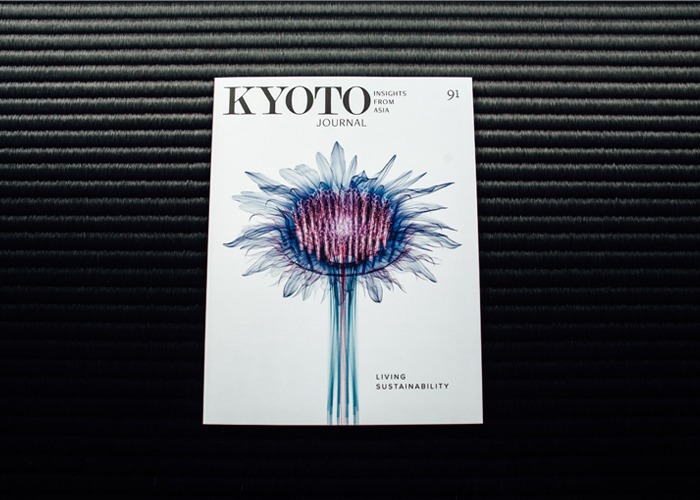

Local tatami artisan Mitsuru Yokoyama’s distinctive work has become highly recognisable among Kyotoites, and increasingly overseas. If you follow us on social media, you may have noticed in recent weeks since the launch of latest issue, KJ91: Living Sustainability, his tatami gracing the background of magazine spreads shot by our Minechika Endo. Mitsuru’s endeavour to take the versatility of the humble mat to new heights is just as impressive as his technical mastery of the craft and commitment to handmade. New KJ volunteer Leo Gopfert corresponded with Mitsuru over e-mail to find out more.

When did you decide to become a tatami craftsman, and why?

It is a long story now, basically I was living in Australia with my now wife and felt a need, I guess really a desire, to transmit my culture. I wanted to share something about Japan with the world. I heard so many stereotypes about Japanese culture living in the USA, Australia and Europe and I felt that if people could understand something deeper it would be nice, for them and for me! I had been away, and in and out of Japan for so long, looking back I guess I wanted to reconnect too. I wanted something for myself that no one could take away from me, that manifested as a traditional skill.

The style of Tatami has been so consistent for hundreds of years. What prompted you to change the traditional design?

It isn’t really changing it, it is just adapting. That is critical today. So many traditional artisans all over the world can not survive with cheap imitations and consumers not knowing the difference in quality. People don’t have so much money anymore so I can understand they look for cheaper options but you can’t compare the quality or the longevity. What I make, and all Japanese craftsman make ages with you. This is an investment in yourself, your life. I really believe that something you have for a long time makes memories with you, fits you. I guess it’s part my culture and partly because I traveled a lot, with no money, so the few possessions I have that actually matter could probably fit in my pocket. That’s not intentional, it just happened like that. Now I have a family so this has changed, but I hope we can always keep this spirit!

What pigmentation do you use to make your tatami so jet black, and has your crafting process changed over the years?

My process hasn’t changed for traditional tatami. What has changed is the approach. I do a lot of collaborative work with my wife Lauren, with designers, architects and other craftspeople. The ideas don’t always work out but its good to adapt and try things while being sensitive to the material and craft.

For the black it’s been though many realizations. What you usually see is commercial dying, but the unique artisan work I do with black is different. It is hand dyed, handwoven and hand-sewn onto a natural base. This is really beautiful! I use a Ryukyu (Okinawan) weave, its more rustic.

How did your involvement with the Kyotographie International Photography Festival begin?

My wife was a core member of the organization from the first edition so I know the festival really well. The founders have always been supportive of my work and encouraged me, they understand how important traditional crafts are. Because the festival is really sensitive to architecture, craftsmanship, and the harmony of space, doing something with the tatami had come up a few times but it wasn’t until this edition (2018) that a large-scale installation really made sense. The Yukio Nakagawa exhibition, Flowers at Their Fate was right exhibition in the right location. Curated by Atsunobu Katagiri and including his flower installations, it was held inside such an impressive venue, Kenniji’s Ryosoku-in temple in Gion. In 2017, I also worked with Yan Kallen and other Kyoto artisans to realize Yan’s camera obscura installation in his exhibition as part of Kyotographie.

I am always proud to be a part of such a progressive festival and i really love working with creative people.

Your work is being used in places such as the Kyotographie Festival and artist studios in LA. How has the role of tatami changed over your career/ lifetime?

Tatami has changed mainly due to demand. Japanese people opt out for a more western style space, others use cheap imitations. There are exciting changes too, like alternate architecture and interior styles coming from abroad. Tastes change but the core product and my craft is exactly the same. This I am very proud of. It shows that it is a resolved product in material and design. People try to change it all the time (me included) but it generally always comes back to its original form, or a slight variation on that.

Photos on Instagram of your tatami reminded of the controversial ‘Black Paintings’ by Ad Reinhardt. Do you think of your work as art, furniture or both?

Well, I am really flattered it evoked Reinhardt for you!

In terms of art or furniture, tatami should be regarded a little differently I think, it is hard to categorize, it is a living piece, living with you, it creates an atmosphere. That’s the beautiful thing about tatami, it is so functional. It is hardy and clean while powerfully elegant. You can experience your entire life on it. We (Japanese) treat it with respect but tatami is daily, sure there are really special places but for the most part there isn’t a ‘special’ room you only use on certain occasions. This is because it is central to lifestyle. Essential in the functioning of a home; a space to sleep, for communication, dining, meditation, worship, entertainment, and so on. Because of this ability to gather experiences I think tatami is really more of a ‘space’ than an ‘object’.

You can contact Mitsuru and see more of his work at www.yokoyamatatami.com