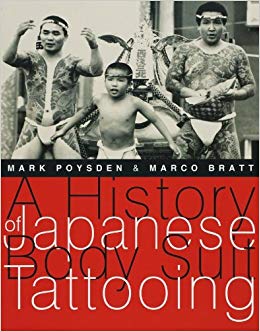

A History of Japanese Body Suit Tattooing, Mark Poysden & Marco Bratt, KIT Publishers,

Amsterdam, 2006, 224 pp.

[W]HAT COULD have been yet another among a disappointingly un-distinguished succession of books about the art, craft, and culture of body art is in fact refreshingly good. Mark Poysden and Marco Bratt’s subject is the traditional Japanese body suit tattoo, and like their subject, A History of Japanese Body Suit Tattooing covers a lot of ground.

Traditional Japanese tattooing is one of Japan’s high arts and is widely recognized by the rest of the world as the pinnacle of the craft, though its virtues are widely denied in its native land. The very early history of tattoo in Japan is vague, though it is certain that before the Edo period, during which the art reached maturity, relatively small tattoos identified criminals, inveighed religious piety, and were assumed as indelible pledges of love. During the Edo period, the full body tattoo evolved concurrently with ukiyo-e, the popular woodblock print. Some of the great masters of ukiyo-e were also tattoo designers and their iconographies and sense of style survive in the creations of today’s traditional tattoo artisans.

As it rapidly developed, the body suit tattoo was embraced by Japanese workmen, largely in imitation of the outlaw heroes of the 14th-century Chinese novel, Shuihu zhuan (in Japanese, Suikoden), which enjoyed marked popularity in Japan. In a more complex (and related) way, it was also embraced by gangs and politically conservative elements, culminating in the yakuza, the Japanese criminal underworld (a focus of this book). Traditional tattoo’s associations with the working class on the one hand, and with the criminal underworld on the other, are primarily responsible for the horror most middle and upper-class Japanese feel when confronted by it.

A History of Japanese Body Suit Tattooing comprehensively reviews the larger cultural context within which the art of the traditional Japanese tattoo arose. Historically, it migrates from the early Jõmon through the present day, perching on such interwoven culturally iconic Japanese phenomena as bushidõ, class divisions, the floating world, kabuki, fire fighters, ukiyo-e, and the yakuza. It discusses in gratifying depth tattoo’s evolving tradition, technique, and motifs. And it touches, presciently and poignantly, on the future of traditional tattoo in Japan. The book is profusely illustrated. The only thing it seemingly doesn’t do (and this comes as a surprise, since one of its authors, Marco Bratt, is himself a tattooist) is to address the existential aspects of the art, so central to its mystique: what is it like to receive and bear a traditional tattoo? One can’t really fault the authors, though, since the secret world of traditional Japanese tattoo is, for obvious reasons, rather exclusive.

Finally, and regrettably, I would be remiss if I didn’t point out the book’s simple, and for most readers negligible, shortcomings. Structurally, it is a bit uneven and occasionally redundant, and while it was clearly exhaustively researched, I (for one) can’t employ it as an authoritative source because it isn’t annotated. Nevertheless, for anyone serious about or even just casually interested in traditional Japanese tattoo, this book is a must-read, a must-have. It is colorful, at times exotic, and rewardingly complex. It is, in these ways, just like traditional Japanese body suit tattoo.