Kyoto View 86: Kyoto Dwelling: A Year of Brief Poems, by Edith Shiffert – reviewed by Margaret Chula, from KJ 7 (Summer 1988)

KYOTO DWELLING: A YEAR OF BRIEF POEMS

by Edith Shiffert, Charles E. Tuttle Company 1987, 115 pages

The poet Edith Schiffert resided in Kyoto from 1963 until her death, at the age of 101 in 2017. Her poems appeared often in KJ over the years. This review of her classic Kyoto Dwelling, from KJ7, Summer 1988, is by long-time KJ associate (and poet) Margaret Chula.

“Since I came to Kyoto in 1963, much has changed, but even more has not changed. They are the things written about here, at the moments when they were experienced.”

In Kyoto Dwelling the author takes us at her own pace month by month through one year. As we move through the seasons, it soon becomes evident that these poems are not about the many dwellings that she has lived in. They are about the state of dwelling: being and noticing.

A temple garden—

green blades pulled up from the sand

wither in small heaps.

And before we have turned many pages, our rhythm has slowed to where we too can pause and notice the blades of grass drying and yellowing. Or feel the warm comfort of quilts that have been aired in February sunshine.

Edith’s poems are about nature. She believes that “to participate in natural events lets one be briefly timeless and universal.” Whether walking up a mountain path or along city streets, she has a poet’s eye and an uncanny skill for isolating a moment in nature and transforming it into a poem about awareness.

Eternally washed,

pebbles in the narrow stream

of clean snow water.

In her daily life as she watches the sun set between bamboo, tortoises playing in the emperor’s pond or

Inside the plum grove

only one tree with blossoms.

Blue, blue winter sky!

She has a child’s delight but also an adult’s ability to transmit that delight in a poem. It is with this same lively expression that she writes about “the happy old man,” Minoru Sawano, to whom the book is dedicated. Natural as a heron, he blends into the landscape of her poems — gliding down the pathway, leaping in the air while feeding pigeons or

That noble old man,

my husband, he is laughing.

Birds sing, and dogs bark!

Much of the enjoyment for those of us who live in Kyoto is following her to familiar places. Whether it be climbing Mt. Hiei, strolling along the Kamo River or

Sitting for an hour

by the tea hut without tea.

Basho and Buson!

Reading these poems leaves us with a new sharpness of vision. And yet, most of them could just as easily be about any place, any time and the viewer could be anybody. For the poems in Kyoto Dwelling are about insights, seeing from within, and are not subject to the constraints of time or place. As the author says in her introduction: “There is the Kyoto that is nowhere in particular. A Taoist realm, a place of imagined satori, somewhere like anywhere in America or Europe or Asia in any century.”

Underlying all of Edith’s poetry is a feeling of detachment and compassionate understanding. Her years of Buddhist study and training have culminated in a life of observing nature from a calm center, whence her poems bloom.

The one lotus bud

on the pond, not yet open

does not know it waits.

More than 350 poems! Yet I read Kyoto Dwelling at one sitting. Although all the poems are written in three lines and follow the traditional 5-7-5 haiku form, the author prefers to call them “brief poems.” Edith has been writing in this style for fifty years and does so gracefully. While written in a similar form, each poem is unique in its content and mood—moods which vary from contentment to loneliness to humor. Anyone who’s lived in a small house knows the frustration of

Four electric cords

tangled on a chair rocker.

Kyoto in winter.

Moods are further accentuated through contrast of sounds. The “quietness of snow” in one poem is punctuated by “the barking dog” in another and “voices of crickets” are contrasted to the “yawns, laughs, belches, coughs” of the splendid old man.

A lovely complement to the poems are sumi-e paintings by Koka Saito which introduce each month. Mr. Saito is a naturalist, familiar with the birds and flowers that he paints. With skillful brushstrokes, he has mirrored Edith’s poetic images with soft beauty and affection.

Kyoto Dwelling is a book to savor, to share, to pick up when you need to slow down. It is a reminder of that other life we experienced as a child, a life full of wonder and awe—the life of a woman poet in her seventies.

To live a long life

we work at doing little

and look at the trees.

Edith was interviewed in the first issue of KJ (1987), and profiled by Jane Wieman in KJ 70 (2008). Her more recent books of poetry include When At the Edge, In the Ninth Decade, and Pathways (a selection spanning six decades, published by White Pine Press). Her poems are also featured in The Forest Within the Gate, by John Einarsen. (New York Times obituary, here).

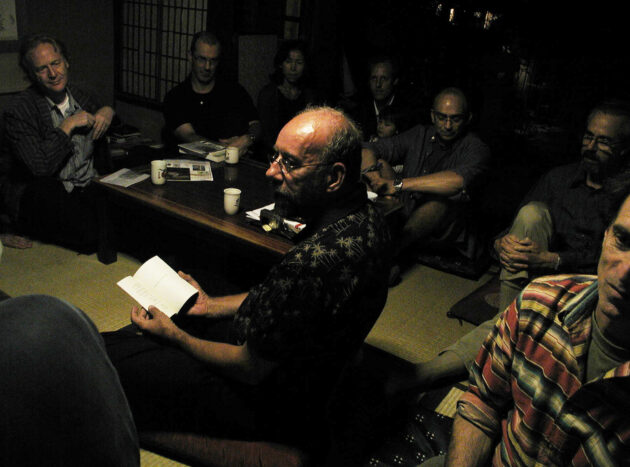

KJ held a reading by Edith and Dennis Maloney of White Pine Press, September 22, 2006, at Sherry and Hirofumi Nakanishi’s Nama Chocolate Organic Teahouse in Okazaki — a very memorable gathering of local friends of Edith and KJ.

Margaret Chula lived in Japan for twelve years where she taught English and creative writing at Kyoto Seika University and Doshisha Women’s College. Her twelve books include Grinding my ink and Shadow Lines, which received Haiku Society of America Book Awards and One Leaf Detaches, recipient of a Touchstone Distinguished Book Award. Her most recent collection, Firefly Lanterns: Twelve Years in Kyoto is a memoir written in haibun form. She has been a featured speaker at writers’ conferences throughout the United States, as well as in Poland, Canada, Peru, and Japan. Serving as president of the Tanka Society of America and as Poet Laureate for Friends of Chamber Music, she is currently on the advisory board for the Center for Japanese Studies.

Photos by Ken Rodgers