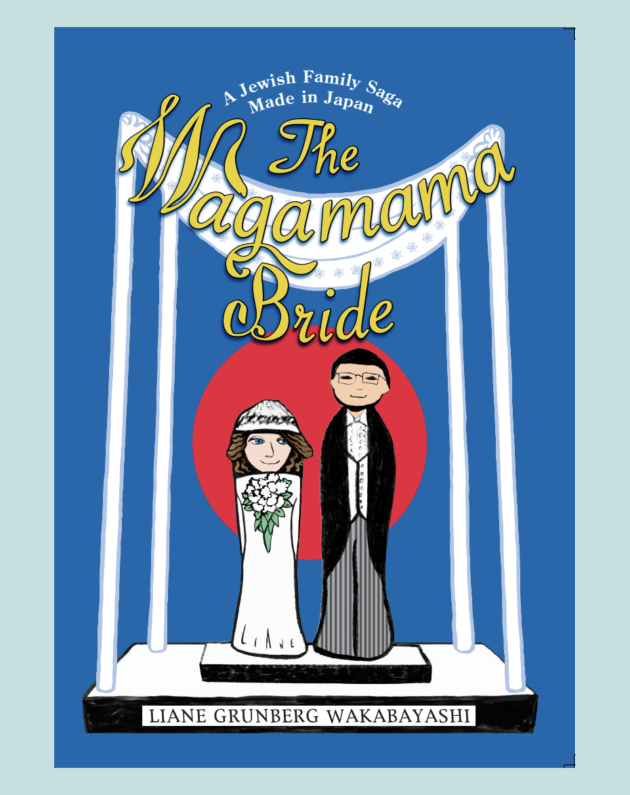

THE WAGAMAMA BRIDE: A Jewish Family Saga Made in Japan by Liane Grunberg Wakabayashi – reviewed by Lora Sharnoff

THE WAGAMAMA BRIDE: A Jewish Family Saga Made in Japan by Liane Grunberg Wakabayashi, Goshen Books of Jerusalem, Miami and Tokyo, 265 p., $16.95.

It has been common for several decades for Westerners in Japan to seek enlightenment and spiritual comfort in Buddhism and other Asian religions. It’s a well-traveled road, but Liane Wakabayashi’s path to spirituality in Japan, as depicted in this book, is unique.

A native New Yorker and a not-strictly-observant conservative Jew, Liane Grunberg (later Wakabayashi) first came to Japan armed with degrees in Art History and Arts Administration, to cover blockbuster art exhibitions held in department stores for a Conde Nast magazine in 1985 and then again in 1987. She lost her return ticket the second time and ended up staying, acquiring a position as a copyeditor for the Japan Times which gave her a platform to write about artists working in Tokyo. Thereafter, Liane had a series of fortuitous encounters. Answering an ad for a secondhand bicycle, she found herself at a traditional style house with a picture perfect Japanese garden carp pond, which turned out to be available for rent, as the couple living there were about to move to Spain.

Next Liane was sent by the Japan Times to Sapporo to cover the annual snow festival, where she was unexpectedly greeted in Hebrew by a member of the Israeli team that, though hailing from a nation hardly known for snowfall, had won the international snow sculpture competition,. While chatting with the friendly Israeli, Liane came up with the idea of holding an exhibition of Israeli artists in Tokyo at the Jewish Community Center. Among the artists she contacted was a French-Israeli woman, who first rejected the proposal but later changed her mind and joined the exhibition. The woman taught Liane the Japanese word “wagamama” (selfish) and introduced her both to shiatsu (acupressure) massage and the White Crane Clinic that specialized in it.

Liane’s saga really takes off when she visits the clinic, whose Incho (clinic chief) looked as if he had “walked out of a feudal samurai household” and his apprentice, who resembled a younger version of this man and introduced himself as “Ichiro, the translation.” The translation began to treat Liane, and also to woo her with his quaint yet comprehensible English, which she decides not to try to correct. During the course of several shiatsu and eventually acupuncture sessions, Liane and Ichiro fall in love despite, or maybe because of, their very different backgrounds. Ichiro had never met a Jew, and Liane told people when she was first leaving for Japan that she would never marry a Japanese man, but marry they did, a couple of times: at a large, fancy Shinto ceremony at the Imperial Hotel and later a much smaller Jewish ritual.

Their marriage takes the couple at various times to the United States and England, and eventually to Israel. The book is full of amusing incidents of culture clash such as Ichiro’s shock when Liane’s maternal grandmother sends back an unacceptable meal at a Wimbledon restaurant—something a Japanese woman would be highly unlikely to do—or when Liane brings white chrysanthemums to her in-laws, unaware that those flowers are generally associated with funerals. However, the book also contains some very touching stories such as those concerned with Liane’s daughter’s mental health problems.

Along the way, Liane begins to delve more into her Jewish heritage while living with a man who embraces Taoism, Buddhism and various Asian traditions. She starts spending more time at the Jewish Community Center and then at the first Chabad houses in Tokyo, which welcome all Jews, regardless of their background and level of observance. Ultimately she senses Israel beckoning so takes her son and daughter with her to live there. The book closes with a depiction of her more recent life in Jerusalem with her Asian-looking Jewish children.

The author is diligent about providing English equivalents for all Japanese, Hebrew, and Yiddish words she uses. My one quibble is that she informs us she wore a “Yumi Katsura designer gown” for her formal wedding, without explaining how prestigious this is in Japan. Although Yumi Katsura is a designer of considerable standing in her native land, she is not well known internationally. However, this is a very minor complaint about an otherwise well-written, witty and moving book.

When I was living in New York City, I occasionally saw advertisements with photos of people of different ethnicities holding bread with the catch phrase, “You don’t have to be Jewish to love Levy’s: real Jewish rye.” In the same way, I feel that you don’t have to be Jewish (I am not) to enjoy and learn something from The Wagamama Bride.