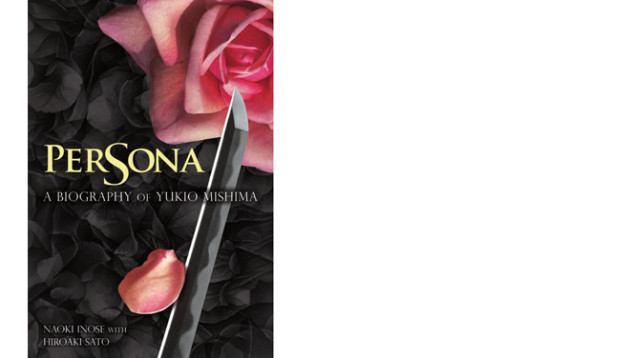

Persona: A Biography of Yukio Mishima

by Naoki Inose with Hiroaki Sato. Stonebridge Press. 2012.

xii and 852 pp.

[H]iroaki Sato’s preface suggests that, with the help of acknowledged assistants, he has added considerable substance to the English version of Naoki Inose’s original Japanese biography of Yukio Mishima (1925-1970). For brevity’s sake, I’ll refer to Inose and Sato as “the biographers.”

Persona is like a flashcard pastiche, much of it based on interviews and private correspondence fused with the historical events through which Mishima moved. Mishima’s lifelong obsession with death and suicide and his sensational death by seppuku at forty-five, haunts the biography.

The following is a small sampling of the fascinating details permeating Persona. Born Kimitaka Hiraoka, Mishima was sequestered from his family by his paternal grandmother, Natsuo, a descendant of a daimyo. She was a widow, a rich commoner who gave him her version of an elite aristocratic upbringing. Kimitaka was not allowed to play sports or mingle with other boys. He was given dolls as toys and girls as companions.

Mishima grew up loving ancient Japanese literature, particularly the Kabuki Theater, for which (he later wrote modern Kabuki drama) and European literature. He was physically thin and weak, obedient, polite, shy and yet affable. He scribbled prolifically. When Natsuo died Mishima became obsessively close to his mother.

His father thought writing was unmanly and destroyed any of his son’s creative efforts he found. His mother endeavored to save them. Until he died, Mishima would show nearly all his manuscripts to his mother first.

![By Shirou Aoyama [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.kyotojournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Yukio_Mishima_cropped.jpg)

Obedient to his father’s wishes, Mishima entered Tokyo Imperial University’s law, rather than literature, faculty. He worked briefly in the Finance ministry. After he quit, his father finally blessed Mishima’s desire to write, stipulating he had to be “the best.” Mishima quickly become a popular writer and celebrity, who, among other things, acted in films and made one.

Confessions of a Mask (1948), written from a homosexual man’s viewpoint, raised questions about Mishima’s sexual orientation. The biographers are cautious here. The biography notes that Mishima liked gay bars, and includes his remarks about “boy love,” but counters this with his family’s insistence on his heterosexuality.

The biography positively identifies only one person he slept with prior to his marriage: Sadako Toyoda, a rich restaurant owner’s daughter. He was with her when he telephoned a friend at 1:30 a.m. to proclaim that he had finally sexually satisfied a woman.

In 1955 Mishima took up bodybuilding. This put muscles on his slender body, yet he remained clumsy at sports. He was hopeless at boxing and got promotions (dan) in kendo for “spirit” rather than ability. This may have been thanks to his fame.

About this time Mishima emerged as an active right-wing fanatic. He was bitter about Emperor Hirohito renouncing his divinity—more angry with the man than the Occupation. He became obsessed with failed patriotic rebellions from the past, most notably the young officers revolt on February 26, 1937. His most famous short story, “Patriotism” (Yūkoku), is about a rebel officer and his wife committing seppuku after the failure of the 2/26 Incident to create an emperor (tenno)-centered utopia. To bring about a tenno-centric warrior state, and to fight Communist revolution, Mishima created the paramilitary Shield Society. Mishima convinced the head of the Ground Self-Defense Forces, Yasuhiro Nakasone, to let his society practice on GSDF grounds. (Nakasone privately compared the Shield Society to a theatrical group, the biography notes.) Mishima trained with the GSDF. On November 25, 1970 Mishima and Shield Society cohorts attempted a coup d’état by taking over Tokyo’s Ichigaya Camp, the headquarters of the Eastern Command of Japan’s Self-Defense Forces. They bound and gagged General Mashita and Mishima inveigled the troops outside to join his patriotic rebellion. They jeered him. Consequently Mishima committed seppuku. But not because he was ridiculed.

The biography discloses that Mishima knew the coup would fail and that he would commit seppuku and details how Mishima planned for his eventual suicide long in advance. Even so, the seppuku did not go completely as planned. The man who was supposed to decapitate Mishima muffed it and someone else had to do it. Yet the biographers write: “It was a magnificent seppuku.” Whoever cleaned up the mess probably had other ideas.

Persona is well researched and contains much tantalizing insider information. Like a good novel, it leaves more questions than answers about the man behind the persona. Foremost among them is why Mishima chose to die in the prime of his personal and professional life.