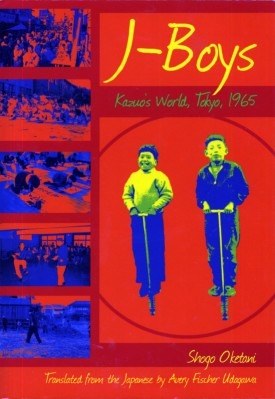

J-Boys: Kazuo’s World, Tokyo, 1965, by Shogo Oketani, translated by Avery Fischer Udagawa, Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press , 2011. Paperback. 214 pages.

A work of Juvenile Fiction, aimed at the U.S. Middle Grade audience, J-Boys follows 9-year-old Kazuo and his younger brother Yasuo around Tokyo’s Shinagawa Ward from October 1965 to April 1966.

The book is divided into six monthly sections: the first four each contain three or four related short stories or vignettes, while the last two stand alone. The “novel” is followed by an epilogue — “An Author’s Note to His Readers.” The text is supplemented by black-&-white archival photographs, short explanatory sidebars, and concludes with a glossary of Japanese terms used in the text.

While this description might lead the reader to believe that J-Boys is a textbook — and in some ways it is — it is also a novel deserving of serious attention by adult readers.

Adult readers who live in Japan will find Kazuo’s world of the mid-1960s a valuable key to the mystery of how the Tokyo we know today, with its 24-hour McDonalds, its TV re-runs of Desperate Housewives, The West Wing, and CSI, and its plethora of Starbucks coffee shops, evolved out of the ruins of the old wood and paper city leveled by the firebombs of World War II. And adult readers who’ve never been to Japan will find a sophisticated ethnological and sociological study hidden behind the façade of innocence the schoolboy characters present.

Oketani’s skill — and that of translator Udagawa — is evident in the understated irony of the adult narrator’s account of the 9-year-old Kazuo’s view of the world. This irony makes it possible to discuss such serious topics as the death of a child during an air raid, the prejudice against resident Koreans, and a scandal that arose over the mislabeling of meat, without the judgmental opinions that adults would inevitably offer.

To a group of elementary school boys, old enough to comprehend superficial reality and to feel basic emotion, yet young enough to — like Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby — reserve judgment, all things are as they seem and readers are left to interpret them in ways appropriate to their own ages and levels of experience.

A good example of this is the story “What Wimpy Ate” in the December chapter. After watching many episodes of Popeye the Sailor on TV, Kazuo becomes obsessed with eating a hamburger, just like Wimpy the fat man in the cartoon. The story is told from the point of view of a child, and when Kazuo’s grandmother takes the boys to a Ginza restaurant, hamburgers are all that’s on Kazuo’s mind. The estranged grandfather suddenly appears at the restaurant, and along with him, come classism, arranged marriages, ostracism, family feuds and also the emergence of democratic thinking. Oketani cleverly keeps them from deterring Kazuo, as well as the reader, from focusing on the really important issue — hamburgers.

J-Boys is unusual in that different readers can approach it in different ways, and regardless of their approach, derive from it equal satisfaction. The side-bars and glossary, rather than being a distraction, can enhance the appreciation of the story for young readers or adults with no experience of Japan. For adult readers who live or have lived in Tokyo, the photos provided by Shinagawa Ward are a welcome addition to the text — a historical record of a city in transition between its feudal past and its futuristic present.