Mizuho Toyoshima and Hana Murrell

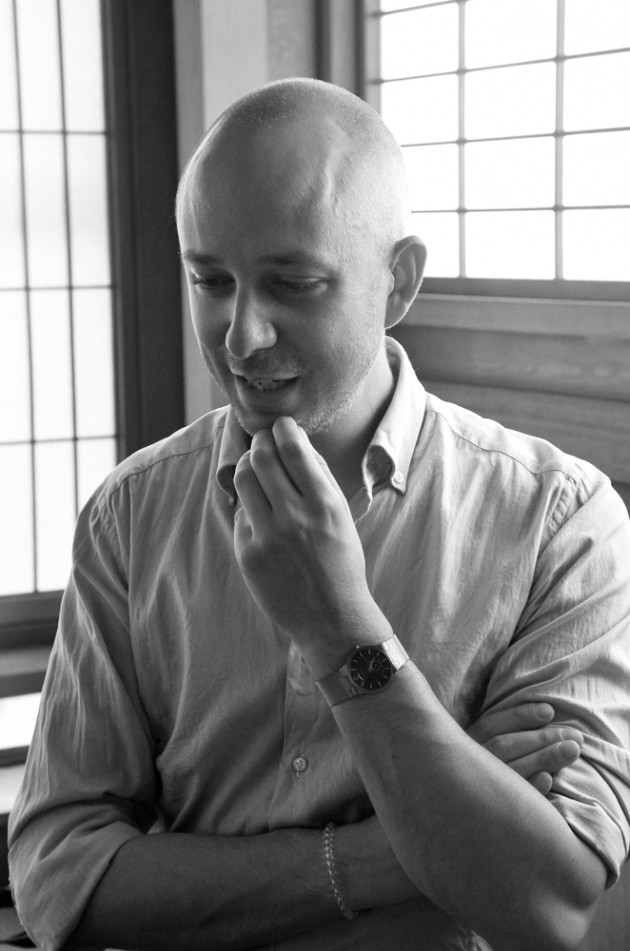

Diego Pellecchia, from Brescia, Italy, has practiced Noh since 2006. He is currently a visiting researcher at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto and an associate researcher at the Italian School of Asian Studies. He studies Noh theatre with Kongo School actor Udaka Michishige. On June 29th, he will make his debut as a main actor (shite) in a performance of Kiyotsune at the Kongo Noh theater, as one of the very few foreigners in history to perform an entire Noh play. KJ contributing editor Toyoshima Mizuho and intern Hana Murrell talked with him recently in Kyoto.

KJ: Why did you take an interest in Noh theatre?

DP: I was studying Shakespeare but as literature, not as theatre. In fact, I wasn’t that interested in theatre back then. However, I’ve always liked cinema and I thought I would like to do my thesis on cinema, Shakespeare, and possibly something ‘exotic,’ a bit different. I found a Kurosawa Akira film based on Macbeth called Kumonosu-jō — literally “The Castle of Spiderwebs” — but its English title is Throne of Blood. Kurosawa used many elements from Noh in the film — masks, music, timing. I liked it very much and wanted to learn more. I looked things up on the internet, and found Monique Arnaud, a licensed instructor of Noh living in Milan, so I went to interview her. She was doing a Noh demonstration and I was meant to talk to her beforehand. But I actually ended up working for the demonstration, not talking. I understood later that’s how traditional arts in Japan are. They immediately confront you with something to do. I wanted to do my interview, so I went to meet her again. I went to her house and she encouraged me to start practising. Sooner than I could realize, I already fell in love with it. I spent a year practicing shimai, dance excerpts of a longer play. It’s like an aria in opera. In shimai, only one person dances without a mask or costume, at the accompaniment of a chorus. I didn’t know Noh; I’d never seen the real thing. I hadn’t even seen videos. I studied with Monique every Sunday for a year.

As you might imagine, Milan is a grey, concrete city. It’s not poetic at all. But in Monique’s apartment, we would do shimai from Kiyotsune, Yuya (which is partly set in Kiyomizu-dera), and Tsurukame, which is set in China. These are basic dances practitioners study from the beginning and we’d spend the day practicing. In the summer of 2007, Monique did a full Noh, Aoi no Ue, and asked if I would like to be in the chorus. I spent six months preparing and then came to Japan for the first time. Two days after I arrived, I saw my first Noh play. I also met my teacher, Udaka-sensei.

Did you already have an interest in Japan or did this develop alongside your interest in Noh?

I suppose I was interested in the way that everyone probably is. I hadn’t been studying the language. I couldn’t even read furigana. Of course I can now, but back then, I would play a tape of Udaka-sensei reciting. By the time I met him, I already knew his voice very well because I’d been listening to it every day for a year and a half. Because I didn’t understand a word, I could let my mind fly along and imagine. I knew the story and I knew the translation, so I understood what I was saying, more or less. I studied with him for two months and then we had a recital. Monique did Aoi no Ue and I did my shimai. In the end, the chorus for Aoi no Ue became a female chorus, so I couldn’t be part of it. This is how it works. You always have to be ready for change. Everything in Noh seems so fixed and crystallized, but that is only an impression.

I liked it so much when I was here, and I wondered how I could continue. I didn’t know Japanese, I didn’t have a degree in Japanese studies, and I was twenty-seven. So I decided to apply for a Ph.D and I was lucky enough to get a scholarship from Royal Holloway, University of London. My plan was to study the reception of Noh in Europe. Now I realize that I was looking for the reason why I was studying Noh. I was also studying Japanese part-time in the evenings, which was crucial for my advancement in the world of Noh. I got travel grants to come back to Japan for my research and so I continued my practice with Udaka-sensei.

You said that you used to be a music producer. The environment of your former profession is so different to what you do now.

I was working with pop music, in recording studios and with some important acts. Nowadays, in pop music, producers work with computers. You can basically do anything you want in the studio: from electronic to heavy metal, from reggae to jazz. You are lost in a myriad of possibilities. Everything sounds interesting and everything is possible. What Noh offered was the opposite: something apparently very defined and regulated.

In a studio, you’re relaxed. You’re there to work, but you smoke cigarettes, eat pizza, and play. At some moment you get inspired and then create something. At some point, you have a deadline and you have to hand the work in. It could have been done in a thousand other ways. It’s very random and very creative. This randomness didn’t appeal to me anymore when I discovered Noh. When you’re too free, it’s not interesting. Imagine football without the rules. What do you do?

At the beginning of Noh training, you rely entirely on your teacher. He or she would tell you what to do and you have to do it. Period. Unlike contemporary theatre there’s no intellectualization or psychoanalysis of the character. You take two steps, you go two steps back. You lift your right hand and then your left. You open your arms and then go back to the basic position. You just have to do it very well. I like the idea of polishing one simple action and taking it to perfection. It’s probably closer to what people like about martial arts rather than about artistic endeavors like painting. I think noh is very close to martial arts. You repeat a movement until it’s good. That’s all you have to do in the beginning. The only way I could understand noh in the beginning was through practice. This appealed to me. If I didn’t practice it didn’t exist. You have to take yourself away and just receive. You’re not involved. At least, this is what I thought in the beginning. My understanding has changed.

What do you think now?

You can’t do away with yourself. This is a superficial understanding of Japanese traditional arts and practices. Let’s say that Noh practice does not encourage intellectualization or verbalization of the many questions one would have. You need to put in standby your ‘self’ in order to allow the teaching to come in. You step back a little. My teacher uses the Buddhist metaphor of the cup. You have to empty the cup. Otherwise, you can’t fill it.

Let’s look more closely at what is actually happening on the stage. How important is the music to the rehearsal?

Noh is like ballet, so music and movement live together. Actors need to rely on musicians for some moments. In other moments, the musicians will follow you as the conductor. Musicians and actors exist in dialogue. Ma, or empty space, is created by good communication between hayashi musicians and utai chant.

The masks are quite amazing. To look at them and to think they were done by hand.

My teachers are self-taught, so it’s possible that you could make a mask yourself, though it takes a long time!

Are there any barriers and hardships in Noh?

Noh certainly is a very demanding practice. It’s interesting because it’s so difficult and there are so many barriers. The rules are really, really strict. Because of this, you have many chances to test yourself. I’m thankful for this and was actually seeking it. Without rules, I wouldn’t have enjoyed it.

When you’re the shite, how much freedom or latitude do you have in adapting the space? Is that up to you or is it really written in?

It’s difficult to generalize because all actors have their own way of doing things, but it depends on the stage you are at in your study. In my case, I am an amateur, so I have no freedom at all. My teacher started adapting what he had learnt to his style when he was fifty years old. In my case, my efforts go into doing what I’ve learned from my teacher well. I don’t think, ‘how shall I do this’? Instead, I think about how I can do what I think I’ve understood from my teacher. It is also important to adapt the body to your own physicality. My arms are longer than those of the average Japanese man? This changes the way I move on stage or the way I wear the costume.

Would you say that each individual has their own difficulties, regardless of their background?

Absolutely. There’s no specific difficulty. I think that some teachers might bring some people together with their psychological, physical or cultural features, but no. Although you would expect Japanese people to be more familiar with the traditional okeiko environment, some people give up because they can’t stand the strictness. Again, there are so many ways of teaching Noh. My experience is my teacher’s way of teaching. I have observed other ways of teaching, but I have just one teacher. That’s it. My teacher’s son is much more kind and accommodating. There are many teachers and many processes.

Is there a separation between the professional and the amateur actors?

In Noh, amateurs belong to a ‘kai’, or group, led by a professional, who is the teacher, who organises training and performances. This way amateurs and professionals co-exist in the same social and artistic environment.

Do you have difficulties with the Japanese way of performing this art?

I think there are many difficulties for foreigners on the stage. The language, body shape, other people in the Noh world. My teacher clearly enjoys teaching foreigners, and he accepts them in the same way that he accepts his Japanese students, but this might not apply to all teachers. Also, not all teachers teach amateurs the way Udaka-sensei does. Many teachers consider amateurs as hobbyists. Udaka-sensei, instead, puts exactly the same effort into training amateurs as he does with professionals, so the relationship becomes very close. He gets angry, he stresses out. This is very good and it’s why we are able to do full Noh plays. He pushes us to grow up as much as we can.

Does he make any distinction between foreigners and Japanese?

No. The only distinction is that, in the case of foreigners who can’t speak Japanese, he speaks English and he’s very happy to do this. I think he likes teaching foreigners because he learns a lot from it too.

When students have problems understanding because of linguistic or cultural gaps, I think Udaka-sensei enjoys it because it then becomes his own okeiko. He has to explain things in a way that he hasn’t explained them before. He loves challenges. He’s a very self-made man.

Why do you think that anybody can perform Noh?

I can’t think of a reason why not. You can learn many things through practicing. I hope that more and more people from other areas of existence will come to our group. For example, other Asians or Africans. I also hope people with disabilities will try it. I’ve seen some disabled Japanese people perform, mostly very elderly people and both professionals and amateurs with difficult issues. There are many studies and efforts to study theatre and disability, especially in England and North America, but I haven’t seen much with regards to Noh.

In your upcoming performance of Kiyotsune, you’re providing explanations in English, French, Italian and German. It seems like you want to open Noh up to foreigners. There’s also an International Institute of Noh in Milan, so there’s this idea of trying to reach out to a Western audience. What values does Noh have that you think would appeal to this audience?

What I’m hoping to do is to transmit the ethics of Noh. Respect for the space and discipline, work ethics, orderliness, cleanliness. The problem with teaching these aspects, at least in Italy, is that as soon as you start talking about discipline, rigor and respect, you sound like a nationalist. Unfortunately, tradition runs with facism in Italy now.

There’s a tremendous difference between them though.

Of course, but unfortunately, this is twentieth century history. Noh was actually used in the past, as were all arts, as a means to transmit certain extreme ideologies during the imperial period.

Was there anything in your upbringing or in Italy that has helped you with Noh?

Knowing nothing about Noh helped me learn about Noh. Complete ignorance of the language also helped a lot.

If Noh comes up for some reason when I talk to some Japanese, they might say their great-grandfather used to practice it. The way Noh is presented on TV and commercial media here in Japan really is that way. They don’t show very young or cool actors, even though there are plenty of them. They have this image of Noh being a very boring, aesthetic art. I didn’t have any of these preconceptions. For me, Noh was really cool.

Special thanks to Annabella Massey.