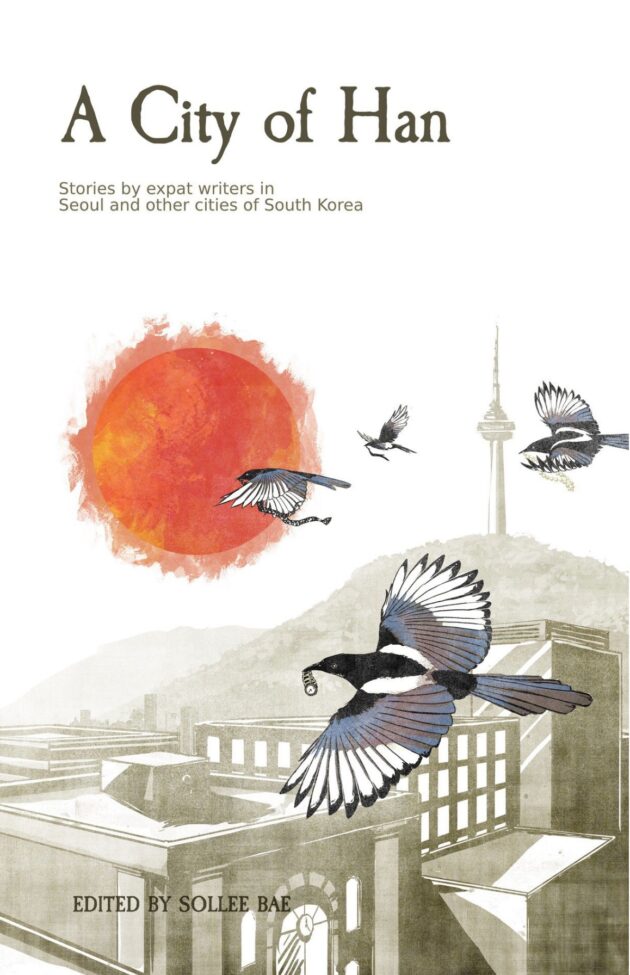

A City of Han: Stories by expat writers in Seoul and other cities of South Korea, edited by Sollee Bae. Seoul: FWS Publishing, 2020. 121 pp., ¥1059 (paper).

In this era of extreme global hypersensitivity to race and national narratives, it is arguably a high-risk proposition for a Western expat author in Asia to write about such things. Yet two of the authors represented in this volume of expat short stories from South Korea, Gord Sellar and Ron Bandun, fearlessly walk the ideological plank of their own privilege and manage to say something that is provocative rather than condescending about race in Asia.

In Sellar’s ‘Sojourn’ we step unexpectedly into a future world where “genetic deviants” with special powers coexist side by side with normal people who discriminate against them. The unlikely backdrop for this psychic sci-fi tale is a hagwon (cram school) where the story’s protagonist, Trevor, works as a teacher. Sellar breathes fresh life into this well-trodden corner of expat existence by overlaying a unique magical dimension. The seemingly unremarkable, nerdy Canadian narrator has a superpower that allows him to perceive nature’s invisible microbial frequencies and, we later discover, manipulate them. This character’s richer perception of his surroundings heightens his appreciation of the world. On his walk to work, for example, Trevor passes a rice field: “a patch of viridian dropped onto the edge of a grungy neighborhood.” Due to the narrator’s enhanced perception and Sellar’s evocative prose this becomes as rich a sensory experience for the reader as it does for the character.

For Trevor, the field shone, as luminous as the midsummer sun above. Its simultaneous exhalations of carbon dioxide, methane, and oxygen were as sensuous as a warm bath, the rippling aggregate consciousness of the microbial stew as colorful as any masterpiece on a museum wall.

As a waegukin or foreigner in Korea, Trevor is already positioned on the margins of the dominant culture but as he is also a mutant his status as an outsider is twofold. Korean society discriminates against “genetic deviants” and their migration to the country is forbidden meaning that Trevor had to hide his status as a mutant to enter the country. An incident with a levitating pencil case finally results in him being exposed, although it is actually another mutant, a Korean student, Soo-jin, who is the guilty party. Yet as Trevor is a foreigner and was present when the pencil case rose he is the first to be blamed. His boss, “hadn’t imagined for an instant that it had been Soo-jin who’d done it. She’d assumed he had to be the deviant, that it had to be the foreigner in the room.”

Thus, the story becomes a clever way for the author to explore issues of race, perception, discrimination, and the cultural status of foreigners in Korea.

Early in her introduction to A City of Han, editor Sollee Bae addresses the issue of Seoul being largely overlooked due to a perceived lack of a defining character: “If we were to compare it to a person, it would be that man or woman who worked for a marketing firm, dressed sensibly, and carried the last year’s model of iPhone (but no older).”

Ron Bandun’s ‘Kyungsung Loop’ also tackles the issue of race and power in Korea. This time we see racism directed against Koreans by the colonial Japanese who justify their rule of the peninsula with a myth of racial superiority. The story is told from the point of view of one of one of these colonialists, a Japanese civil engineer, Nishimura Hidemitsu, who lives in Seoul. It starts in the early 1930s, during the height of Japanese rule, when Nishimura meets a Korean man from the countryside while riding the train and the two become fast friends. The interactions between the two men, are, by and large, nuanced and natural,which gives the reader a clear view of the inequalities implicit in the colonial relationship without resorting to stereotypes of either the colonizer or the colonized. There are many moments when the colonizer, Nishimura, shows kindness toward his Korean friend, although the unexamined manner in which he condescends to him is more shocking for its assumed naturalness.

Language as an instrument of colonial oppression by the Japanese in Korea is well documented and it permeates the exchanges between the two characters:

“I’m Hwang-bo,” he replied, moving closer to sit next to me. The heavy stench of garlic and brine hung from the rags he wore. But I smiled anyway.

“That’s quite a difficult name to say,” I told him.

“You need a Japanese name.”

“Do you have any suggestions?” he asked.

“I will call you Ushi-san,” I said.

The story ends in 1945 shortly after the end of the war, by which time the remaining colonialists including Nishimura and his family are desperately seeking to escape Seoul and return to Japan. Trying to buy their tickets amid the post-war chaos at the station, Nishimura runs into his old friend who is now the station master. The final and somewhat touching interaction between the two men again uses language to denote the much-changed power dynamic between Japanese and Koreans.

“Ushi-san!” I exclaimed. “They put you in charge?”

It took a moment for him to recall my name. “Nishimura Hidemitsu,” he said. “My name is Hwang-bo now, and this is Yongsan Station.”

Free of the colonial yoke, Hwang-bo asserts his new identity, and in a gesture of benevolence gives Nishimura four train tickets so he and his family can escape the city.

I got to my hands and knees blabbering my gratitude in front of my wife and children.

“It’s okay. This is not a sad moment,” Hwang-bo said, helping me to my feet. “It is a new era for our nation.”

Early in her introduction to A City of Han, editor Sollee Bae addresses the issue of Seoul being largely overlooked due to a perceived lack of a defining character: “If we were to compare it to a person, it would be that man or woman who worked for a marketing firm, dressed sensibly, and carried the last year’s model of iPhone (but no older).” Yet Bae sees the city’s apparent blandness as something to be embraced rather than rejected, and all six short stories in this collection demonstrate how a subdued palate can sometimes offer more to an artist than even the brightest colors.

Review by Simon Scott