Given the choice, most people would rather hear a sermon on heaven than experience heaven directly—this maxim describes a hidden quandary in Michael Goldberg’s admirable film A Zen Life: D. T. Suzuki. The Bodhisattva dilemma: if all sentient beings are saved then the Bodhisattva is annihilated—an obsolescence which ironically signals the Bodhisattva’s salvation. A spiritual co-dependence is critical to the relation between the enlightened and the sentient, between teacher and student. Moreover, if we accept the Buddhist notion that form (in this case, film) is emptiness, then has Goldberg broken a fundamental rule of Zen: Has he exalted the messenger at the expense of the message?

Perhaps…but in his film Goldberg supplies another dimension to this preeminent and prolific twentieth-century writer and philosopher to compliment the printed word. Add to this the rising tide of global alliteracy (a predilection for image over logos) as well as the tendency to prize personality over pedagogy, and a film with Daisetsu Tetaro Suzuki as its subject seems increasingly welcome. Indeed, more than Zen teaching or enlightenment or aesthetics, D. T. Suzuki pervades Goldberg’s film like an omnipotent atmosphere. Since his death in 1966, having left his human form behind, Suzuki has become an illumined emptiness guiding countless scholars, writers, artists, doctors, and priests who have followed. A video vision of D. T. Suzuki may be culturally pertinent since psychiatrist Albert Stunkard cites Suzuki’s way of expressing an “understanding which goes way beyond the words.” Words, film, and other modes of representation are often instructive but are also dispensable. As Alan Watts used to say: “Once you get the message, hang up the phone.”

Hence, in A Zen Life, D. T. Suzuki emerges as a former mortal who downplayed his realization in order to prompt a realization in others. Goldberg, while not concentrating on the Zen experience, goes a long way to help clarify the messenger, the medium. Archival film and photographs compliment a fluid narrative of Suzuki’s history, biography, philosophy, as well as recollections of many who knew and learned from this amazing and subtle teacher. It’s always astonishing what can come from mundane beginnings. Goldberg begins his film by tracing Suzuki’s humble beginnings in Kanazawa, amid a dissolving family life. Suzuki admits being a truant college student, however, as well as an avid English enthusiast he took up teaching English as a vocation, later pursuing the obvious extension of translating texts. Becoming adept at English, Suzuki worked as interpreter for Shosaku Soen, a renowned Zen Master but enlightenment eluded him. When invited to teach and work in America Suzuki postponed his departure and commitment to his work until he had achieved satori—granted, a subjective and essentially unverifiable experience. Surprisingly, Suzuki’s modest fame flourishes after the Second World War, when he was 75, and continued for the next twenty years of his life and continues to this day. Goldberg pursues several transitional themes throughout the film, such as Suzuki’s lack of serious academic study as a youth (although language and translation was to occupy him throughout his life), anti-war sentiments during the war, interest in the miracle drug LSD, and later preoccupation with Pure Land Buddhism.

Beyond basic biography, Goldberg consigns the narrative to those who were directly influenced by Suzuki’s teaching. At this point, the film takes on a different quality. What is celebrated in this noteworthy film is not Suzuki’s enlightenment so much as his articulation of what that enlightenment means. And that exegesis is reflected back upon the viewer via the recollections of those who knew and learned from Suzuki. Several scholars, artists, psychiatrists, and writers lend their reminiscences to the narrative and some will be more familiar than others: Donald Richie, John Cage, Gary Snyder, and Robert Aitken for example may surpass Albert Stunkard, Frederck Franck, or Elsie Mitchell but all contributors share a respect and gratitude for Suzuki and their observations reflect the profound influence this humble man from Japan had on them.

Luckily for the Western world at large, Suzuki appeared at just the right time—in true Bodhisattva fashion. Moreover, through his numerous publications in Japanese and English, Suzuki made his peculiar enlightenment conspicuous. Otherwise he would have perhaps enjoyed an anonymity worthy of Han Shan and a myriad host of Bodhisattvas who inhabit, as Snyder remarked, “the skidrows, orchards, hobo jungles and logging camps of America.” So, in this film Goldberg celebrates Suzuki’s role as enlightened teacher rather than an indescribable enlightenment experience.

Suzuki, although active in the US since the end of the nineteenth century, claimed that the West never took the Orient seriously until after the Second World War and many of those interviewed concur. Snyder brazenly suggests that Americans took an active interest in Zen Buddhism out of a sense of guilt for having bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which is akin to implying a causal relation between the 60s cultural revolution and John Kennedy’s assassination—which may be true. (Alan Watts elsewhere intimates that, after World War II, Christianity could not compete at the same intellectual level as Buddhism since most Christian theologians had been confined to essentially Biblical training.) In response to changing spiritual concerns after the war, Thomas Merton is quoted as contending that the West’s habitual “suspicion of other religions” has become obsolete. Hot on the heels of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung, Suzuki gave everyone permission to reorient themselves, allowing the West to revel in the intelligence of the irrational, the sacredness of the ungodly, and the beauty of the ordinary. The West’s scientific failings, Snyder continues, have hindered our spiritual depth—a typical response to a post-modern age characterized by blood and brutality. In this DVD, Suzuki emerges as a metaphor in that he exemplifies the necessary, if uneasy, marriage between religion, politics, and psychology.

Film, art, poetry, music—when considering any metaphoric work of art, the object is eventually absorbed into the subject, which is to say that art ultimately concerns the viewer more than the artist or the object d’art itself. In this regard, Suzuki is finally conceived as a “Nowhere Man” who is eternally here and now and the words Allen Ginsberg once used to describe Bob Dylan can be equally applied to him: “He was a shaman who had found a way of disintegrating in public.” Such an observation reveals little about Suzuki or Dylan; however, it shows a lot about Ginsberg and finally ourselves. In genuine aesthetic experience the object becomes transparent and we are left with the subject, the viewer. Mona Lisa, the Pieta—they’re not “there”; they’re now and here in as much as artistic objects take up residence in us. We gaze at a painting of grapes, for example, but we do not worry if they are actually sweet or sour. Any work of art or enlightened life, and this provocative film, is finally about the viewer. Contrary to the cartoon Lennon character in Yellow Submarine, it takes a Nowhere Man to lead us somewhere.

As a Nowhere Man, Suzuki was the perfect catalyst for an emerging Western strata of neo-transcendentalists, heirs to Emerson, Thoreau, Whitman, yet burdened with a psychological stigma as America gazed West across the Pacific and envisioned an Asia in ruins. Moreover, in the film, there is a sense of archival urgency in that all the participants interviewed for this film are themselves ancient, which foregrounds the issue of spiritual legacy. We may be witnessing a gesture to a lost time or last time, a spiritual environment which no longer exists, a metaphysical context which has become outdated, a glimpse into a freshly forgotten past, a nowhere relocated in a meaningless somewhere.

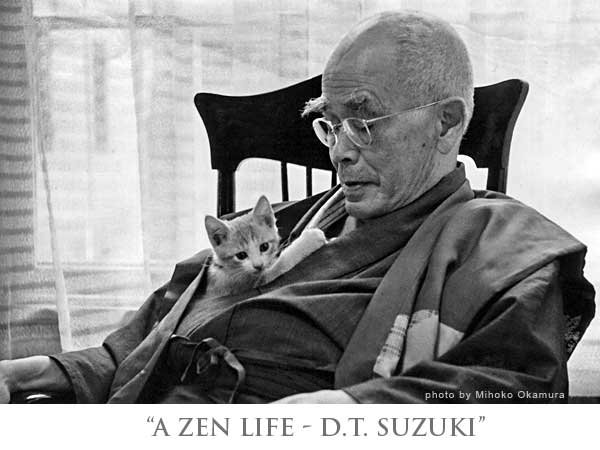

Goldberg concludes his film abruptly with a brief account of Suzuki’s sudden death at age 96 but, as Mihoko Okamura points out, “there seemed to be no demarcation between Suzuki’s life and death”—a sentient continuum undisturbed by animation or demise. And that’s where Goldberg deposits the viewer: at a fictitious end. Upon reflection, Suzuki’s posthumous reputation may fall victim to Gertrude Stein’s assessment of Ezra Pound: “…a village explainer—excellent if you’re a village, but if not, not.” Today, however, residents of a shrinking and percolating “global village” may be in desperate need of such an explainer as Suzuki (or Pound for that matter); indeed, on camera Huston Smith reflects that Suzuki offered such incredibly rich “resources [for peace] that it would be a tragedy to lose [them].”

Finally, an enlightened Suzuki does not strictly serve the academy or the institution; instead, he sets an example of what is available to all people. Like a latter-day mystical Falstaff, Suzuki’s own satori was neither here nor there; more important was the enlightenment he caused in others. Suzuki was remarkable in that he made others remarkable and, as such, A Zen Life is as much about those Suzuki animated, as it is himself. As the film progresses, Suzuki soon fades into the background: he becomes the larger context forged from the memories and accomplishments of those he inspired and who here reminisce. The Nowhere Man begets now-here children.

After watching A Zen Life, despite the contradictions inherent in attempting to film the unfilmable or articulate the inarticulate, the viewer feels spiritually and intellectually cleansed which, in our media-drenched age, is no small feat. Given Suzuki’s admonishment to Donald Richie, that “you can’t put such a big object [Zen] into such a small package [representation, form, or film],” Goldberg has nevertheless confronted this overwhelming challenge with grace and poise. Highly recommended.

A Zen Life: D. T. Suzuki, Executive Producer and Director Michael Goldberg, Co- producer John Wittmayer, International Videoworks Inc., Project of Japan Inter-Culture Foundation, 2006, 76:50 mins, (http://www.ivw.co.jp/)

Preston Houser is a longtime resident of Kyoto, shakuhachi master, and former KJ Reviews editor. Listen, at Kyoto Meditations https://keidokyoto.wordpress.com

Images sourced from Flickr.