Spared the fate of many Japanese cities during the War, Kyoto is the standard bearer for the country’s glorious past: a repository of ancient traditions passed down through generations, with the support of networks of businesses that often boast connections to the imperial court long since its relocation to Tokyo. One such vestige is that of characterful kyo-machiya townhouse architecture, that becomes ubiquitous as you venture off the city’s major boulevards and enter into the sanctuary of its narrower passageways.

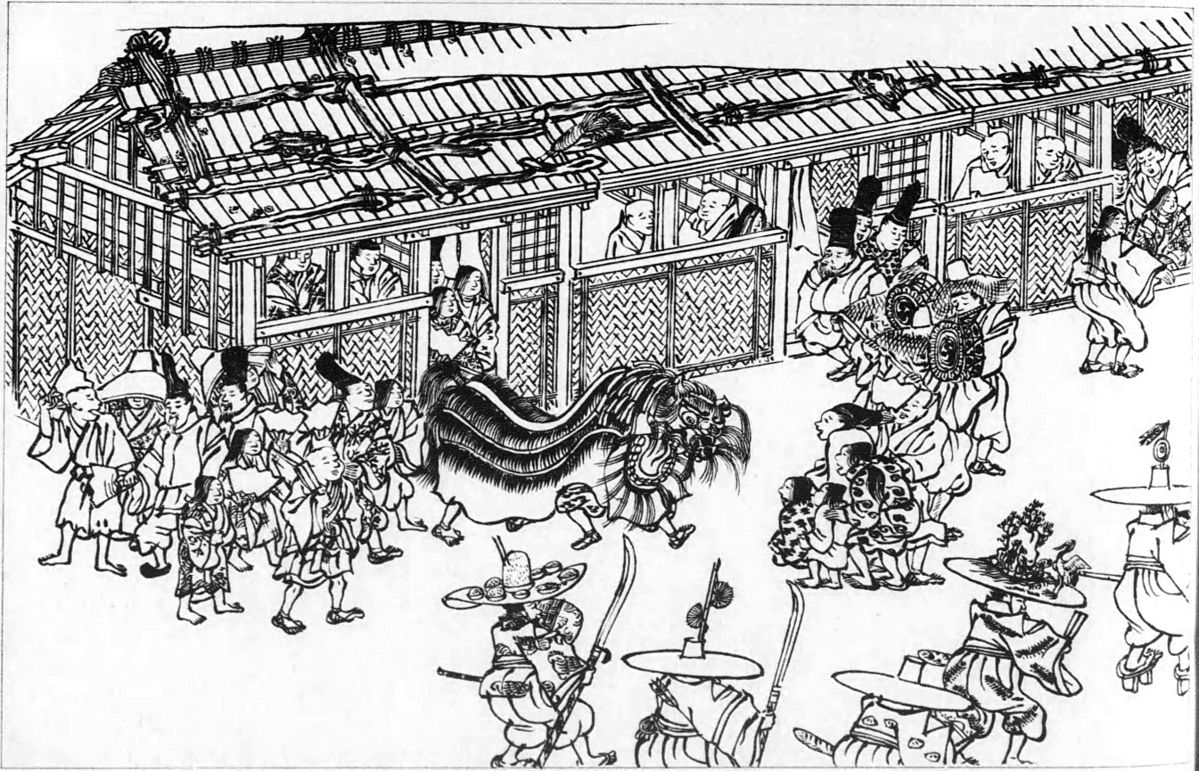

Development of kyo-machiya can be traced back to a millennium ago, during the latter years of the Heian Period (794-1185). Though little architecture from this period is extant, an elaborate picture scroll, the “Illustrated Scroll of Annual Festivals” (Nenju Gyoji Emaki), depicts what historians commonly refer to as machiya’s precursor. Rows of simple, gable-roofed, wooden structures, deep rather than wide, line the path of a festival procession, with purpose-built platforms for watching the spectacle. It is likely that many of these early street-facing buildings were the first combined business-residences to develop outside of designated market areas. What’s more, you can see the interiors clearly divided by earthen and raised wooden flooring in a spatial arrangement that is remarkably familiar today, except that it is nowadays lined with tactile tatami straw mats.

Certain features emerged that would become synonymous with machiya: for example, the often removable, latticed façade which allowed daylight to filter in while maintaining privacy of the inhabitants when not conducting business (which would ordinarily take place in the front end of the building). These houses, however, were continually adapted to meet social, commercial and—particularly during the tumultuous medieval period— security needs over the following centuries. Ease of assembly was highly desirable when devastating fires would periodically raze whole neighborhoods to the ground. The introduction of Zen Buddhism heralded an appreciation for garden design and incorporation of elements of the tearoom into a residential setting. Those engaged in certain crafts required necessary modifications: weavers in the western Nishijin district, for example, needed high ceilings for their looms. As a result, everything from plot size to materials used in kyo-machiya varied widely. It was not until the Edo Period that construction methods were standardized, which essentially made elements replaceable and transferable.

Some 40,000 kyo-machiya still stand in Kyoto but are being erased from the cityscape at an alarming rate: on average two to three every single day, according to 2016 statistics. Many lie vacant and punitive inheritance taxes are a powerful incentive for inheritors to sell the land to developers, who in turn clear it for hotels, car parks and condos. What few appreciate is that these losses are irrecoverable in more than one sense—1950s building codes made the use of some construction techniques unique to these homes impossible in new builds. As a result, the skills associated with such are being lost (see our interview with clay wall specialist, Emily Reynolds in KJ89).

Hachise is a realtor that has come to the forefront of a growing city-wide endeavor to restore kyo-machiya. Starting in 2000, the company began to acquire properties for renovation and resale, hoping to spark renewed interest among locals who may otherwise have thought of machiya as stale relics of the past. Hachise’s approach is to preserve the integrity of a building but with adaptations that make it more attractive to those who may have concerns regarding the upkeep and comfort of such homes.

Encouraged by the inbound tourism boom of the past half-decade, Hachise launched KyoTreat: a selection of now twelve, luxurious, fully-furnished properties for monthly rental that soon found popularity among foreign visitors keen to live “as the locals do.” But Hachise also realized that there was a market for second homes emerging, not just among high-flying Japanese urbanites, but from a new class of repeat overseas visitors in love with the city. They mobilized a multi-lingual team and resources to facilitate this growing demand, offering management and leasing services for when the owners are out of the country.

Among those machiya that Hachise has transformed is Gojo Tenjin, one of the company’s most in-demand properties when it joined the KyoTreat line-up. A mere block away from the thoroughfare of Gojo Street, it is one of a group of six terrace houses in a small roji alley off-limits to traffic: an oasis of seclusion. The owners, Roland and Hisako are delighted with the location: “You can see the upper floors of Gojo’s modern buildings but, believe it or not, it is very quiet here.” The couple lives most of the year in San Francisco, during which time Hachise leases it to holidaymakers.

Most of the houses on the roji were built at around the turn of the 20th century. While Gojo Tenjin had undergone some alterations by its previous owners, Hachise preserved many of the key features. The walls are a clay plaster mix with washi paper to add subtle texture to the refurbished interior. Towards the rear of the house, Roland points out where the small interior garden once housed a well that the previous family and perhaps the whole roji would have depended upon. “There is history; there is a story,” says Roland. “All these things make it very interesting for me. I am glad that Hachise is preserving these kinds of properties.”

The couple’s own style is also infused into the small details of the house, and it would seem to play a significant part in attracting new tenants. Roland is a photographer specializing in architecture, and his work can be found adorning the walls.

Hisako, a native of Iwate Prefecture, recalls her initial skepticism about the property: “Honestly, when I heard about the machiya… I thought, I had already experienced living in old houses in Japan and did not like the idea,” she admits, “But what Hachise did is remodel this into what I feel is a new, modern house.”

One more recent innovation in machiya living is that of the underfloor heating system. Many a Kyotoite who has lived in a traditional home will complain of the bitter winters, and how the cold draft would send them to the refuge of the kotatsu: a table set over a sunken floor that is covered with a blanket and equipped with a heating element beneath. In addition to improved insulation, the underfloor system, that distributes heat more evenly and efficiently, does much to improve comfort levels—perhaps not a surprise, then, that Roland and Hisako considered this a necessity long before they moved into Gojo Tenjin. Although the return to the house for only a short period each year, they are well-acquainted with their neighbors, many of whom were born in the roji but look out for them as they would longterm residents. The warm welcome they receive upon their return is a joy, they say, as is knowing they always have a seat saved for them at their local takoyaki joint.

Hachise’s work helps to preserve not only the legacy of the city’s architectural history but also the tightknit community fabric that the kyomachiya lifestyle fosters. Hachise’s Executive Director, Nishimura Naoki, expressed this and more when KJ sat down with him to talk about his experience and aspirations for machiya culture in Kyoto.

Can you explain your personal relationship with kyo-machiya?

The first machiya that we lived in after my wife and I got married had a long, narrow, one-by-twenty-meter roji that led to the entrance. Despite the path being too narrow to even open an umbrella, having this hatazao (literally flagpole) stretch meant that we had outdoor space immediately outside the property where the children could play, without worrying about speeding cars. Twenty-meter races were daily rituals, as was drawing on the ground with chalk. It was their playground.

When we bought the house, a lot of the traditional elements were already lost. Traditional machiya have latticed bay windows; ours had been substituted with tiles. We wanted to restore that element but decided to do it in a way that would still fit our modern way of living. We also adjusted the height of the windows to protect our privacy while allowing soft light to come in.

Can you describe how the features of machiya changed through history? Have they Westernized?

After the Meiji Restoration, Japan saw a trend in what we call “colonial” architecture. Jo Niijima’s* house still impresses me, and a lot of Japanese including my wife had gotten used to the idea of living in a Western-style house. Our house didn’t have the large pillars that are typical of machiya, but we had the staple walnut flooring, plastered walls made from natural material. The thing is: Western and modern features go quite well with machiya. We had a chandelier hanging from the stairwell. Nowadays, it’s not unusual to see Italian restaurants built in machiya, for example. Do you find any differences living in Western-style homes as opposed to kyo-machiya? I was born and raised in a Western style house, and by comparison I feel a sense of ajiwai in machiya: it has “flavor.” When things break or get dirty in Western-style buildings, it just feels like it’s worn out and needs replacing, but here, you feel a kind of affection for even the finger marks on the walls or a scratch on the floor. It’s difficult to put into words; you feel proud of the house including all those imperfections. Those imperfections make it all the more valuable.

Something particular to machiya is the marked exposure to the changing seasons, especially with the presence of tsuboniwa courtyard gardens. How about in your house?

It’s not often when you see a toro stone lantern covered in snow, and that was something special in the winter. We had a momiji maple in our tsuboniwa but because it was in the shade, the leaves would change one month later than outside. It’s not how one usually appreciates the autumn leaves in Kyoto, but I guess it wouldn’t even have been on my mind were it not for the tsuboniwa. The same goes for the light from the window in the stairwell that would refract through the prisms of the chandelier and scatter over the front room. It would only happen during a short time between 7.30 to 8 AM in the spring and autumn. I felt lucky, privileged to be Japanese and living in a machiya.

What are your aspirations for the future of Hachise and machiya culture in Kyoto?

As a company that strives to preserve machiya, we want to do more than just build and sell. We would like to own and manage. We have been operating and managing vacation homes since before they gained popularity. We also have a few tenants renting our properties, and one co-working space. Converting visitors, who experience machiya living short-term, into actual buyers: that would be best for Kyoto. We hope to create spaces where people can connect. People who are fond of machiya are interesting people in their own right—imagine them gathering and coming together in order to support the development of machiya culture. We aim to run a sustainable business model, one where we can share machiya as well as culture.

*Jo Niijima (1843 – 1923) founded Doshisha English School, later renamed Doshisha University. His residence, which blends Japanese and foreign architectural styles, still stands on the east side of the Imperial Palace.

This article is the first in a four-part series in partnership with Hachise on kyo-machiya and innovation in Kyoto’s traditional Japanese architecture.

Photographs by Daniel Sofer and courtesy of Hachise. Interview by Ty Billman & Kyoko Yukioka.