A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a selective guide to DVDs and videos,

A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a selective guide to DVDs and videos,

Donald Richie, Kodansha, 300pp

[A]s Donald Richie tells us, at the end of the nineteenth century, a cameraman from the Tokyo Mitsukoshi Department Store shot some of the first film footage in Japan, and thirty-odd years later, Japan was the world’s largest film producer. But by the 1960s, the industry was in decline and the major studios began to diversify into supermarkets, baseballs teams and railways. Today, a good number of Japanese films are made with the expectation that profits will come not from ticket sales but from video rentals and television rights.

A Hundred Years of Japanese Film may be Richie’s last word on the subject, yet it shows no valedictorian airs. It is, as ever with Richie, informative and engaging, and notable also for its sly wit and insight. Thus Ishihara Shintaro, whose novel was the basis for Punishment Room (1956), is described as ‘later a right-wing politician and, however improbably, the governor of Tokyo,’ while Twenty-Four Eyes (1954) is a film ‘so undemanding of emotion and yet so skillful in obtaining it that audiences all over the world have been reduced to (or ennobled by) tears.’

Richie’s premise, a ‘generalization…largely true,’ is that Japanese film is ‘presentational,’ in contrast to Western film, which is ‘representational.’ The latter assumes a reality; the former offers a version, and this leads to the eclectic vigor of Japanese culture. Not having originated the form, the Japanese were able to make a cinema that combined the given with the taken. Further, film gave Japan ‘a new way of looking at the world.’

The initial part of the book, dealing with the establishment of the first studios and the separation into genres, is scholarly and exhaustive, and suggests, perhaps, a readership of film students. Here, as elsewhere, Richie balances technical analysis, studio politics and cultural comment. No better account is likely to be found.

A good number of the prewar directors are doubtless new to general readers, and of these none seems more worthwhile seeking out than Yamanaka Sadao. Richie devotes six pages of tightly argued discussion to his work, of which only three films survive. Yamanaka was both a contemporary and close friend of Ozu, though he differed in being a director of jidaigeki — or ‘gendaigeki with topknots.’ Richie: ‘Japan has a category for everything.’

World War Two brought censorship; the subsequent American Occupation more of the same and the burning of films. The Americans left mainland Japan in 1952, but before then Japanese directors had turned to making films that depicted the realities of postwar Japan, and ‘all Japanese cinema became, for a season, shomingeki.’

After that season ended, Japanese cinema returned to juggling genres, and while Ozu and Mizoguchi continued to be popular at home, the success of Kurosawa’s film Rashomon at the 1951 Venice Film Festival brought Japanese cinema on to the world stage. In Japan, however, Kurosawa’s new-found international fame led to criticism. How could he be a Japanese director if foreigners were able to understand him? Richie has much of value to say about such seeming contradictions, and his conclusion is typically provoking and judicious: today ‘the Japanese have reached the point where they have ceased to be so acutely aware of the distinction between what is Japanese and what is foreign.’

Were the 1950s — the time of Tokyo Story, Throne of Blood and Sansho the Bailiff, to name but three — a golden age? Richie throughout shows remarkable restraint; indeed, a criticism of this work may be its lack of outright condemnation. One misses the Richie who said ‘there is always more junk than worth in this world.’ Against that may be set his pronouncement ‘that the joys of comprehension are the only true joys there are’ — both in an interview in this journal with Janet Pocorobba.

The Japanese film industry suffered, like its Western counterparts, from the advent of television. Between 1960 and 2000, film production went down by nearly 50 per cent, while the number of cinemas fell by two-thirds. This led to more independent productions and the creation of a Japanese ‘new wave’ — the politically conscious and ‘foreign-inspired’ experimental films of Oshima, Yoshida and Shimoda.

Richie is careful to distinguish between the Japanese film industry and the Japanese cinema. Financial decline was not always matched by artistic slump. The films of Imamura Shoei and Yanagimachi Mitsuo are testament to this. Nevertheless, as the century reached its close, anime and violent, Tarantino-like films, such as those of Kitano Takeshi and Fukasaku Kinji became both profitable and pervasive. This, too, is the situation today in England, where Kitano is unaccountably revered as a major auteur, and companies like Tartan Asia Extreme and Tokyo Bullet release the majority of contemporary Japanese films.

Despite — or because of — the Western influences, Richie sees a Japanese tradition continuing. ‘What we might call Japanese — neither logical nor casual, but emotional’, evident in Naruse and Mizoguchi, can be found today in the work of Kitano and the like, in their preference for the long shot. And perhaps above all in the films of Kore’eda Hirokazu, the most interesting of the young directors, whose stated aim is to ‘follow in the footsteps and continue in the path of Ozu, Mizoguchi and Naruse.’

A Hundred Years of Japanese Film includes a selective guide to videos and DVDs and a glossary. The text itself is well illustrated, finely constructed and generous. It states quite clearly that there is more to Japanese film than the triumvirate of Ozu, Kurosawa and Mizoguchi. The novice or expert will learn much. Even those with little interest in film will find their understanding of Japan increased; and in that sense it resembles Edward Seidensticker’s Kafu the Scribbler, another work in which a close reading of one aspect of the culture illuminates the whole. Yet readers of all stripes will do well to remember that Richie is above all a writer, one whose ostensible subject just happens to be Japan. Readers of this history are urged to turn, if they have not yet done so, to his novel Kumagai, which must count among the most subtle of autobiographies.

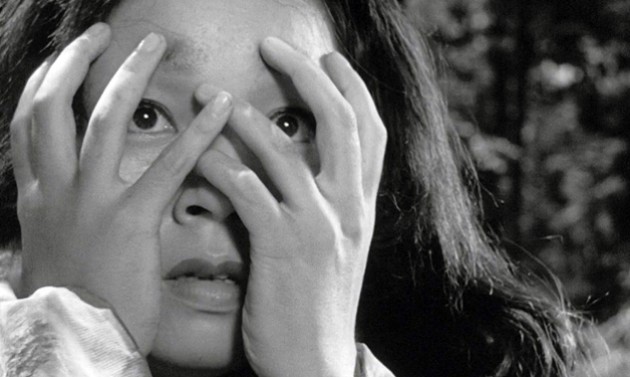

As in the West, the earliest films shown in Japan were accompanied by a narrator — or

‘benshi’. In the words of Donald Kirihara, his job was to ‘reinforce, interpret, counterpoint, and in any case to intercede.’ A better description of Richie would be hard to find.