never a good idea to build because they’re floodplains. Cities have been built behind massive seawalls. The Japanese islands are very engineered places. In large part that’s because there’s not a lot of land so people have to make do with what they’ve got. But when we all watched images of the tsunami raging across Sendai and other places, what stuck out—at least to my mind—was the way that water interacted with the engineered landscape. We never talked so much about what it was doing in Matsushima, where you have a more or less natural landscape, just north of Sendai. What we did was watch it go into irrigation canals and onto rice fields and into plastic greenhouses where vegetables were being raised. We watched it sweep across ports and marinas and on top of roads and apartment buildings. We saw it sweep away homes and go over levees and crush seawalls. The interesting question about the tsunami is, when did that natural disaster become a man-made disaster? Certainly you could argue that the moment that wave, traveling at whatever, 400 miles an hour across the ocean, the moment it came on shore this became very much a man-made disaster. The ways in which that natural force behaved were shaped by the engineering, development, and economic priorities of the Japanese people. I’d say that fits into a longer trajectory of hubris, in the belief in the power of technology. What will happen as a result of this is not a disillusionment with nuclear power, or a disillusionment about building settlements in coastal floodplains— it’ll be a belief that we need to build a safer nuclear power plant and that we need to build a higher seawall, and that’s where I think the mentality hasn’t changed. But I don’t want to single out Japan in this respect because it’s not alone. I don’t think we’re talking about a particularly Japanese characteristic here. I think we’re talking about more of a modern characteristic.

Changing the subject a little, in Toxic Archipelago, you talk about visiting the sites of a number of Japan’s industrial disasters, and you yourself are constantly present in the book. There’s a passage where you talk about following monkeys around at the Ashio copper mine and[5] another where you’re watching a crab crawl out of a canal at the Chisso factory in Minamata. Those moments really caught my attention. What, as a historian, do you get from visiting these sites? What’s it like for you to be there?

It’s really hard to talk about how much I gained from going to these sites, talking to people, looking at the mines. When I was at Ashio, I was a bit of a scofflaw, hiking around areas where you’re not supposed to go, spelunking in empty mine shafts which is probably exceptionally dangerous, but it really opened my eyes to that world. A lot of the big mine shafts have been cemented over and closed up, but these hand-hewn mine shafts that were done in earlier times, the tanukibori, are scattered around the mountains. It was a good way for me to see and touch physically what this human impact on the environment looks like. In Ashio many of the mountains are still denuded because there’s so many poisons on them from the smelting process. It’s hard to write about that without seeing it. I also think it gave me a perspective—especially following the monkeys around Ashio—on the vibrancy of the environment. We have these definitions of a pure pristine wild environment that we somehow ruin with our technologies and our industry, but it reminded me that what emerges from humanity, our industry and the preexisting landscape is a kind of hybrid. You’re hiking to old mine shafts and you have troupes of Japanese macaques and trees are growing back through the foundations of old lodges where miners used to live. It was a very interesting place. It was almost like I was walking through the ghostly remains of an ancient industrial civilization that had disappeared and been replaced by monkeys and trees, but I had to continually remind myself that in fact that industrial civilization has not disappeared, it has just moved on. The crab at Minamata reminded me of the manner in which designers and engineers conceived of the Chisso plant, as almost a kind of machine, it was so carefully engineered. It had waterways that were shunting the poisonous water from the plant back into the Minamata Bay, and somehow it was all self-contained. But of course when I was there, even though the Minamata River is completely in a cement chute, and cement channels surround the Chisso factory, everywhere I looked there were crabs crawling out of the channels, seagulls flying into them. I realized that even in our best attempts to control nature we are never able to fully do so because nature has an agency of its own. The crab is going to do what the crab wants to do. That crab could be one organic pathway whereby poisons leave this highly engineered space and enter the broader food chain. It’s a small example but it made so clear in my mind the innumerable ways that could happen. To listen to these engineers talk, “well, we’ve got these technologies for cleaning these poisons, we’ve got this, we’ve got that,” illustrated how little they understood in some respects the vibrancy of the world they were living in. You go there even today and these engineered spaces are alive with active things that simply are not part of our plan.

At the end of that book you say you’re going to end on a hopeful note, and then you say, “even as the environment collapses under the feet of Homo sapiens industrialis, it will expose moments of profound beauty,” and that gives you consolation. To me that was really a heartbreaking thought, and it’s interesting that you see it as hopeful. Could you describe one of those moments?

First of all, to contextualize that, part of it was born from an impatience with the way we constantly are writing about environmental problems. Often, even people who write about environmental problems have an optimistic streak that’s shapedby the belief that “well, we can still do this. We can still eat the way we eat, live in the cities we live in, fly in the airplanes that we fly in, we just need to develop the technologies that are going to enable us to do it. We need to be more efficient, we need to be leaner, but we can still somehow live in the civilization that we live in.” I’m not so sure that’s true. Between the time that book was started and finished, the population of the planet had virtually grown by a billion. We’re now at about seven billion people and there’s no signs that’s going to stop. I know the Japanese aren’t necessarily contributing to that because Japan’s in a kind of demographic stasis, but again it’s not so much about the sheer number of people it’s about their ecological footprint, how much they’re consuming and Japanese, like Americans, consume more than their fair share. So I looked around at these problems and the way people talked about fixing them [with technology], while there’s no real discussion of what the carrying capacity of the planet is, and I started to realize that maybe we as a species are incapable of stopping this. Maybe there are forces at work that we’re just not all that capable of stopping. It also involves global politics. Environmental problems are often operating on a global scale, so they require a kind of cooperation that is not yet achievable. The US and Japan might be able to come to some agreements on this and that, but big transnational agreements on greenhouse gasses have been elusive. We simply have not been able to come together. That’s happening in the face of what is clearly growing climate change, and growing pressures on the landscape to produce more food. I didn’t want to come across like I somehow think we’re doomed, because maybe we’re not. We’re a pretty resilient species and maybe we will find ways to organize ourselves and transform the ways we interact with the landscape. It’s going to be Herculean because we’re not a very long-term-looking species and we’re talking about things that are happening over the course of generations of human beings, and we’re just not good at that. [But] in the midst of that struggle against our own natures, we are capable of acts of beauty. There’s the story of those orca[6] that washed ashore in Hokkaido—people talk about the Japanese today as being cruel dolphin-killers, but in this context, here are these people in Kushiro doing everything they possibly can to save a pod of killer whales. Risking their own lives to try to get to them from behind this ice-floe. It’s pretty clear now that those animals had been poisoned, that they had birth defects as a result of toxins in the environment and that’s why they got into the predicament they were in. There were touching descriptions of Japanese going out there, of how one photographer found a female orca trying to protect her calf. Those were incredible images. Or the famous image of the mother bathing her child in Minamata,[7] the image that W. Eugene Smith took. Those are very powerful images that come from ecological collapse. They come from this context. And so it’s not wholly ugly. We are not a wholly ugly species. Maybe in those acts of compassion and beauty, if we look deep enough in them, maybe we will find some of the answers for getting out of this crisis.

[1]In the early 1900s, Chisso Corporation’s fertilizer and plastics factory released organic mercury into Kyushu’s Minamata Bay. The poison became increasingly concentrated as it moved up the food chain from plankton to fish and shellfish, finally reaching the bodies of local fishermen, women and even their unborn children, causing a debilitating and excruciatingly painful set of maladies dubbed “Minamata Disease.” Some victims only received compensation from Chisso after a decades-long legal battle. Others never did. A similar tragedy unfolded in Niigata, on the northern coast of Honshu.

[2] Itai itai byou literally means “it hurts, it hurts disease.” Caused by ingestion of cadmium, this agonizing illness leads to loss of bone density and pain in the lower back and groin, among other symptoms. Men and women in the Jinzu river basin suffered the disease when cadmium-laden waste from Mitsui Group’s Kamioka lead and zinc mines washed down rivers, into paddy irrigation systems, and was absorbed by rice plants.

[3]The Tokugawa, or Edo, period (1603- 1868), was marked by political unity and relative cultural (though not necessarily economic or diplomatic) insularity, in contrast to the preceding period of internal war and external trade.

[4]In the late 1500s the powerful general Toyotomi Hideyoshi conquered one region after another, finally gaining control over all of Japan. Previously, the country had been divided among warring regional lords who paid little heed to the extremely weak central government.

[5]Copper extracted from the Ashio mines, in what is now Tochigi Prefecture, fed Japan’s technological, political, and military development as early as the 1600s. But smelting processes generated acid rain that denuded the surrounding watershed, and by the turn of the 20th century, a horrific cocktail of poisons increasingly leached from tailings into the nearby Watarase River. When the poisoned water flooded agricultural land downstream, over 250,000 acres of paddies and most of the life surrounding them were destroyed. “The disaster at Ashio is the first indication that Japan’s unbridled push to be a rich country with a strong military in the Meiji years would not be without costs: in this case, intense human pain,” writes Walker in Toxic Archipelago. The disaster also gave rise to what is regarded as Japan’s earliest organized citizen’s environmental activism, in the early 20th century. The mine closed in 1973.

[6] Eleven orca whales were crushed to death when they became caught between an ice-floe and the coast near Rausu, in eastern Hokkaido, in the winter of 2005. Villagers managed to save one member of the pod. Later, an underwater cameraman discovered the body of another female still embracing her calf. Tests revealed extremely elevated levels of PCBs and mercury in the dead whales, and Walker speculates that this caused deformities observed in the calves, which could have slowed down the pod, preventing it from escaping as the ice-floe rapidly approached the shore.

[7] W. Eugene Smith’s 1971 photograph of Ryoko Uemura bathing her daughter Tomoko, a victim of Minimata disease, brought global attention to the victims of this industrial disaster. In the photo, Ryoko looks lovingly at Tomoko’s face as she cradles the girl’s deformed and emaciated body in her lap.