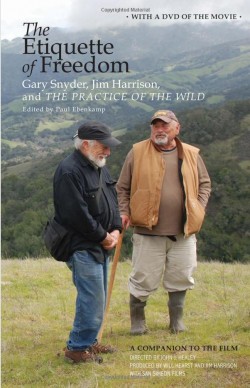

The Etiquette of Freedom and The Practice of the Wild (a DVD film) by Gary Snyder and Jim Harrison. Edited by Paul Ebenkamp; Counterpoint Press, 2010. 131 pages.

[T]he conversation between poets Gary Snyder and Jim Harrison in the book The Etiquette of Freedom, based on several days spent together while walking over the hills of southern coastal California, is a rare meeting of minds and personalities. A DVD film, The Practice of the Wild, co-produced by Will Hearst and Harrison, accompanies the book, which also contains a generous selection of poems that illustrate Snyder’s ideas. What we have here is a treasure: a rambling conversation between two of America’s most original poets –– clear-eyed, unsentimental outsiders, both outdoorsmen who have spent their life probing the nature of nature.

In Asian terms, Snyder, 80, is the host of the book and film, and Harrison, 73, is the guest. A lifelong fan of Snyder’s work, Harrison assumes a dual role of interviewer — drawing Snyder out, opening up themes, offering him a stage to hold forth, which he does in his usual sharp, light and clear way. We know this encounter is the real thing when Harrison tosses out one of his favorite quotes of D. H. Lawrence that he frequently uses on his own interlocutors: “The only aristocracy is that of consciousness.” It’s easily passed over, but Snyder bites into the moment and their two minds engage:

GS: What do you think he meant by that?

JH: I think he meant that the person who is most conscious lives the most intensely –– if “intensity” is the real pecking order, since life is so limited in length, as we are both aware of vividly––

GS: The most vividly. I’m not sure I agree with how he meant that, but that’s a good question.

JH: Why do you disagree?

GS: Oh, because it’s too spectacular, too romantic.

JH: Well, so was he.

GS: Of course. At any rate, you could set that beside an East Asian idea of the aristocracy of consciousness, and a Chinese or Korean idea of that would be much calmer, much cooler. Not like a hard glowing gem-like flame, not like a flaming candle burning out––

JH: That’s what Kobun Chino Sensei said; they criticized his friend Deshimaru because he said, “You must pay attention as if you had a fire burning in your hair.” And Kobun said, “You must pay attention as if you were drawing a glass of water.

GS: Oh, that’s better.

JH: The concept of the divine ordinary.

The title, The Etiquette of Freedom, comes from one of Snyder’s early seminal essays, at the heart of The Practice of the Wild (1990), which explores his ideas behind the terms Nature, the Wild and Wilderness. In their fullness, the three terms are meant to encompass all aspects of phenomenal life, the whole of creation, a process in which humans are one part (though vastly threatening to the other parts). He wrote: “The lessons we learn from the wild become the etiquette of freedom [for humans].” Approaching Nature from the largest perspective, says Snyder, has sometimes caused him to be misunderstood.

GS: People, including environmentalists, have not taken well to the distinctions I tried to make between Nature, the wild and wilderness. You know, I want to say again, the way I want to use the word “Nature” would mean the whole universe.

JH: Truly.

GS: Yes, like in physics.

JH: Right, exactly.

GS: So not the outdoors.

JH: No. That’s a false dichotomy.

GS: Yes.

JH: –or a dualism.

GS: Yes, Nature is what we’re in.

The term “wild,” as used by Snyder, is a metaphor for the natural processes within Nature when least affected by man’s disproportionately heavy hand (but even our destructive, consumptive role is part of the natural process, as Nature, in the broadest sense, is constantly engaged in a vastly complicated destruction, consumption and renewal). Fully understanding these terms is conjoined by the role of time as measured in hundreds of thousands and millions of years and not at the rate of humankind’s anthropocentric perspective. For more on these terms, see The Practice of the Wild, where he wrote, “Nature is not a place to visit, it is home,” and, in a prophetic stroke: “It is the present time, the 12,000 or so years since the ice age and the 12,000 thousand or so years yet to come, that is our territory. We will be judged or judge ourselves by how we have lived with each other and the world during these two decamillennia.”

For more on his ideas on bioregionalism and environmental issues, see Turtle Island (1974), his homage to North America, and his other essay collections and talks: The Real Work (1980), A Place in Space (1995) and Back on the Fire (2007). All of Snyder’s essays are gems. Those on Buddhist themes are filled with poetic prose rising to the level of inspired teishos.

The title, The Etiquette of Freedom, functions as a loaded metaphor, speaking of the importance of living in Nature with a humbleness that reflects humans’ disproportionate role—and responsibility—within the natural processes of creation and life and death. Etiquette means to show respect to a person or occasion. We see this attitude reflected worldwide in ancient cultures when someone asks for understanding before taking a creature’s life or before felling a tree for a home. By exercising an “etiquette” relationship with Nature, we can realign our sense of place and in turn, we experience a greater correctness in a more responsible relationship with Nature. Snyder himself has come to personify a meme which evolved out of the counterculture movement and has been absorbed into mainstream culture: the way to a richer life is to settle in, to reinhabit a rural area, to learn the names of the plants and animals, the geology, the history of the indigenous people, to study the folklore, to engage in civic life, to pay attention to the schools, to deepen one’s sense of self, to live life fully as a thoughtful member of a bioregion in which one strives to play a grateful and productive role. It is a meme for a practical, reality-based approach to life, and one which he played a major role in creating.

The interplay between the individual and Nature has been Snyder’s subject since his first translations of Cold Mountain (Han-shan) poems as a student at Berkeley. For more than 50 years, he has been the American poet who has most fully embraced the subject of Nature, and the nature of consciousness. In 1955, he left America for Japan to study Zen. His public life began, in a way, as a fictional character in the novel Dharma Bums (1958), in which Jack Kerouac created a charismatic, heroic character named Japhy Ryder (Gary Snyder)—a young, self-assured American poet and outdoors man. In the late-60s, when he returned from Japan to live in America again, he immediately became a central figure in the evolving counterculture.

His influence was based on his poetry and his practical ideas of returning to the land, which were embraced as a rallying cry by many young people, and canny elders. His approach was an extension of Emerson’s and Thoreau’s ideas on self-reliance and nature, and Buddhist philosophy. Wary of becoming a counterculture spokesperson, he quickly retreated to live in the isolated Sierra foothills near Nevada City, where he worked on his craft. After Turtle Island, he assumed a role of poet and environmental social critic. In his late period, he taught at the University of California at Davis, while continuing to publish poems and essays. Since then, the mythology surrounding him as a teacher has deepened. Over the coming decades, his work will continue to travel well beyond America’s shores, and one feels the mythology surrounding him has only just begun.

Snyder’s work has always been aligned with his commitment to Zen. Looking back now, his poetry and essays fan out like one long scroll of his life, a record of what he’s seen and felt and learned. To throw him together here with Jim Harrison’s Ikkyu-like spirit is a gift — two American poets who have extended the lineage of Emerson and Thoreau (Dogen and Han-shan) — two old men, well-worn and free, walking and talking, and turning the wheel.

Roy Hamric writes frequently about poets and Asian literature. See his interview with Jim Harrison in Rendering the Lightning, KJ No. 73, Fall 2009.