[M]inako Itosaka’s grandmother told them to leave her. They had only minutes before their home would be filled with sea water, and her legs were bad. She would only slow them down. Minako tells a room filled with friends that she is proud of her grandmother’s strength. Many Japanese elderly did the same thing that afternoon in mid-March; they sacrificed their lives, urging loved ones to save the grandchildren and live good lives. It was a day that changed Japan.

Minako, who lives with her Chinese husband and children, sat on a green cushion on the floor next to a table. Sunlight shone into the room and the women congregated there to bask in it like cats soaking up its warmth. With a serene smile, and only a hint of grief in her eyes, Minako told them she knew her grandmother was free now and would be happy to be with her grandfather who died many years earlier. Though Minako was not in Japan that day, she heard the story from her uncle who had to leave his mother behind to save his wife and himself.

The friends surrounding her included a Persian-American raised in Louisiana, an Israeli of Italian origins, a Cantonese born in South Africa but raised in Canada, two Americans and another Japanese lady. They had gathered to honor and remember the victims and survivors of the earthquake and tsunami that struck the northeastern coast of Japan at 2:46 PM on March 11th, 2011. They spoke in their common language, Mandarin.

The gathering took place in a beach village north of Dalian, China, one thousand miles directly west of the epicenter of the earthquake. Dalian has a long and mixed history with Japan. It is the site of the initial invasion in 1931; the anniversary of the invasion is still observed every September when sirens are sounded at the same time they were originally heard eighty years ago. In 2012, tensions across China were intensified during the days leading up to the anniversary because of the territorial dispute over uninhabited islets in the East China Sea. Cities across the country raged in protest against Japanese companies and individuals based in China. Yet no anti-Japanese protests were reported in Dalian. The region has strong economic ties to Japan. Much of the initial foreign investment in Dalian after the re-opening of the Chinese economy came from Japan.

Following the tsunami, the attention of the world was riveted by the pictures and stories of the destruction left in its wake, and also by the increasing danger caused by the damaged Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant where workers have been scrambling to prevent a meltdown. In Dalian, there were mixed reactions to these events. Those whose minds had been calloused by the bitter history of conflict between China and Japan cheered at their enemy’s misfortune. Those who remembered the 2008 earthquake in Sichuan Province were filled with empathy. And then there were the profiteers.

Salt prices rose in one afternoon from 1.5 RMB to 15 RMB (over $2) for a small bag in one neighborhood; similar price hikes were seen around the country. Why salt? A rumor was spread across the country via text messages that the iodine in salt can prevent radiation poisoning. To get the proper dosage of iodine, one would have to eat 3 kg of salt. Rumors were also fueled by fears that salt produced from seawater would be contaminated with radiation. Uninformed shoppers around China stockpiled the stuff. In California, shoppers stockpiled iodine tablets for fear of a nuclear cloud floating across the Pacific. In Japan, people calmly queued in order to buy bottled water, and only bought as much as they needed.

The debate continues around the world about whether nuclear power should be used because of the risk of a meltdown and the dangers posed by spent fuel rod transportation and storage. People in Dalian have reason to worry. Wafangdian, a large town less than an hour north, is home to the Hongyanhe Nuclear Power Station. I asked my students about their opinions. Many have a fatalistic perspective. One sophomore said, “If I were going to worry about something that could kill me, I’d worry about the chemicals surrounding us. But I don’t, because everybody dies. So we should live life to its fullest.” He was referring to the chemical and petroleum processing plants that surround the Dalian Bay. In the summer of 2010, during a transfer of oil from a Liberian tanker to a storage tank, a pipeline exploded spilling an estimated 1500 tons of oil into Dalian Bay devastating the coastline. The explosion could have ignited nearby chemical storage tanks resulting in the deaths of hundreds of thousands in the city.

[pullquote]The Chernobyl accident has also been linked by historians to the fall of the Soviet Union after protests about nuclear power sprang up in the previously docile population[/pullquote]

But living with the threat of death over one’s head doesn’t stop one from living. The people of Chernobyl can attest to that. Michael Forster Rothbarts is a photographer and Fulbright scholar who created a photographic exhibit called “Inside Chernobyl” which debuted in Kiev in 2009 and has been displayed around the globe. The exhibit shows the lives of those who live in Chernobyl today over two decades after the meltdown that devastated the region and spread nuclear contamination around the globe. Forster Rothbarts wanted to explore the effects of the disaster a generation later. He says, “I am fascinated by the human consequences of environmental problems. Journalists cover environmental disasters as breaking news, and then they get filed away, but the repercussions continue.”

The exhibit was first displayed on the interactive media sharing service called VoiceThread, which allows web viewers to comment on what they see and hear. The recent events in Japan have spiked interest in the site. The exhibit has haunting photos of a library, school room, and a vehicle in the village of Priyat, all abandoned and covered with dust. They are juxtaposed alongside vivid pictures of people living their lives: a church service, a grandfather with his grandson’s arms draped over his shoulder, a family visiting the local cemetery where those who served in the Chernobyl clean up are buried, and an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting. Forster Rothbarts comments that the largest public health problems after the accident are not radiation related, but rather are the increase in mental health problems, including depression and alcoholism. But the accident has also been linked by historians to the fall of the Soviet Union after protests about nuclear power sprang up in the previously docile population. Life goes on.

What effect will the devastation in northeastern Japan have on that country and on the world? Suresh Kumar, a professor from India, wrote a blog post in which he describes the qualities displayed by the Japanese during this crisis as “10 Things to Learn from Japan”. The list includes things like “dignity”, “sacrifice”, “calm” and “training”. He describes a Japanese population that responded to their plight with the utmost humanity. There was no looting or stockpiling, no images of weeping and wailing spread through the media, no sensationalist reporting. The people queued calmly, businesses reduced prices, and everyone knew just what to do when the emergency hit, both young and old. Mr. Kumar writes from personal experience of living in Japan as well as from research he has done. He says that Japanese culture instills a sense of shame rather than guilt, and is a tightly-knit reality. Even in very large cities, people know their neighbors, so everyone is motivated towards “good behavior”.

Obviously, culture is not enough of an explanation. My Chinese students can recite the atrocities the Japanese committed in nearby Lushun when they invaded during World War II, or in the Massacre of Nanking. Discussions we have held in my English conversation course have revolved around the bitter feelings that still exist between the two countries, always with references to “what they did to us.”

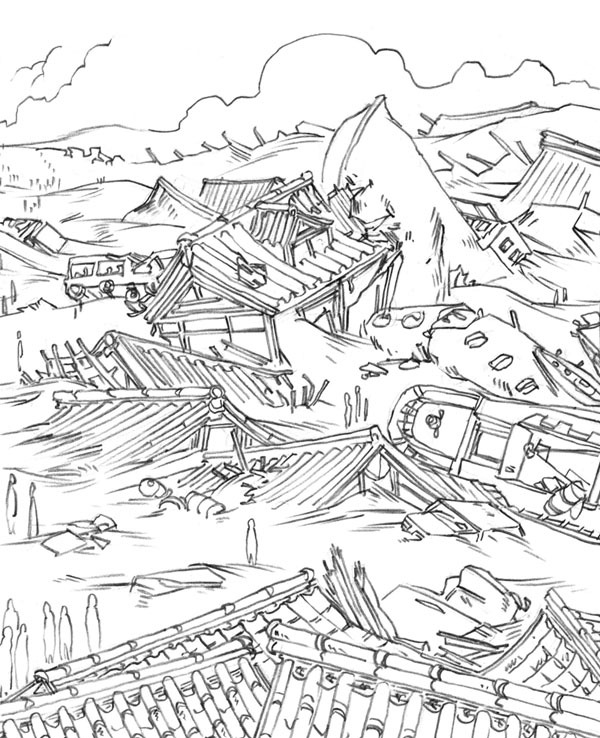

A week after the disaster, however, I observed a most powerful transformation. One student, Jackie, a well-read and quiet young man who has defended the Chinese mistrust of the Japanese in the past, spoke about the 50 workers at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant who stayed behind to help mitigate the effects of the ongoing emergency. “Seventy percent of them,” he said to my class, “will be dead within several weeks. This is according to American news media,” he clarifies, to add credibility to the statement. Although much of this turned out to be media hype, and the circumstances surrounding those fifty men are still clouded in controversy, the effect of their act on this young man was profound. He spoke about the example of restraint that he saw in the Japanese. He spoke of the devastation. “I thought it wasn’t a big deal at first. Japan has earthquakes all the time. Then I saw the satellite pictures.” These web-based images allow the viewer to see before and after the tsunami, and to zoom in from a very high level to several dozen meters above the scene. What was once a green and flourishing community is now an otherworldly pink-brown swath of…nothing.

“Now I write in my blog to encourage my friends and families to let go of the past,” Jackie says, “We are all brothers. We are all brothers.”

That afternoon in late March, when Minako Itosaka told her grandmother’s story to her friends, she said something has changed in Japan. Japanese are very self-reliant, very convinced of their ability to do things on their own. But after the tsunami, she said, they see something greater than themselves. Despite all their technology, despite their development, towns were washed away and a nuclear power plant hangs on the brink of more disaster. There is a heightened awareness of spiritual reality in Japan, Minako said, an increased interest in prayer and religion. We saw that in China in 2008 after the Sichuan earthquake. Then, even the government called on people to pray for the victims and survivors. And so we did, as we do now for Japan, as those in Chernobyl still pray. Life goes on. The people whose lives were lost, including Minako’s grandmother, would want that for us.

Amalia Giebitz lives for part of every year in Dalian, where she works as an English teacher at a local college. She is also a contributing editor and writer for one of the local English magazines, Focus on Dalian. The rest of the year, she lives and writes in central New Mexico.

Illustration by Alexander Draude