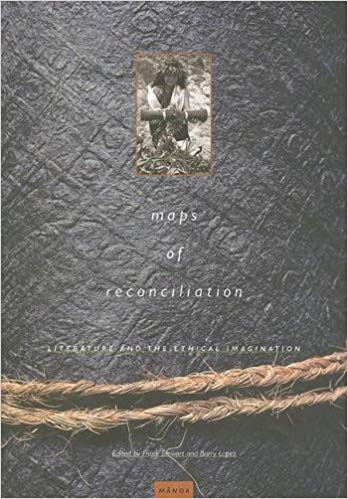

Maps of Reconciliation – Literature and the Ethical Imagination

ed. Frank Stewart & Barry Lopez, Mãnoa 20:1, University of Hawai’i Press 2008

[R]econciliation is a work in progress, as attested to by the recent history of international criminal tribunals or truth and reconciliation commissions from the former Yugoslavia to Sierra Leone. Neither the tribunal in the former Yugoslavia nor the commission in Sierra Leone has completed its work: both have been running for a decade or more. Yet, despite their flawed and protracted nature, activists, academics and citizens across the world are now starting to demand that these strange, complex processes be set up for both Sudan and the United States’ violations in Iraq and the prisons at Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay.

Cambodia is yet another country currently struggling to heal from and come to terms with the genocide and crimes against humanity perpetrated there. As if this history were not difficult enough, its citizens are being walked through a legal minefield. They now have to try to comprehend notions of justice, fair trial processes and legal rights as defined by the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, the court set up in 2001 to try former high-ranking officials of the Khmer Rouge.

These are positivist processes in that their bold and ambitious promises are delivered in the form of hefty paperwork cataloguing complex legal rules: everything is written out. There are caveats of course, and the promises come with fine print — rules to explain rules.

One wonders then, what happens to survivors — heroes and victims alike — who have to get on with the everyday business of living while these tragicomic machinations play themselves out. How do you deal with trauma until this or that civil society organization and tribunal comes to you with promises to heal your wounds?

Mãnoa’s Maps of Reconciliation is a compendium of writings and images that grapple with this very difficult question. Nine out of eighteen essays found in this anthology are reprints, some of which were written in the mid-1990s. There is something revelatory about this decision on the part of editors Frank Stewart (co-founder and principal editor of the journal) and Barry Lopez.

This is an issue that looks ahead or forwards to imagine and create realities that are an appropriate response to what guest editor Barry Lopez calls the “vetted doctrines and the ruthlessness of reason,” (p. ix, Editor’s Note) that we have thus far been subject to and find ourselves complicit in propagating. Yet, in this issue we are very much looking backwards, turning our heads and opening our ears to see and hear the reiterations for reconciliation and peace found in the essays, poems, plays and photographs of writers and artists who have been uttering it for decades.

What are we not hearing? Why is there an absence of dialogue between the people who craft legislation and set up tribunals or commissions and the artists who speak for their communities? Why do these legislators and administrators not look deeper at the collective acts of engaging in indigenous, local and deeply personal forms of reconciliation — a word that at any rate may be untranslatable into languages other than English? The essays in this edition of Mãnoa do not profess to answer this question or redress this gap, this lack of communication. Instead, as a whole, they fill the void created by a one-size-fits-all approach to justice, peace and reconciliation concocted by governments and the United Nations.

All three photographic essays in this collection quite appropriately detail rituals of reconnection, community and identity among indigenous Hawaiians. Italian-American Franco Salmoiraghi’s black and white portraits are quiet glimpses of Hawaii’s communities engaged in various rituals of reclamation, reconciliation and the linking of generations past and present. Taken from 1989 to 1993, they invite the reader into a story, detailed frame-by-frame. And yet, we are looking from the outside in and they conceal as much as they reveal: these private affairs are not meant to be scrutinized by onlookers.

The essays themselves deal with desecration and restitution (Honokahua) of burial grounds and spiritual forefathers; the struggle for sovereignty and self-determination, symbolized by Queen Lili’uokalani’s struggle for her people; and finally that theme which runs through every page in Maps: remembering and passing down stories as an act of continuity in the face of destructive changes (Ho’oku’ikhai: To Unify as One). This final essay reminds us, “It was a shout to assemble, for in retelling our past, we honour our forefathers. They live through us — in our songs and our stories, and in who we are” (p. 190).

However, Wayne Karlin’s essay “Wandering Souls” and Galsan Tschinag’s powerful oral narrative “The Tamyrs: A Tale of Two Peoples” are the powerful core of this issue. Both tell stories of past atrocities which linger like cancerous growths, slowly eating away at the possibility of a normal life for the perpetrators and their progeny. Karlin’s essay on a Vietnam War veteran’s efforts to come to terms with the fact that he killed a newly drafted, innocent Vietcong soldier may not be uncommon or rare in the facts it relates. But the tenderness with which he writes about veteran Homer’s guilt and pain, as well as the way in which he re-creates Hoang Ngoc Dam, the Vietnamese soldier whom Homer killed, makes this the strongest piece in the collection. The final scene of ritual reconciliation is the kind of future that editor Barry Lopez wants us to imagine in the aftermath of so much conflict.

Tschinag’s essay on the other hand, speaks of ancient tribal hatred between the Kazakhs and minority Tuvan peoples. Scene after scene details how resistant to reconciliation two men from the two warring tribes are until both are forced to work, fight and protect each other as soldiers in the military. If the native Hawaiian essays urge us to remember our pasts and honour our forefathers, Tschinag’s essay reminds us to not carry the hatred of our forefathers forward into future generations, but the tale is told without moralizing or prescribing a way of being.

Similarly, Prafulla Roy’s snapshot of Bombay after the Hindu-Muslim riots and violence in his essay “India” asks us whether we could in fact forgive a collective, unseen enemy in the immediate aftermath of a tragedy. Did any Hindus protect Muslims from enraged Hindu rioters and murderers when the violence broke out? Did the Muslims do the same for the Hindus? Roy answers us in the affirmative, but not without first addressing the immense leap it takes to move from hate to compassion.

This impressive collection rarely slackens in its intensity, though some additions like Luis H. Francia’s “Meditation #7: Prayer for Peace” and Julia Martin’s “Wonderwerk” seem to sum up the complexities of reconciliation with sweeping and benign turns of phrase (Francia’s poem), or depend too much on repetition and abstraction to instill a sense of wonder about the past’s connectedness to the present (Martin’s essay). Playwright Catherine Filloux’s 1996 play) “Eyes of the Heart” focuses on the impact of the Khmer Rouge on Cambodians (one of four such plays she has written). While it is interesting in that Filloux drew from real cases of Cambodian trauma victims who were blind (chose not to see?) for a while, it’s an awkward addition to a collection that otherwise flows seamlessly. Filloux’s play is topically interesting, but lacks the power of some of the other pieces in this edition.

Overall, this is a marvelous issue of Mãnoa that carries us from the Pacific Islands to Asia, South Africa and Latin America to provide readers with a brief, but entirely resonant glimpse into rituals of reconciliation. One wonders whether copies should be sent to tribunal and truth commission administrators.