Translated from the Japanese by Jeffrey S. Irish

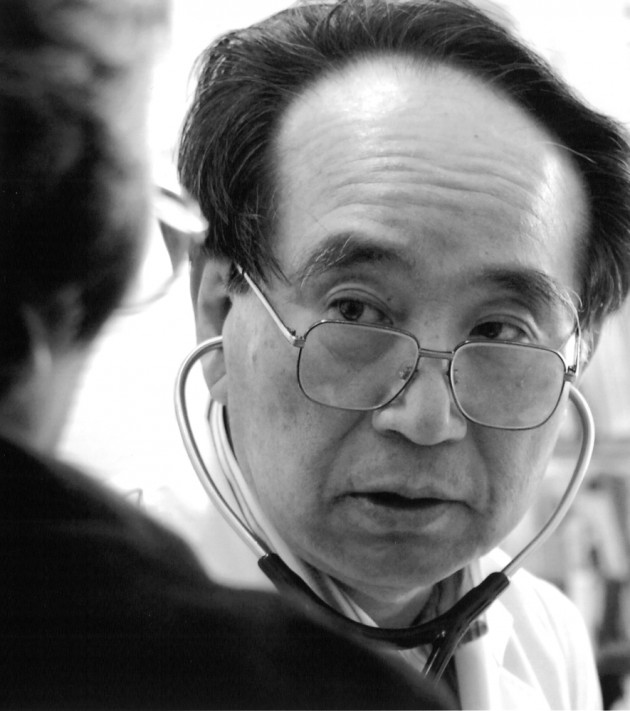

Kenjiro Setoue may be the most famous doctor in Japan, although few people actually know his name or would recognize a photograph of him. A manga cartoon, originally in Japanese and also translated into French, and an extremely popular television program were both made about him but under the pseudonym “Dr. Koto.”

His is a truly compelling story. Dr. Setoue (pronounced “Seh-to-way”) was a successful surgeon in a large urban hospital who had tired of the long hours and was planning to start his own private practice. He agreed, in the interim, to take a job at a clinic on a small rugged island off the west coast of Kyushu. That was back in 1978. Dr. Setoue only intended to stay for six months, but he has been there ever since. For many years the only surgeon on the Lower Koshiki Island, he was the last and only line of defense when there was a medical emergency. Dr. Setoue had to work hard to gain the trust of islanders who assumed that high quality health care was only available on the mainland. In time, not only did those who lived on the island turn to him for help, many who had left the island returned for an operation or to give birth to a child. In the meantime, the doctor developed a deep respect and admiration for his fellow islanders, as he learned from them about both life and death.

Japan has had a universal health insurance system in place since 1961, but for many years islands and remote rural communities either did not have doctors or suffered from a shortage of them. People were insured, but no services—or only limited services—were available to them. In an effort to solve this problem “direct care facilities” were established. At its peak there were more than 3000 such facilities nationwide, but with economic development, improvements in transportation, and easier access to remote areas, many clinics—having become obsolete —were closed, and the total number is now about 1000. Those that remain provide comprehensive health care to the local community, for they are at the frontier, responding to local residents’ medical, welfare and hygiene needs. Dr. Setoue has enabled the Teuchi Clinic to meet that challenge.

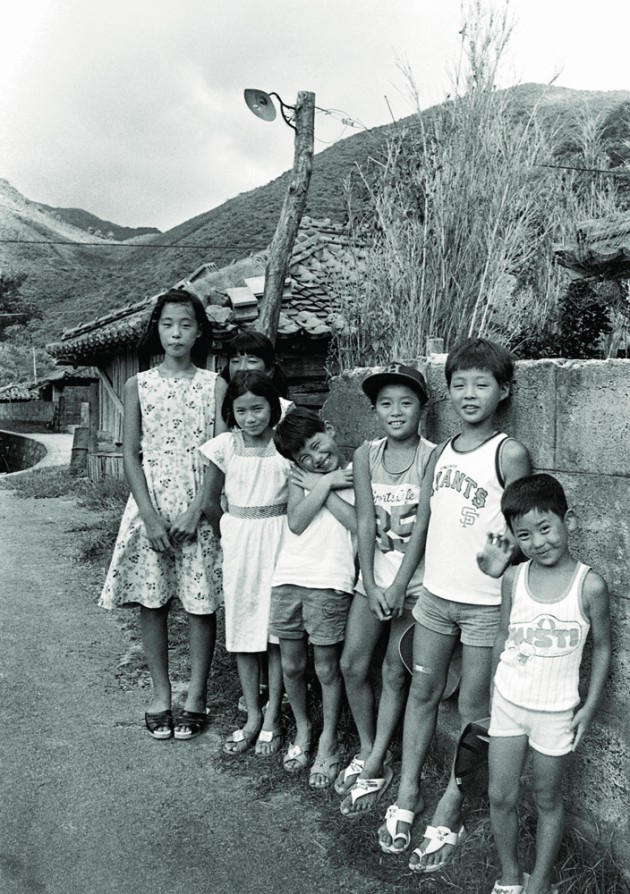

Japan is now one of the healthiest countries in the world and among the leaders in the provision of health care. At 86.4 years for women and 79.6 years for men, life expectancy is #1 in the world. The people of the Lower Koshiki Island have enjoyed longer lives in the postwar years as well, and with the departure of the island’s youth, who move to the cities, first for high school and then to find a job, the population has aged significantly. During Dr. Setoue’s 30 plus years on the island, the population has shrunk from 4000 to 2300, and the percentage of the population over the age of 65 has risen from 25% to 38%. In this sense the island is representative of nearly all of rural Japan where the population is shrinking and aging.

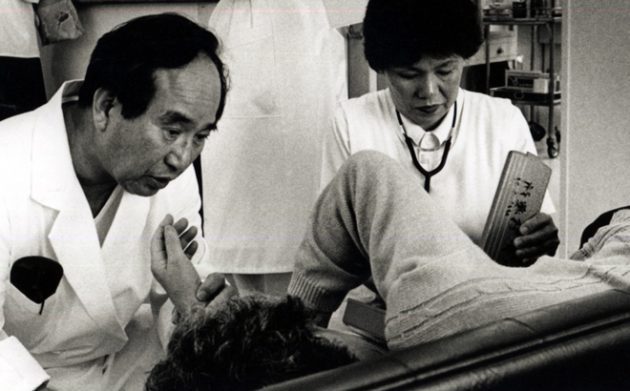

I met Dr. Setoue in 1990 and came to know him well in the three years that I lived on the island. I was working on a local fishing boat at the time, and I often visited elderly friends in the Teuchi Clinic and watched Dr. Setoue perform operations. I loved the way the doctor related to his patients, his habit of asking about their families and their day-to-day lives before delving into whatever ailed them.

When his wife was over on the mainland with his children, I often went over to his house for dinner and a good conversation. The entryway was inevitably piled with rice, sweet potatoes and bottles of the local shochu, gifts from the families of patients and from the patients themselves. I recall that Dr. Setoue was being courted to run a major hospital in Kagoshima City around that time. He did give the offer some thought, but when it came right down to it his heart was not in it and, besides, he never would have left the clinic without finding someone to replace him. And no one was interested in doing that.

When he told me of his journal I asked if I might read a few entries. I was taken with what I found there and kept going back for more. I have selected the stories translated here for what they tell us about the islanders, Japanese medicine in general and island medicine in particular, and the character of the doctor himself.

I feel honored to have this opportunity to share the life and character of this exceptional man and doctor with the English-reading world.

Jeffrey S. Irish

December 2012

May 2, 1978.

My wife and I boarded the ferry in Kushikino, a port town on the west coast of Kyushu. Six hours and several stops later we arrived at our destination, a fishing village on the southernmost tip of the Lower Koshiki Island, and the last stop on the line. When the ferry’s foghorn announced our arrival, the sun had already set behind the island, and dusk was slowly giving way to night.

Two local government officials and a small group of villagers had come to greet me and Mihoko when we walked down the gangplank. They took us to a small family-run inn not more than one hundred meters from the dock. We learned that we would stay there for a time until our residence could be put in order.

The local government held a simple welcome party for us that evening right there in the inn. By way of introducing the meal, the deputy mayor proclaimed that “the fish of the Koshiki Islands are the finest in all Japan. When one has tasted the sashimi here, he will no longer be able to eat raw fish in the city.” I thought the man prone to exaggeration until I tasted the fresh seafood laid out before us.

When the party was over and my wife and I were alone, the absolute quiet of this island fell upon us. No one else was staying in the inn, and the waves sounded very close at hand. Mihoko lay down to sleep but was unable to drift off. This quiet that penetrated so deeply seemed to arouse in her an uncertainty. Sounding discouraged, her eyes moist with tears, she asked “Why have we come here?”

The following morning, I reported for my first day of work at the Teuchi Clinic. A road and beach were all that separated the clinic from the ocean. I imagined the mix of sand and salt that would blast us during the typhoon season.

The steel entrance was rusted red, resembling a prison door. Inside I found a tatami-floored room full of patients waiting to be seen. Nearly all of them were elderly, and they smiled at me as if they had been waiting for some time. My first impression was “what a tranquil place this is.” In the examination room I found only a bed, a desk and a stethoscope, the single reminder that this was a place of medical practice. An oil stove in the corner for heating the clinic in the winter explained the sooty blackness of the walls.

There were two hospital rooms as well, each with a large wooden “bed” placed in the middle. While these beds were nothing more than raised framed tatami sections from a traditional Japanese room, they had an inexplicable warmth and stability about them. The adjacent X-ray and operating rooms were both so different from anything I had ever seen before as to be incomparable. The X-ray machine was old and could not produce a clear image. The operating table was rusted, a ready candidate for an antique sale. The astral lamp suspended above the operating table had four bulbs, one of which was burned out. The anesthetizer, generally an essential part of a surgery, was nowhere to be seen. Although referred to as “the operating room,” there was no evidence of its having been put to such use for a long time. One door into this room was broken, secured only be a strip of gauze, and a salty wind blew through the gaps in the window frame.

Back on the mainland I had been the head of surgery at a large national hospital and responsible at busy times for sixty patients at once. For most of the previous six years I had been in surgery day and night. During that time I had begun to plan a move into private practice. I had even bought land and commissioned an architect to draw up plans for my new office. But not long after I’d quit my hospital job with the intention of starting that new life, a man from the Lower Koshiki Island government office found me. The outlying islands were all actively searching for doctors then, and this island was no different. It just happened that their radar homed in on me. That was April 1978, and I had just turned 37 years old.

I agreed to meet with the mayor of the Lower Koshiki Island for coffee in the lobby of a hotel in downtown Kagoshima City. He was a likable man who wore the warmth of the island right on his face. When he told me of a patient with an intestinal obstruction who’d died while crossing the ocean on a chartered fishing boat, and of another with appendicitis who died for lack of timely attention, I was moved and alarmed.

When asked if I might consider a six-month term, I was torn between a natural desire to be of some help and an eagerness to start my own practice. I took the matter home to my wife, and we talked it over at length. Before making a decision, we asked many people for advice and finally it was my wife’s older sister who helped put an end to our confusion. Making use of Chinese directional astrology, she found that the island’s direction, due West, was propitious for both of us at that point in our lives. With this news, we made up our minds. Mihoko and I might be laughed at for paying attention to compass points, but there are times when, not knowing what to do, one must fall back on superstition.

While the island clinic that greeted me that first day was far more primitive than anything I had imagined, I could not run from this new arrangement. I had promised the mayor I would stay for six months. I was tormented by the fear that I would fall behind the rapid advance of medical science. I worried that what I had learned would grow rusty in a place so poorly equipped, and that I would lose in the rivalry with my classmates. These worries were magnified by my ambition, perhaps a drive common among young doctors. I resolved that to hone my skills and to spark a passion for my work, I would upgrade the facilities.

I would begin by arranging for the basic supplies necessary to medical care and, in particular, equipment for emergency cases. In this procurement and upgrade I enjoyed the full support of the mayor. As a doctor, however, I would soon discover that I had not yet gained the trust of the people. When I recommended surgery to a man with a liver abscess, the patient said “I would die before being operated on in a clinic here on this backward island” and fled across the water to Kagoshima. After all, the clinic was a primitive facility with only two nurses and a 37-year-old doctor.

I would have no choice but to wait and to rely on the power of positive results to build a relationship of trust here. For a time I sewed up external wounds and removed appendices, but soon enough the emergency cases started coming in: an external wound that perforated the intestine, an intestinal obstruction, peritonitis, an extrauterine pregnancy, and so on. These were all patients who had no choice but to stay, cases too dire to risk transportation to the mainland.

Our first emergency case involved a substantial loss of blood, and it occurred when I had only been on the island a little over a month. Katsuichi had been working in a stone cutting site when a 2-ton rock fell on him. His pelvis was shattered, and he suffered from deep cuts in his right leg. The right femur was fractured and protruding. The femoral artery was also severed, resulting in profuse hemorrhaging. The large intestine was ruptured as well.

Our first emergency case involved a substantial loss of blood, and it occurred when I had only been on the island a little over a month. Katsuichi had been working in a stone cutting site when a 2-ton rock fell on him. His pelvis was shattered, and he suffered from deep cuts in his right leg. The right femur was fractured and protruding. The femoral artery was also severed, resulting in profuse hemorrhaging. The large intestine was ruptured as well.

An immediate transfusion was our only hope of saving him, and we could not afford to wait for the arrival of blood from a mainland blood bank. We would have to take a collection of the patient’s blood type (AB) from among the villagers. The island public address system was a saving grace. “The Teuchi Clinic is in immediate need of a large volume of AB blood. Please help!”

Dozens of islanders rushed forward. Many did not know their own blood type, so one nurse tested for type while the other drew blood. Meanwhile, I worked to stop the bleeding and save the patient. The nurses being fully occupied, I asked Mr. Matsuda for assistance. An employee of the local government, Mr. Matsuda had been assigned to the clinic just one week before with the understanding that he would perform administrative work. Somehow he neither fainted nor ran from this grisly scene, but gave me a hand with the frantic work of clamping and stitching while Katsuichi, only under a local anesthetic, writhed, fully conscious and in unbearable pain. Although we did save Katsuichi that day, we were unable to save his leg.

To respond to such emergencies in the future, and toward performing major surgery, we would need a secure blood supply. A register of potential donors would be our next order of business.

PULLING THE PLUG

PULLING THE PLUG

“Can you keep my husband alive a little bit longer? Our second son has already left Tokyo, but I don’t think he’ll reach the island until nightfall. Can something be done, even if just ‘til then?”

Mrs. Nakano’s eyes were full of tears.

Two and a half years had passed since I operated on her husband for rectal cancer. The cancer had been quite advanced but the operation went well, and I was unable to find any evidence of its having spread elsewhere. Since his discharge from the clinic an artificial anus had liberated him from the persistent constipation that had preceded surgery. Perhaps more remarkably, he had given up drinking in his fight with alcoholism. A changed man, Mr. Nakano worked assiduously in a small country store that, like most stores here, sold virtually everything. This store was in his native Katanoura, a village of some 250 people in a windy ravine on the west side of the island.

Then, about three months ago, Mr. Nakano returned to the clinic complaining of dizziness. He was 60. Obstructed circulation to the brain is often the cause of such symptoms. But Mr. Nakano’s ataxia, or loss of coordination, was accompanied by headaches, potentially a sign of the spread of cancer. A follow-up exam revealed that it had, in fact, metastasized. Not only had the cancer returned, but it was spreading from one organ to another. This was the worst possible news, for nothing could be done. And when cancer spreads to the brain it causes pressure that results in dizziness, headaches and nausea. By the time these symptoms appear, the cancer has generally established a strong foothold.

Mr. Nakano was no exception. Within a month, he was no longer able to walk, and the cancer had apparently spread to his lungs and liver. Finally, he stopped breathing. Though respiratory standstill would have once meant immediate death, this is no longer the case. On an artificial respirator, the patient can be kept alive until his heart stops. Even in a small clinic on a remote island we have this technology.

Having said this, in a case like Mr. Nakano’s, there’s almost no point in applying such life sustaining care. For when the patient’s condition is so helpless—when the cancer has spread to the brain—the prospect of saving the patient is nil. However, in response to the family’s forceful demands, I did connect the respirator.

When Mr. Nakano’s family chose to admit him to the hospital, they had not given up the fight for his life. They wanted him to live, if even a day longer, and toward that end they were prepared to make use of any medical treatment.

When there is no possibility of a cure, and I can do nothing but treat the patient’s symptoms, the family will sometimes lose faith in me. This was particularly true when I first came to the island. Then, almost everyone was predisposed to think that effective medical treatment, even for a patient with terminal cancer, was available to them on the mainland. Convincing them otherwise has been no easy matter. It has taken time for the people to trust in my capability as a doctor and surgeon, and in me as a person.

When I operated on Mr. Nakano and when I subsequently admitted him to the hospital, his family trusted in my judgment and complied without hesitation. Even had they not asked, it goes without saying that I’d have done all I could for Mr. Nakano while awaiting his son’s arrival from Tokyo.

The artificial respirator moved rhythmically. The heart monitor drew an unvarying wave. Delivered from all pain, Mr. Nakano appeared to be sleeping quietly. Regrettably, he was already brain dead. His pupils were dilated. He did not respond to stimulus. That he had suffered only moments earlier was somehow difficult to remember or imagine. His 88-year-old-mother stood up from her chair beside his bed and wiped her son’s face with a small towel. She began to cry. Mr. Nakano’s wife and eldest son, not knowing what to do, stood solemnly by.

To this somber and increasingly oppressive atmosphere the Nakano’s second son returned. After flying from Tokyo to Kagoshima, he had rushed by taxi to the port town of Kushikino and chartered a fishing boat to bring him across the water.

“Father!” he called out, running into the room. But finding his father unable to respond in any way, all other words failed him. At such times, a doctor can only get in the way, so after briefing him on his father’s condition, I left the room.

One night passed. Mr. Nakano’s blood pressure was quite low, hovering around 80, but his appearance was unchanged. The family was silent, as if all thought had been suspended. There in the room beside them, the artificial respirator and electrocardiogram continued to quietly mark time.

On the morning of the third day, the family showed signs of fatigue.

“Are you sure his eyes won’t open?” Mr. Nakano’s wife asked me for the second time. Though she was able to understand, in words, that her husband was brain dead, she was unable to give up hope when looking upon a man who truly did appear on the verge of awakening.

“There’s no hope.” The patient’s mother dropped these solitary words as if to hear them fall.

The morning of the fourth day arrived. Respirator and cardiogram continued, as before, to notch the time. Mr. Nakano’s expression had not changed in the slightest. But the family was showing signs of resignation. They had begun to pick up around the hospital room.

“We would like to take him home now.” This suggestion was made by Mr. Nakano’s wife, and entirely out of the blue. “My husband’s mother has suggested that the end might be best at home.”

I was surprised. I hadn’t anticipated this request. Certainly, I’d had many cases of sending a patient home immediately prior to their death. But this time the patient was attached to, and being kept alive by, an electrically powered respirator. There was no possibility of his going home, at least not alive. Pulling the plug would mean an immediate end; his breathing, unaided, would stop, and his heart soon after. Though I understood the family’s feelings, I doubted they had fully comprehended the meaning of disconnecting the respirator.

“This has gone on long enough. I’ve talked it over with my sons. All that remains is to fulfill their grandmother’s wishes.” Mr. Nakano’s wife spoke, in tears. Apparently the family was coming to terms with this death. The aged grandmother and Mr. Nakano’s two sons looked down at the floor. It was a little after 10:00 in the morning.

I would have to respond, but this was not as simple as saying “Yes, I understand” and disconnecting the respirator. I’d been caught off guard. I too would need time to prepare. I proposed that we turn off the respirator that evening at 5:00 and the family agreed.

On my rounds just before noon, I found Mr. Nakano unchanged and the family silent, though without the same tragic feeling they’d had before. Thereafter, I visited the room every hour. The thought of pulling the plug weighed heavily on me. I even found myself wishing that Mr. Nakano’s heart would stop of its own accord before 5:00. But nothing happened and the hours passed slowly. With each visit, the family’s faces grew more overcast.

“Doctor, it was 5:00 wasn’t it?”, Mr. Nakano’s wife asked in a weak, depressed voice. I nodded, though still unable to bring myself to fully accept the decision. And 5:00 drew steadily closer. At five minutes before the hour, I entered the room. I was feeling perhaps the way an executioner feels. Mr. Nakano’s wife and two sons began to cry aloud. The grandmother quietly closed her eyes. I too closed mine. Why do we have to suffer so, bound hand and foot by a situation we ourselves have created?

Once, previously, I had faced a similar situation. Mr. Haruta, an 82-year-old suffering from internal bleeding accompanied by confusion, headaches and impaired consciousness, had fallen. He was in much the same condition as Mr. Nakano. At that time Mr. Haruta’s eldest son and the son’s wife returned to the island from their home in Osaka. Shortly after entering the patient’s room, the wife, herself a nurse in a large urban hospital, turned to me and said:

“Doctor, ‘natural cause’ please.”

At first I didn’t understand what she meant. Then I realized she wanted the artificial respirator removed. If her father-in-law was unable to breathe on his own power, there was no point in prolonging his life with a respirator. The matter was cut and dry.

“As this is an important decision, please discuss it once more with the entire family.”

“We’ve already discussed it many times.”

“What if you were to talk it over again? Besides, you’ve just arrived on the island. This condition cannot continue for many days. Perhaps you could attend to him, give him some final care?”

I made these suggestions, but my words went unheard. As if pulled along by his wife, Mr. Haruta’s son then said:

“Please, we all have jobs to get back to.”

That was a first for the Teuchi Clinic. When the respirator was disconnected, Mr. Haruta’s heart stopped in less than three minutes. Later, his island relatives and other villagers remarked that they’d never encountered anyone quite like the eldest son’s wife. We all were left with a bad feeling.

This time circumstances were different. All had taken ample time to nurse Mr. Nakano and the grandmother’s request was understandable. Yet, there was something unbearable about the thought of pulling the plug on the respirator.

“Shall we leave him be? Perhaps watch things a little longer?”

I asked this when it had turned 5:00, and it had become clear to me that I did not have the will power to turn off the machine.

“Can we? Can we watch over him a bit longer?”

Their faces suddenly brightened. Who could possibly object? After all, it had been their idea in the first place.

“That will be fine.”

The grandmother, relieved, spoke softly. That same night, and of its own accord, Mr. Nakano’s heart stopped beating.