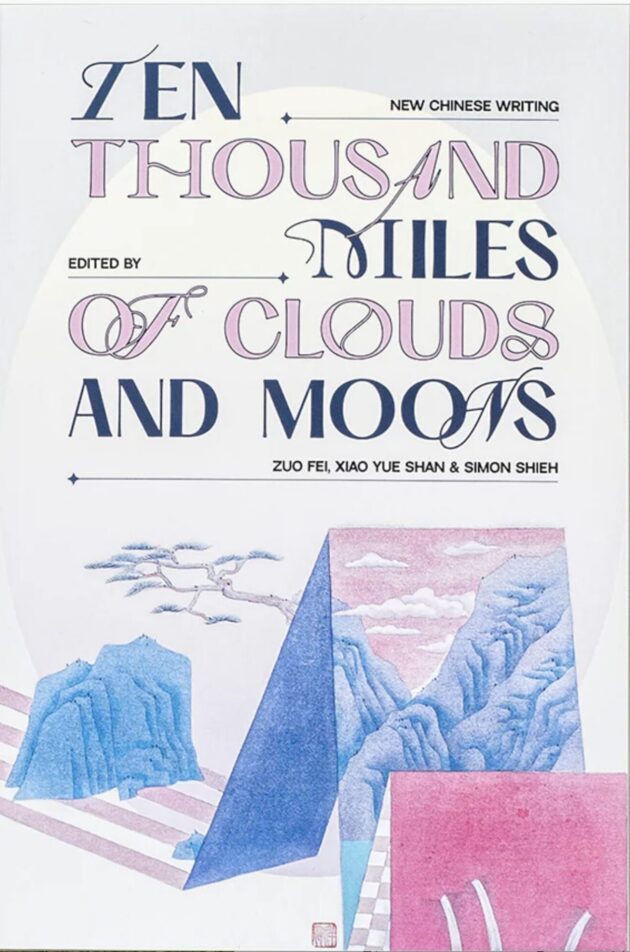

Ten Thousand Miles of Clouds and Moon: New Chinese Writing edited by Zuo Fei, Xiao Yue Shan, and Simon Shieh. UK: Honford Star, 280 pp., ¥3324 (paper).

In Qian Zhongshu’s famous 1947 novel Fortress Beseiged there is a scene in which one of the characters, a writer and intellectual, writes to another: ‘I just wish I could invent a fresh and fleeting expression that only I could say and only you could hear. […] I’m so sorry that to you who are without equal in the whole world, I can only use cliches which have been worked to death for thousands of years to express my feelings.’ This is a picture and an expression of the great burden of the past carried by Chinese writers, who are always conscious of the vast tradition of Chinese literature that stretches behind them, hampering efforts to find new ways of expression, new themes, new images. What’s especially interesting about Ten Thousand Miles of Clouds and Moons, a splendid anthology of new writing from China published by the Beijing-based literary magazine Spittoon, is the different ways these young award-winning writers come to terms with the literary tradition and how that past informs their work.

Chen Chuncheng’s story, for example, Mass in ‘Dream of the Red Chamber’ is a witty blend of sci-fi and parahistory which has much in common with Vladimir Sorokin’s Blue Lard. Here, China’s greatest literary masterpiece Dream of the Red Chamber has slowly vanished from the record, and the global government and a terrorist organisation are both attempting to piece it back together from fragments that appear in the most obscure and magical places, like the bottom of the Mariana Trench. The hero of the piece is kidnapped by anarchists who see the work as a bible and want him to try to piece together his memories of the text. A key question for all involved is: ‘What is the main idea of the Dream of the Red Chamber?’ because answering this question will yield the secret of the universe itself. Although ostensibly about Dream of the Red Chamber, in the metaphysical background of the story is the Yi Jing, which sees the transformations of the world as a giant text, a book of changes that must be deciphered.

Da Tou Ma’s story of disaffected, unemployed Beijing youth, the lie-flat tan ping 躺平generation, A Catcher in the Rye, is a fine piece of skat, as the title signals. Here, the famous final gatha of the Diamond Sutra bursts into the text like an explosion, causing the anger of the narrator to dissipate. However, rather than offering any redemption, it serves instead to amplify the narrator’s nihilism.

Lady Wei’s Dream by San San is a story that could have come straight out of Pu Songling’s Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio. In Stellar Corona by Huo Xiangjie, an allegorical history of China, new forms of knowing are framed by reference to the past, not by naming, but by renaming: ‘We rename the aspects that had once escaped our notice, thus forming new systems of knowledge.’ Here the new is constantly in danger of being subsumed by the old. Hei Tao, in an essay, represents this interaction of the old and the new in contemporary Chinese literature in the beautiful image of a Ming Dynasty magnolia whose trunk is withered and dead but which nonetheless manages to put forth a cloud of blossom.

Jiang Li’s poem ‘Miniature Landscape’ describes a miniature landscape with a bonsai tree, those little pots containing a slice of nature reduced in size which are ‘an accessory to leisure’ in Chinese life: ‘disheartened intellectuals seek solace in retreat — landscapes/gardens, poetry, and paintings,/all constitute a bitter prelude towards nature’ in a yearning for retirement to a rustic retreat that has been the dream of Chinese intellectuals and a prominent theme in their poetry since the time of the famous Six Dynasties poet Tao Yuanming. Here those aspirations have shrunk and been accessorized. Fu Wei’s poem ‘Lines on Ripped Silk’ has an epigraph of two lines from the late Tang Dynasty poet Li Shangyin, which Fu Wei develops into a meditation on loneliness and regret, interacting with his predecessor in the way Chinese writers have been doing for thousands of years.

There is a wealth of different kinds of writing here: fiction, poetry, personal reminiscences, and non-fictional essays (Hei Tao’s are especially noteworthy). There are potted biographies of the writers and the awards they have won, and, what’s especially good to see, potted biographies of the translators too. It’s encouraging to see the work of the translators given as much prominence as the work of the writers themselves because, without the excellent efforts of the translators, none of this material would be available to English readers. This anthology shows that young Chinese literary culture is vibrant, multifarious and exciting. Let’s hope that big Western publishers take note and commit to making some of this work more widely available to English reading audiences.

—Quentin Brand