[M]editation practice never works the way you think it will. You think it’s working in one part of your mind only to realize it’s actually rearranging a wholly different part. Fukushima is the same way. I thought I’d go to Japan to bring blankets to displaced families, meet scientists and young people re-imagining what’s possible. I’d come home inspired by new ideas about technology and social change. I wanted Japan’s response to the nuclear meltdown in Fukushima to be a crystal ball for how we’ll change here in North America. The Japan I thought I was visiting turned me inside out and without knowing it at the time, the pilgrimage rearranged the way I thought I could help.

In Montreal, attending the final day of the Zen poetry festival, I listen to Jane Hirschfield, Kaz Tanahashi and Robert Bringhurst read poems in the tradition of Japanese monks who wrote about pristine mountains and rivers. I think about the long flatbed train east of Regina I saw on a winter day last year. It was loaded with uranium in dark steel cases destined for Canadian-built reactors in Japan and India. Nobody at the festival speaks of the devastation though we all know an earthquake just tore a hole through Japan.

Checking my email once I board the plane in Montreal, I find a letter from the Zen teacher and poet Peter Levitt. We were planning to visit Kyoto together the following March during cherry blossom season to lead a walking pilgrimage through the old Zen temples and gardens. He writes:

“To really allow in what is happening – the scope of it for the Japanese people, their future, much less their present losses – is a cause of incalculable sorrow. I don’t mind being in this with them, but I sure mind them being in it at all. The Japanese people were sacrificed so that all may see the horror of nuclear war, and now they have been sacrificed again, due to yet another form of our ignorance, so that all may see the horrific actuality of nuclear peace, as opposed to some drawing-board dream of nuclear perfection. It is a horrible sacrifice to have to make and I grieve for them, one of the many who do.”

He goes on to say that he has decided not to go to Japan, that at this time it would feel odd to make a pilgrimage to visit cherry blossoms, temples, and the homes of great poets. I understand where Peter is coming from, but I disagree. It’s not just the infrastructure that lies in ruins; it’s an entire world, a belief in endless progress and cheap energy. Emerging from the wreckage, what the Japanese are going to need to rebuild is a set of values, ethics, and new ideas for how to live differently in modern industrialized cities. Will this be possible? I am not sure that I even understand what’s happening right now in Fukushima. For me, this is a big part of why I feel I need to go ahead with the trip.

[I]t was only three days ago a 9.8 magnitude earthquake and ensuing tsunami tore a gap in the earth 400 km long and 160 km wide, and today the threat of a nuclear meltdown at Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant has the world’s attention. Cities burn from Chiba, east of Tokyo, to the northern Japanese islands of Hokkaido, 500 km north of the quake’s epicenter. Near Fukushima anything by the water has been ripped from its foundations and pulled out to sea. Anything standing is broken or burning. Everything is water and fire.

As the fear of full-scale meltdown grows due to a hydrogen explosion blowing the roof off the damaged nuclear plant causing the Tokyo Electric Power Company to make the decision to release radioactive steam into the skies to relieve the increasing pressure within the reactor, the world listens helplessly to news of spent fuel rods heating towards the critical 1200 degree Celsius mark. It’s the temperature at which their zirconium casings break down and the fingernail-sized uranium pellets lose their shape. When the uranium pellets melt it’s crucial they don’t mix with the outside air, or a full meltdown ensues. Cold water is essential for keeping those pellets cool.

I wash my face in cold water while the news carries on through my room. Even as images, the waves are so tall and frightening it looks like for a moment the whole world is tilting too far. People have video cameras pointed at the waves that come rushing towards them like a train.

The waves crush the shore and start flipping cars like pieces of Lego. In a matter of seconds people realize the waves are coming for them. And the ocean is on fire. It’s strangely biblical. It’s death and it’s terrifying. Waves at 400 miles an hour, the radio says.

These are images I’ve put together myself. The mainstream media reports are confusing and troublesome to me because of the gaps that are being left. “It’s a terrible choice,” says one engineer as the decision is made to vent radioactive gas. “If you vent this material into the atmosphere it will be gas with a very high radioactive content. If you do not vent and you allow the radiation and therefore the pressure to build up in the vessel, you raise the possibility of this vessel exploding.”

Choppers are dumping seawater on the grey ruptured walls and storage tanks. Each Chinook helicopter dumps 7.5-ton loads of water on the Fukushima Daiichi complex’s Unit 3 reactor, but the water is scattered by the wind, and hardly any of it reaches the damaged reactor. Within two days the mission is aborted after radiation levels are deemed too high to proceed safely. We never hear from the pilots. 140,000 residents are evacuated.

The people begin arriving at evacuation centers, having left behind everything they own. The electric company won’t release the names of fifty workers soaking the fissured plant’s concrete walls in shifts in efforts to stave off nuclear explosion. Reporters in Tokyo are calling them the Fearless Fifty. Canadian journalists use the term Faceless Fifty. Scientists on BBC Radio claim their exposure to radiation – at least 250 times the acceptable level – will ensure a miserable death within two years.

A nurse begins publishing a blog of what she sees. It begins with the account of an exchange outside an evacuation centre with a man who was volunteering there. She describes the old man sitting on the ground outside, listening to the news account of the efforts to cool reactor No. 3. He must be in his late seventies. As he pulls his white mask below his creased chin, a teenager, wiping the sweat from his forehead, sits down next to him. They sit quietly for a minute. Nobody turns down the News. “What’s going to happen now?” the old man asks, looking at the ground. “Don’t worry,” the high school student says. “We promise to fix it back.” The radio reports continue. The high school student reaches out his arm and rubs the man’s back in gentle circles. With his young hands the student makes small circles in the space between the old man’s shoulder blades, then traces larger circles around his back. They sit for 30 minutes, until the boy’s mother calls him in to help move more beds. He puts his hand on the old man’s shoulder and then re-enters the centre in silence.

How can anyone repair what has happened there? Where do we even start? Is it with these small acts of kindness? What does the dharma have to offer us in confronting our addiction to massive amounts of energy and a growth-based economy that has outgrown the limits of the biosphere?

Will this catastrophe in Japan change us and lead to a more innovative, caring and interconnected way of living? Will the outbreaks of altruism and civic enthusiasm propel us to take similar steps? Will we demand ingenious forms of accountability? I decide definitively not to cancel my ticket to Japan. I need to see what I can learn about a Bodhisattva path through the lessons that Fukushima offers.

The most recent news I have is from a Tepco statement. Utility workers found that radioactive water was pooling in a catchment next to a purification device. The system was switched off and the leak appeared to stop, but the company said later it discovered that leaked water was escaping, possibly through cracks in the catchment’s concrete wall. It was reaching an external gutter.

I walk into my small wooden loft in downtown Toronto and over to my computer, behind which sits a vase of dried cherry blossoms and a statue of a Bodhisattva with many arms. She has a thousand arms to serve and in each hand a different tool. The path of compassion requires tools, and every Bodhisattva is depicted with a tool. I have a few tools: only a little money, a love of the dharma, and a deeper love for the Japanese people. I want to learn more about this crystal ball. I’m not in a position to hand out blankets house people, or show up with other grand gestures. I can’t even speak Japanese. And, I have an eight year old son at home that needs me. I’m showing up to learn. To meet people. To document what I see. How does change happen?

I go online and order a Geiger-counter, and then I surf the blogs with a thousand other concerned Buddhas.

[K]yoto in April is cold and colorful. I walk through gardens where my heroes Basho, Dogen, and even Gary Snyder walked. I let go of what I think and how I do things. I experiment with new routines. I feel like all these great people stand behind me in time, like the widening wake behind a boat. Are these the same paths Basho walked when he wrote about illness and cherry blossoms? Is that the hall that turned Gary Snyder toward poetry as an ecological practice? I’ve undertaken this pilgrimage to help me re-imagine my life. It’s not that I was in bad shape or feeling stuck; in fact I’ve been quite content lately, but I realized after the march 11 tsunami that there was a deeper place to go in my own practice that I could only intuit. The world is asking more of us.

I sit in meditation every morning at Ryosen-an, a Zen temple in the stunning Daitoku-ji complex. Taiun Matsunami, who leads the meditation, is in his seventies and he walks with his right foot dragging, almost a limp but more of a wobble. He rings the bell four times and the sound of a bird, something like a crow, fills the temple hall. The hall smells like straw from the tatami mats, and centuries of sandalwood incense.

Ryosen-an was founded 500 years ago as a subtemple of Daitoku-ji. Destroyed in the Maiji period (1868-1912), it was restored in the 1950s by American Zen practitioner and writer-translator Ruth Fuller Sasaki, a pioneer of Zen practice for Westerners in Japan. She invited Gary Snyder to practice here; it’s through his poems and writing that I decided to include this temple in my pilgrimage.

Ryosen-an was founded 500 years ago as a subtemple of Daitoku-ji. Destroyed in the Maiji period (1868-1912), it was restored in the 1950s by American Zen practitioner and writer-translator Ruth Fuller Sasaki, a pioneer of Zen practice for Westerners in Japan. She invited Gary Snyder to practice here; it’s through his poems and writing that I decided to include this temple in my pilgrimage.

Gary Snyder wrote about practice here: “In Zen there are only two things: you sit, and you sweep the garden. It doesn’t matter how big the garden is.” The sky is crimson, then pink, then indigo. After an hour of sitting Matsunami uncrosses his legs, rings the bell twice, and we stand up, bow to the altar of flowers, incense and a ceramic bowl of water. He takes a few minutes to rub his legs and then bows deeply before chanting the Bodhisattva Vow. His voice is low and grumbles through the room. We bow a last time and I follow him outside.

“Take a wood basket and come with me.” He turns toward the moss garden, his wrinkled hand leans into his cane. We walk past a thin straw broom, which he hands to me. “Kneel into the moss and pick out the maple shoots. If any birds picked away the moss find the missing small pieces, turn them over, and put them back where they were.” I kneel in the moist green and feel the dampness with both hands. I carefully place the wooden bowl on a rock beside me and then begin weeding the maple shoots. The shoots are thin and young and remind me of cutting my son’s fingernails in his first three months when they were soft. A middle-aged monk with black-rim glasses weeds next to me while two lay-practitioners sweep the rock walkways.

“First meditation. Then this. This is Zen practice.” Matsunami leans into his cane. I focus on the endless moss. “Zen is taking care of things. Taking care of things together.” I work for an hour, filling my wood bowl with twigs and shoots, listening to the sounds of birds in the massive cedar trees over the wall, my spine enjoying the squatting and stretching.

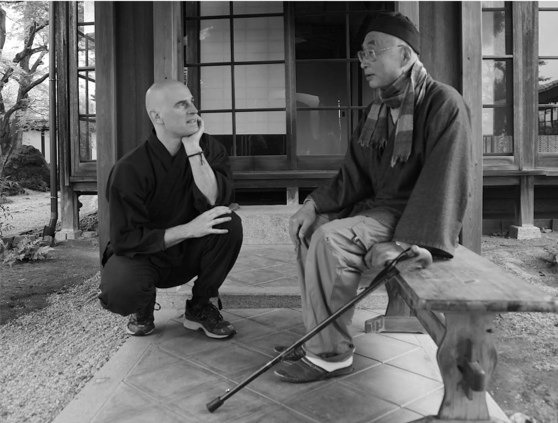

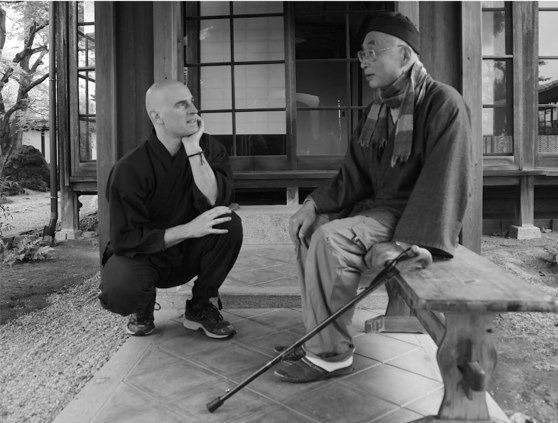

A temple bell rings in the distance and the others pick up their things and carry them back to the garden shed. My arms are relaxed. Matsunami bows and the others leave. He motions me over to a wooden bench where he sits and looks out at the garden. Again the temple bells ring in the distance. Matsunami looks right at me with the pools of his eyes. We just look at each other.

A temple bell rings in the distance and the others pick up their things and carry them back to the garden shed. My arms are relaxed. Matsunami bows and the others leave. He motions me over to a wooden bench where he sits and looks out at the garden. Again the temple bells ring in the distance. Matsunami looks right at me with the pools of his eyes. We just look at each other.

“Why are you in Kyoto?”

“I’m here to practice, be on pilgrimage, and think more deeply about the Bodhisattva Vow.”

“The vow?”

“The vow to serve all beings.”

“Do you know what that is?”

“I’m learning.”

“It can be translated as this: working together. We need to work together. Awake. We need to work together because the gap between rich and poor, educated and uneducated is growing too large.”

“Why are you limping?” I ask cautiously.

“I have cancer. In my hip. Two operations in three years. It’s very painful. I am pessimistic about my future.” He stops talking and we look at each other again. The birds pass overhead. I want to reach over and put my hand on his thigh. He rubs it himself. I hold his gaze a little longer and he looks back at the garden. “In Zen we take care of things. Each thing.”

He picks up his cane and stands. I take it as a sign to go and I don’t want to hold him up so I make my way, reluctantly, to the wooden entrance gate. I slide it open, turn and bow. He doesn’t bow. He says, “Come here, I want to show you something.” I follow him down a long outdoor corridor. In a hidden corner, reaching up against a white plaster wall, there is a hydrangea, all pink and white and heavy. “I planted this thirty years ago.” I lean in to smell it but he says it doesn’t have a scent.

We stand together. A monk further down the path is sweeping. Matsunami looks right at me again. He holds my gaze while he rubs his left thigh with his fist. I bow and turn to leave but he motions me to walk in front of him. As we’re walking he whispers, “What is your understanding of emptiness?”

“This garden,” I say unexpectedly, “…and love.”

“Christian love?” He asks quickly.

“This love. Being here together.”

“Good. Taking care of things.”

I turn around and bow deeply. He returns the bow. I bow again and unexpectedly my eyes well up as I watch him bow. He bows deeply, as if his entire life of practice were condensed into this one bow. I bow again and turn to go. This time he doesn’t stop me, though when I look over my shoulder he is standing at the gate, waving. The wind blows through the old pines and the monks in the monastery next door are sweeping the garden pathways and fixing an old fence. There is something pure here, though I never use that word because it’s something I think we reach for too easily. That’s really what this place is about – letting go of the seductive illusion of purity and embracing the deeper and more profound purity of impermanence and ongoing natural transformations. In other words, it’s the purity of taking care of what’s real: the body suffering from cancer, moss that has been knocked out of place, our complex relationships with one another. In some ways the homeless families of Fukushima are as far away as the sun. In another sense, this space is making me rethink the roots of everything I think.

Thinking about Gary Snyder here at the Daitoku-ji temple I realize again how pilgrimage is about shedding old stories and remembering the ones that are important. My son is important. My community is important. Taking care of this body is too. “Zen is taking care of things,” Matsunami said this morning.

The Bodhisattva vow is a promise to include everything. Here is the April rain in Kyoto and here is the denim coat I’m zipping up. The morning worries mix with cherry blossoms while people slowly come out of their antediluvian houses before the Japanese dawn, with the monks up the hill sitting still in black robes. Sloped tile roofs collect rain and silver, and it all floats around the quiet street down into my legs walking into this fog and I can’t exactly see the map but I stride out the door. We are learning the hard way that what we are committed to as a world of seven billion humans is no longer sustainable and hasn’t been for the past century. We can’t see into the future. We discover the world by making it.

[T]his summer in Cornwall-On-Hudson in New York State, I painted a Japanese paper scroll with a thin brush and India ink. I glued it to the thin base of a lantern. It was the night of the Hiroshima memorial and also an evening where we practiced the Obon ceremony in which we remember those who we’ve loved and have died. I imagine the leaves whipped off the trees, the trees melting into light, a t-shirt on a young girl melting plastic into her deforming skin, lesions left like holes on the soil and in people’s hearts. The uncoiling sound of complete destruction. Disfigurement. Everything that is right, exploded.

With my teacher Roshi Enkyo O’Hara and the sangha of the Village Zendo, I drive at sunset to take lanterns out to a river near the retreat centre and let them go in the slow dark currents. I stand in the river with Roshi next to me. My lantern has my uncle Ian’s name written across it with long brushstrokes and the names of some Japanese bloggers who died. The one next to me has a painting of Amy Winehouse who died a week earlier. I drop my lantern into the small crevice between two boulders and the water picks it up and pulls it away. The river carries glowing lanterns around the bend and off in the distance as the sky carries the long sirens from summer training session at Westpoint Military Academy. This river is another way we can practice something that outlives death. My uncle Ian and the 16,000 Japanese who have died so far are carried away in the glow of the lantern. No matter what we build, give, create, and love, we all go the way the river goes. We chant the Heart Sutra. Gone, gone, gone beyond. We brush off mosquitoes and watch each other watch the lanterns sailing off. The dead are just my dreams now. Gone.

And actively here.

Michael Stone is a Yoga and Buddhist teacher and activist from Toronto, Canada who arrived on a pilgrimage to Japan in April of 2012 to learn how the Japanese were responding to the aftermath of the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami. In addition to this essay, his trip resulted in a film project called REACTOR, directed by Ian MacKenzie (One Week Job; Sacred Economics, including interviews with Rev. Kawakami Takafumi, of Shunkoin temple, Kyoto; Mizuno Toshinori of the avant garde art collective Chim↑Pom; Dr Imanaka Tetsuji of Kyoto Research Reactor Institute; Ogura Keiko of Hiroshima Interpreters for Peace; and Fujii Hanamaru, Tokyo illustrator/writer of The Power Story. Key question: “How can we embody the Bodhisattva vow in these times?” See http://www.reactorfilm.com