[T]he ancient craft of bronze mirror-making dates back to 2900–2000 BCE in China, Egypt and the Indus Valley. Bronze, a highly-reflective alloy of copper, tin and lead, can be either gold or silver in color. Bronze mirrors became popular and were produced in large quantities during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–24 AD) in China. Usually circular, they later evolved into a variety of forms, from oblong to octagonal.

As use of bronze mirrors became widespread in China, the ancient craft of mirror-making spread to neighboring Korea and Japan. The Emperor Cao Rui and the Wei Court of China reputedly gifted numerous bronze mirrors (then known as shinju-kyo in Japan) to Queen Himiko of Wa (Japan). During excavations of the Kurotsuka kofun (tomb) in Nara, archeologists discovered 33 similar bronze mirrors dating to the 3rd-7th centuries.

In ancient Japan, mirrors were especially revered as rare and mysterious objects. In 1339, Chikafusa Kitabatake wrote (in the Jinno Shotoki) that they were seen as a “source of honesty” because they reflect “everything good and bad, right and wrong… without fail.” In fact, one of Japan’s three most important imperial treasures is a sacred mirror called Yata-no-Kagami.

In a story that is central to Japanese mythology, this bronze mirror was key to coaxing Amaterasu Omikami (the Sun Goddess) out from the cave she had retreated to after a skirmish with her younger brother (Susanoo, the Storm God). (While one deity gave an amusing dance performance, another held up the mirror to deceive her into believing there was another goddess who could outshine her). It is believed that Amaterasu resides in the Yata-no-Kagami, housed today in Ise Shrine, off-limits to the public in Mie Prefecture.

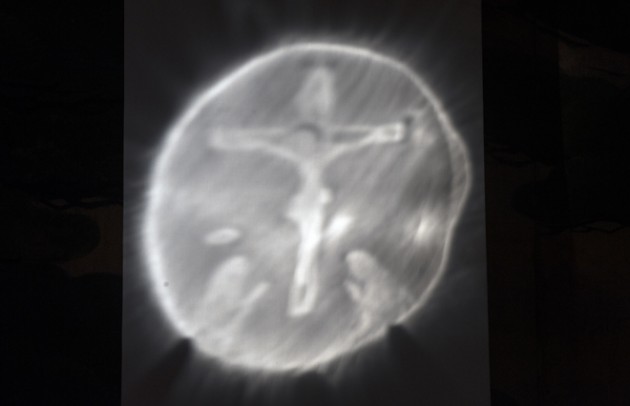

In Japan, bronze mirrors are known as magic mirrors, or makkyo (魔鏡). One side is brightly polished, while an embossed design decorates the reverse side. Remarkably, when light is directed onto the face of the mirror, and reflected to a flat surface, an image magically appears (usually the one featured on its back). While the metal is completely solid, the reflected image gives the impression that it must be in some way translucent. For many centuries, the ‘magic’ of these mirrors baffled both laymen and scientists.

The currently accepted explanation for this phenomenon is that during its construction the mirror’s surface is scraped, scratched, and polished, then coated with an amalgram of mercury, thereby causing stresses and “preferential buckling” into convexities of a scale too small to be observed by the naked eye, but matching the pattern on the back of the mirror.

Kyoto Journal sat down with the man rumored to be the last remaining makkyo maker in the world — Yamamoto Akihisa — and his friend, Yoshida Hisashi. Mr. Akihisa is descended from a family of mirror makers based in Kyoto. Mr. Yoshida works with Shinto shrines and makes traditional Shinto clothing. They collaborated to organize a fascinating exhibition displaying Mr. Yamamoto’s mirrors at Impact HUB Kyoto in June 2013.

KYOTO JOURNAL: We hear that you are the only remaining makkyo mirror maker in Japan. How would you introduce yourself?

YAMAMOTO AKIHISA: I’m a mirror maker. Sometimes I make makkyo mirrors and sometimes I make devotional mirrors for Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples. As far as I know, my company is the only one in Japan producing makkyo mirrors. For shrine and temple mirrors there are probably a few other places in Japan.

My father and I are the only craftsmen in our company who make mirrors for religious purposes. Although my father can make makkyo, he is currently in charge of producing shrine mirrors. Our company also makes devotional items for butsudan (household Buddhist altars), as 70-80 percent of our business. I make all my mirrors by hand, which is very rare these days.

Did you always know that you would make mirrors?

My family wanted me to pursue what was right for me. I actually chose this profession myself. I felt like it was my life mission to continue the craft, and I have found importance and meaning in my job.

What is your average working day like?

Normally it’s from 9 to 7pm but on busy days I work until 9 to say 10 or 11 — maybe even midnight. Past midnight I lose my focus and get tired. Usually I make mirrors, but I’m often asked to [repair] old mirrors or mirrors that have gizu [scratches] and need to be cleaned. Cleaning old mirrors is challenging because they are thin. I have to be careful.

When did you first begin making makkyo?

Ten years ago. My grandfather rediscovered the technique and was the third generation of makkyo makers in my family, which makes me the fifth generation. The first generation of Yamamotos started it as a family business.

The skill and technology was passed down to my father and then to me. When I started learning about makkyo, my grandfather had already passed away, so I learned the skill from my grandfather’s younger brother. It took me three to four years to master it, and to be satisfied with the result.

Your grandfather rediscovered the technique… could you expand on that?

My grandfather received a commission — from Kyoto University, if I recall correctly — to make a makkyo mirror. People wanted to know if it was possible to make makkyo in present times. My grandfather had been actively involved in crafting mirrors for Shinto shrines since even before the Meiji Restoration (1868), and he had a sample makkyo, so he was already familiar with the method, although he hadn’t attempted to reproduce one himself until then.

So, with just this one sample and through trial and error [recalling aspects of how his father had made them, despite not having been taught the details], my grandfather rediscovered the art of makkyo-making.

Do you think of yourself as an artist or a craftsman? Do you make a distinction between the two?

Although within the traditional crafts industry there are some who call themselves craftsmen, and some who call themselves artists. I think of myself as more of a craftsman. Historically craftsmen weren’t allowed to exhibit their work, but now, we can do so outside of the regular shrine or temple context. I allow my mirrors to be seen outside of a sacred context, but only in exhibitions or in private settings. I do this because I possess a special skill and others need to know that it exists [for it to continue]. In my experience, artists express their own thoughts and feelings while craftsmen make commissioned work. For a craftsman like myself, it’s more about making the object and the technology and skill behind it.

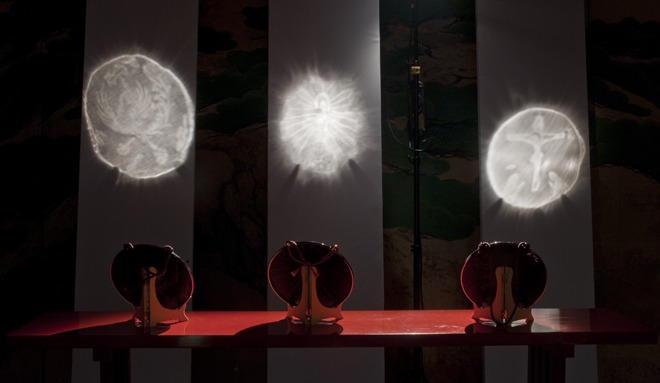

In the case of the Impact HUB Kyoto exhibition, I was approached by an artist, Mr. Yoshida, who wanted to collaborate with me to hold an exhibition of my mirrors. Therefore, I made and presented the mirrors as a craftsman, and Mr. Yoshida curated the installation.

YOSHIDA HISASHI: For this exhibition, it occurred to me how unfamiliar the younger generation is with traditional industry. Their way of seeing these objects is more as artwork than having a devotional purpose. However, making sacred objects requires sophisticated craft work because they are being delivered to the kami (gods).

While Yamamoto-san considers himself more of a craftsman than an artist, I am happy that his works could be seen as art at Impact HUB Kyoto.

YAMAMOTO: When devotional mirrors are displayed in Shinto shrines, they are either hidden from the public eye or placed where they can only be seen from the front. At the exhibition I wanted to give people the opportunity to see both sides of the mirror.

Your company’s mirrors go to both Buddhist temples as well as Shinto shrines, however, I heard that you were a Shinto mirror maker. How would you identify or define yourself and your work?

When Buddhism came from the Asian continent, it was incorporated into Japanese culture alongside Shinto. Mirrors were already customary in Shinto shrines, and the application was later extended to Buddhist temples.

YOSHIDA: While Shinto is the native religion of Japan, we Japanese have been receptive to other religions, particularly Buddhism. The underlying belief of Shinto is that there are like eight million gods. There’s no real distinction between those eight million gods and Buddha. In other words, religion in Japan is polytheistic, rather than monotheistic. In the same way, there’s no clear distinction between the mirrors for Shinto shrines or Buddhist temples, nor those with the image of Jesus Christ.

They are all religious in nature?

YOSHIDA: Yes, but actually makkyo are rarely sent to Shinto shrines, they are usually sent to private homes.

YOSHIDA: Makkyo project images, of a saint for example. In Shinto belief, the gods dwell in our natural surroundings, like in trees or stones, which means that there is little imagery of the gods themselves in shrines. Therefore, it’s not appropriate to have makkyo mirrors in Shinto shrines.

YAMAMOTO: For Buddhism, there are many different types of temples. Some temples are a mix of Shinto and Buddhism and have a yashiro [a small shrine in their precincts]. These temples place a mirror inside the honde [the main hall of the temple] or in front of the Buddhist statue.

Mirrors have many uses — they were put in graves, ten mirrors placed around people’s heads, especially in kofun — used as gifts, as religious ceremonial tools and sacred goshindai [“god-dwelling objects”], but why do you think they’re so special? Why do they have this long tradition and so many uses?

YOSHIDA: It’s believed that mirrors in Shinto shrines, for example, are placed in cases where people can see their own reflection when they come into the shrines to pray, so that more than about seeing the gods you can see yourself reflected in the mirrors and it becomes about seeing a clear image of yourself.

At the HUB Kyoto exhibition, you could actually see your face on the back of the mirror. Is there a distinction between mirrors with that reflective quality on the back and mirrors that don’t have that?

YAMAMOTO: The traditional style for a mirror does not have a clear reflection on the back. People from Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples prefer this style because they want to preserve and continue the traditional craft. However, it’s more time consuming and more expensive to make.

When you make a work that’s going to be a goshindai, is it a different process? Is there something you do differently in the case of a sacred object — washing hands or wakanai [praying] — compared to a mirror that might go into a house?

There’s not much of a difference when making mirrors for personal homes or as goshindai. However, when I go to Shinto shrines, I wear shiroshozoku [a white cloth] because it’s being delivered to sacred ground.

When you make a mirror for commission, do your clients specify what they want or do they ask for your ideas?

Both. There are cases where the client says what they want me to make, and there are times where I’m asked to offer my own ideas. When the client wants a special image I ask a painter to make a design and then show it to the client.

Generally, I show my clients many different samples and designs from what I already have and then make a suggestion. This is more common because I already have the molds, so it’s more cost-effective. A new design costs about ten times more, and takes about two to three months to finish because everything has to be made from scratch.

While it’s not very common for me to make the whole thing from the start, I prefer that because then both my technology and my art can evolve. In order to continue and develop my craft, I want to have the opportunity and time to devote to [the whole process of making] one piece. So, it’s kind of a dilemma.

You said earlier that you think of yourself as a craftsman…

Ideally I would like to devote all my time to making mirrors so that I could constantly develop my craft. In that sense I want to be a craftsman. In reality I’m open to my work being perceived as art objects, if it means it will reach a larger audience and public. When I did the Impact HUB Kyoto exhibition, I saw it as an opportunity to promote my work and reach a wider audience. I want to show people mirror-making because it is a fading traditional craft and people are not aware of it.

What is your goal as mirror maker in this fading tradition?

I want to pass on this craft to the next generation of craftsmen. I want to find a way and build a place that expresses the importance of mirror- and makkyo-making to the next generation. It’s important to pass on this craft because once it’s gone, it will be really hard to discover again. If the craft of mirror-making is not continued, not only will mirrors cease to be made, but the history of mirror-making and the many generations of people who have supported and developed this craft to where it is today might be forgotten as well.

Do you want to pass this on within your family or to another student? The people in your family who were skilled mirror-makers were all men. Could a woman be a mirror maker?

My father is against taking in a student/ apprentice because my grandfather had a student who learned makkyo-making from him and the student took it to Shikoku island with an intention geared towards shogyoteki — for commercial endeavors — which is different from my family’s. I don’t have any children of my own. I am not against the idea of women inheriting this craft, but I believe it would be difficult for women to take on the profession and work closely with Shinto shrines. However, if I had a daughter, I would gladly pass on the craft to her.

If a student becomes independent, there’s a problem that the student of course sells his work at a lower price than his master and that causes an imbalance within the industry. People prefer a lower price so a lot of commissions would tend to go towards the student. It’s a contentious issue, training a student and having that student become independent.

If the competition becomes solely about pricing then it’s really tiresome. But if the competition becomes about raising the technology or enhancing the craft then that creates good competition.

It sounds like there is a different sense or feeling about the craft in your family. Why is it important to you to continue this craft?

I’m not simply making mirrors as a source of income. I believe it is a really important craft and I want to pass my knowledge about the craft on to other people. At the Impact HUB Kyoto exhibition we showed images of Buddha and Jesus Christ. As a Japanese I don’t see the distinction between “that’s Buddhist” or “that’s Christian’ because our culture accepts all religions. I didn’t know how non-Japanese people would see the exhibition, but I think that’s an important thing — to encompass and accept all religions — and that’s probably what the world needs now. And that concept of encompassing and accepting all religions is a story I want to tell through this craft.

What is your happiest/ most satisfying moment as a mirror maker?

When I deliver a work, and the client really appreciates my work, whether it’s a new mirror or an old piece that I’ve repaired, I feel really satisfied. One time, I repaired an old mirror for a client and he really understood and appreciated all the dedication and time that I put into it. The client actually offered me more money than I had quoted and even though I resisted, he insisted because he really appreciated the work that I had done for him.

What is the most memorable mirror that you’ve made?

A piece that I did for a family that had just lost their dog. When they asked me to make a design of their dog I immediately said yes. It was challenging because I had never done a design for a dog and the family wanted the dog to face forward, which is technically very challenging (usually they face sideways). There were also the emotions of the family that I wanted to be sensitive to and respond to.

Hojoung “Jodie” Moon is from Seoul. She is an anthropology major at Reed College.

Translation by Masako Kaidan

Research by Lisa Yamashita Allen

Photographs by John Einarsen