Eat Sleep Sit: My Year at Japan’s Most Rigorous Zen Temple, by Kaoru Nonomura,

trans. by Juliet Winters Carpenter, Kodansha (Tokyo), 1996, 324 pp.

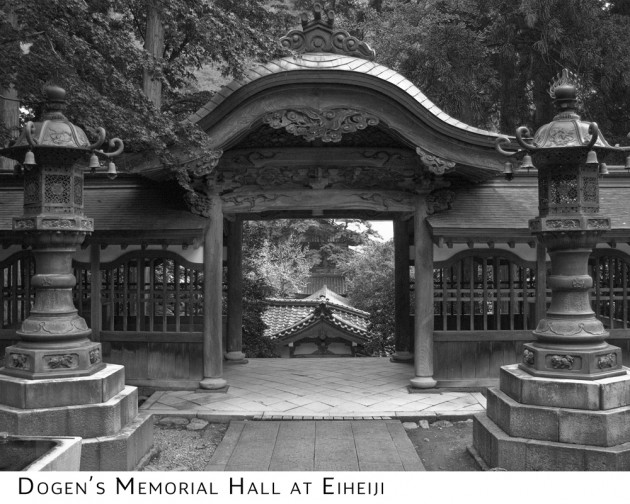

[A]FTER TURNING THIRTY and feeling somewhat disillusioned with his life at a design company in Tokyo, Nonomura Kaoru mustered his courage and left everything behind to enter into shukke — the act of renouncing the world and joining a temple. Nonomura chose Eiheiji, the mighty headquarters of the Soto Sect of Zen Buddhism, founded by Dogen in 1244 deep in the mountains of present-day Fukui Prefecture.

Eiheiji’s reputation as the toughest Zen training center in Japan is born out in this memoir. Indeed, after Nonomura passes through the Dragon Gate, the point of no return, with seven other acolytes (three of whom will end up in the hospital within the first six months), he enters a kind of “boot-camp” hell in which there is constant mental stress, bodily pain, little sleep, exhaustion, and verbal, and, at times, physical abuse heaped upon any trainee who commits the slightest breach of etiquette. All of this, of course, is aimed at annihilating the “self” of the novice. And so Eat Sleep Sit unequivocally smashes any romantic notions a naïve Western reader may entertain of life in a Zen temple.

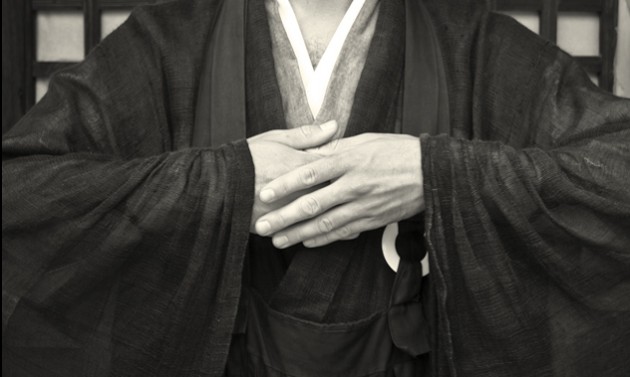

As weeks pass, we begin to get a rare window upon this virtually closed, hierarchical community that still operates on medieval principles that were laid down over 700 years ago. The value in Nonomura’s recollections is his day-to-day account of how this community operates — how monks learn, bathe, greet each other, fight off exhaustion, and practice. This would be impossible without including ample translations of the strict rules of etiquette that govern Zen life — everything from how to go to the toilet, how to eat, and even how to sleep (on your right side) — that were written down in precise instructions by Dogen. He leaves no action to chance, and learning these endless rules of etiquette is what gives the acolytes such intense mental stress. But these codes eventually become second nature, and one can see the immense influence Dogen had on Zen, and subsequently, on Japanese culture. There is always a correct way of doing things in Japan, and it is usually economical, simple, correct, attentive, and dignified — the sort of qualities that Dogen sought to instill in each act.

Japanese hold these Zen trainees in deep and affectionate respect. At one point, the monks open a box sent from an old-folks home in Hokkaido — it is filled with hand-sown rags made from scraps of old obi. An enclosed note tells them to use the rags for polishing the floors and encourages the monks to practice hard. Such gifts are not unusual. Nonomura decides to leave Eiheiji after a year, and his encounter with a taxi driver soon after he passes out of the temple gate is quite moving. He later began to write down his experiences on buses and trains on his way to work.

Juliet Winters Carpenter, who continues to expand her range of translated pieces, beautifully translates the book — especially the excerpts form Dogen’s writings. Eat Sleep Sit should be read by anyone who is curious about what real Zen training is like in Japan. It will also make a good companion to any visit to Eiheiji.

* Zen, a film about Dogen’s life was released in early 2009 and was directed by Banmei Takahashi.