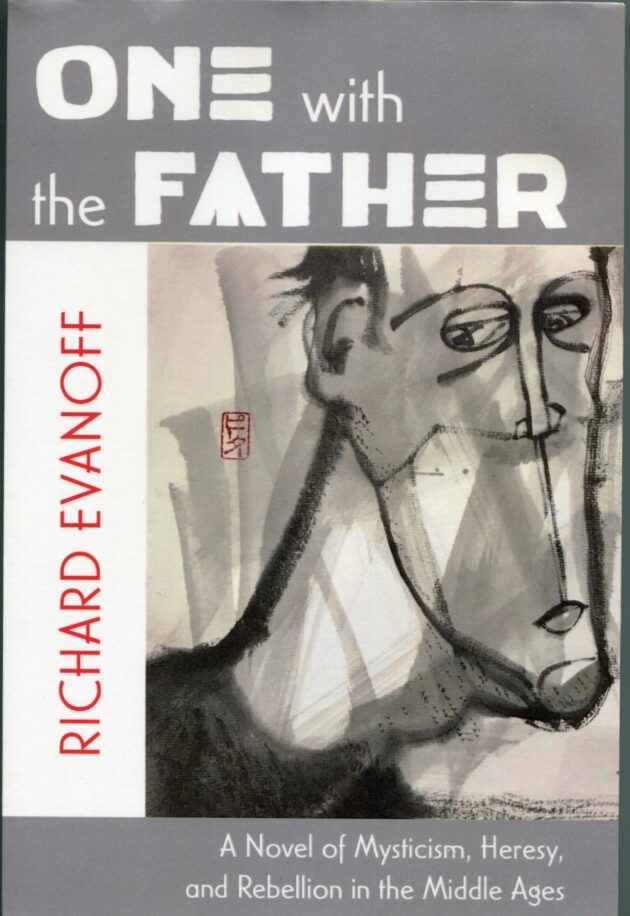

One With the Father

—A Novel of Mysticism, Heresy and Rebellion in the Middle Ages

Richard Evanoff, Resource Publications, Eugene, Oregon 455pp

“A saint is simply someone who has succeeded in becoming the ordinary person God intends us all to be. The rest of us are still trying to figure that out, so it’s we who are extraordinary.”

For some, the Covid lockdown was an incarceration. Others hunkered down and found it liberating. Projects that had been relegated to the back burner by the everyday distractions of “normal” life caught fire, fueled by more focused attention spans. One such long-neglected endeavor was a novel first envisaged by Tokyo-based poet, writer, editor and publisher Richard Evanoff some 45 years previously. Ostensibly the resultant 445-page book (“written in reply to Dostoyevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov and Tolstoy’s The Kingdom of God is Within You”) deals with a Christian rebel in theocratic 14th century England, but the author’s long familiarity with Japan and Asia draws interesting and indisputable parallels with Eastern theological tropes. Territory touched on for example by D.T. Suzuki’s essays on ‘Meister Eckhart and Buddhism,’ or ‘Crucifixion and Enlightenment,’ in Mysticism Christian & Buddhist.

Essentially, the basis of the tale is a retelling of the familiar parable of a favored son deliberately sheltered by an ambitious father from the harsh realities of existence, who inevitably breaks free, renounces his privileged upbringing, and sets out to find the Truth. Think Siddhartha, St Francis of Assisi, Titus Alone—or even, through a different lens, The Truman Show. How would this hypothesis unfold within the pre-Reformation, pre-Enlightenment insular political and social landscape of medieval England, some aspects of which seem to echo post-Heian Japan?

Progressing from The Estate, to The Village, The Monastery, The Town, and The Return, the novel’s narrative arc is an exploration of mysticism and anarchy, encompassing a journey of faith, passing through innocence, experience, suffering and redemption, with unpredictable twists of fate amid a turbulent and often brutal era of plague, serf revolts, and inquisitions. (Why were heretics ceremonially burned at the stake? Because the Church had a strict injunction against the shedding of blood…) However, despite its graphically violent context, this saga is not one that is destined for a transfiguration into cinema or an action manga/anime adaptation. It’s more of a throwback to the long-respected classic expository literature of ideas (“in the tradition of Plato and Berkeley”), fleshed out in representative characters who engage in earnest conversations and debate, liberally sprinkled with subliminal allusions to an impressively diverse and vast array of archival sources, historians, theologians, philosophers, poets, playwrights and other thinkers and scholars of note, past and present—supported by some 50 pages of densely detailed annotations. Close reading reveals for example the (Zen) classic Ten Ox-herding Pictures reworked as a Christian abbot’s sermon, suggesting that the secluded and austere orthodox European monastic regimen of prayer might have equal potential for the satori that may arise from the wholehearted Linji/Rinzai practice of zazen.

Evanoff is drawn to the archetype of “the return,” as referenced by Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces. After temptation and breakthrough in the wilderness, Jesus returns to preach the Sermon on the Mount. After achieving enlightenment the Buddha returns to deliver his first sermon at Benares. After the sage in the Ten Ox-herding Pictures “reaches the source,” he returns to society, blending into the market throng. After the Boddhisattva glimpses the other shore, he returns to the world, vowing not to enter Nirvana himself until he can take everyone with him.

The search for a meaningful and morally justified existence, both individually and within society, is timeless, presumably even preceding the remarkable efflorescence of woke consciousness that arose in the 6th century BC: Confucius, Laozi (Lao-tzu), Heraclitus, Pythagoras, Thales, Gautama, Mahavira. However, One with the Father demonstrates how critically the contemporary sociopolitical context impacts any seeker’s trajectory. Some enlightened souls succeed in bequeathing a movement, a path for followers to have faith in; how many others may simply have been in the wrong place at the wrong time and subsequently are no longer remembered? Meanwhile, how many formerly heretical beliefs have survived over centuries, incrementally metamorphosing into present-day orthodoxies?

This is not a book for everyone, but for attentive and thoughtful readers, it may function as a deeply-layered allegory offering much to reflect on.

Ken Rodgers is KJ’s managing editor. He and Richard Evanoff met for the first (and only) time at Allen Ginsburg’s historic ‘Howl’ reading at Seibu Kodo, Kyoto, in 1988.