Call me Okaasan by Suzanne Kamata: Adventures in Multicultural Mothering. Deadwood, Oregon: Wyatt-Mackenzie Publishing, 208 pp., $16.00 (paper).

[C]all Me Okaasan is the title of Suzanne Kamata’s collection of essays by twenty mothers raising multicultural children, mostly abroad, in a variety of situations.

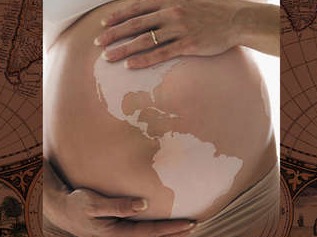

The cover shows a mom-to-be with a map of the world temporarily tattooed on her very pregnant belly. The photo is faceless, so we don’t know if she is smiling with anticipatory joy or cringing with worry as she acknowledges that it’s too late to turn back on the journey upon which she’s embarked. But by the look of her hands, securely cradling the baby, we know she has a grip on the future.

Parenting is universal, and so are many of the unforeseen challenges that face mothers. Having said that, however, many of the mothers in Kamata’s book are in extreme situations. In “Dr. Bucket in Bishikek” (Kyrgyzstan), for example, the mom learns to follow her own instincts during pregnancy and to listen to her own voice in the midst of dirt, a foreign language and confusion. In “Carrying On” (South Africa), the mom picks up her two-year-old, kisses his cheek and makes sure his feet are warm while reading the local news about a violent uprising. She reminds us of mothers everywhere as she tries to carry on “despite politics and worry and irritation and self,” (even as she realizes that the local moms bear a much greater load than she does). In “Mothering Across Cultures” a mother explains things to her English/Iranian son, raised in Japan, who has trouble accepting his family’s “need to do things differently from the mainstream.” This theme is echoed in “A Santa Snafu” (Turkey) where a mom celebrates Christmas in a Muslim country, though this time the mother explains things not just to her child, but also to the Muslim moms around her.

The children Kamata and the other mothers write about often find themselves in difficult situations because of choices their parents have made. In “Eleven Snapshots for Your Baby Book, Reconstructed in Blues” (Austria) we wonder how much the pain and sadness a mother feels at being abroad ends up being borne by the children she raises and by future generations.

And then there’s the foreign language issue. Which language should be used at home and by which parent? In “Promises to Myself” (Israel), the writer could not, when growing up, understand her parents’ Hungarian and vows, therefore, that her own kids will first use all English at home, and only later Hebrew outside. Her children will become bilingual and she will have avoided her parents’ mistake of raising her as a monolingual. In “I am Mutti” (USA) the mom chooses German at home in Seattle because the kids will get English outside at school. Her German husband could not be more pleased. In “Two Versions of Immersion” (Japan) English is used at home and Japanese at school. Each child in the family copes differently with foreign language acquisition and also with bullying.

Another issue that we cannot see when we page through an international family’s photo album is how children feel about their own identities. This book will be helpful to mothers guiding their children through such difficulties.

In three essays, international adoption has an acute affect on the child’s acceptance of self. In “Mothering My Russian Speaking Kids,” the mom teaches them that “diversity is good and that they should be proud.” In all the essays we see mothers like her, instilling confidence in their international kids, and making the extra effort to reassure them of their love and support. Such love and support, it becomes clear, is essential for children to get through and benefit from a multicultural upbringing. Suspiciously, though, the father’s role in that is seldom mentioned.

Kamata has pulled together a collection of stories that will help moms, regardless of where we are living and who we are raising, navigate through sometimes rough waters with humor, patience, curiosity, and confidence. Kamata and her writers show their kids, by example, the strength necessary to survive and thrive during their multicultural childhoods.

The essays that Kamata gathers offer a wide perspective, much richer than the warble of one writer droning on about the child raising challenges of a single country. That the problems the writers address are not limited to one country, or even a single region, assures that this is an important book. The tales it contains will likely inspire readers (presumably expatriate parents) to share their own travails, and the index and contact information with which the book closes invites readers to do just that. In such sharing, there is strength.