Poems for the Unborn / 生まれぬ者への詩 by John Solt. Translated by Aoki Eiko – reviewed by Taylor Mignon

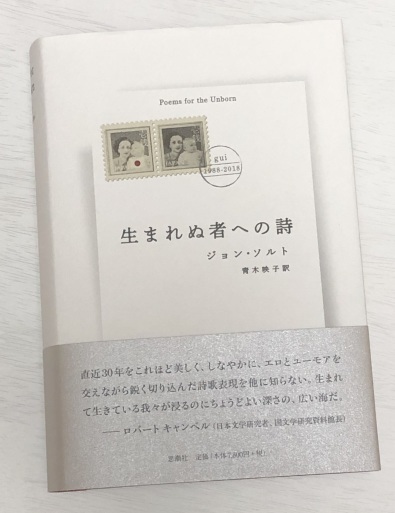

Poems for the Unborn / 生まれぬ者への詩by John Solt. Translated by Aoki Eiko. Tokyo: Shichosha, 702 pp., ¥8580 (cloth).

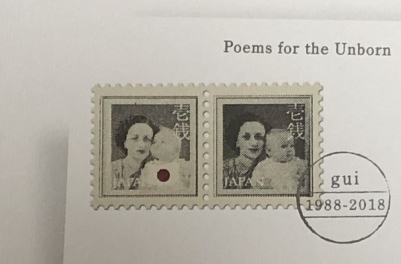

Best known as a “Japanologist” (a term he might reject) for his critical study Shredding the Tapestry of Meaning: The Life and Poetics of Kitasono Katue, John Solt is less known for his poetry. This collection, Poems for the Unborn, lovingly, methodically, assembled and presented here bilingually in hardcover, a coup of book design by Tetsuo Haketa, is drawn from the contributions Solt has made over 30 years to the private coterie organ, gui, an ongoing journal based in Tokyo.

Kitasono’s influence on Solt is evident in this volume as gui was edited by Tatsu Okunari, one of the youngest members of Kitasono’s private group, VOU. Another way in which Kitasono’s presence is felt in the more than seven-hundred pages that make up this work is that many of Solt’s poems are homages to Kitasono and other VOU members such as poet Shōzō Torii and visual poet Shohachiro Takahashi. Homage has a secure place in the history of avant-garde poetry, but here they are less experimental than heartfelt acts of intimacy. Section III of this long poem for Takahashi, for example, simply depicts a scene, but then takes a psychedelic turn:

we hadn’t met for years / maybe centuries / and spent what seemed /

like a fortune / during the long silence / in the garden / then you tore along / the perforation / around my skull / revealing a wide crevice / in the dream

Section IV also succeeds in presenting a scene matter-of-factly in its concrete particulars before shifting gears:

Wind at the deserted / Temple of Heavenly Virtue / on the outskirts of Akita / the monk’s off drumbeat / and staccato sutra chanting / blanketed by shrill cicadas / in his disengagement / the monk unplugs the planet / the scene spills like sand / into a transparent envelope

The dreamlike aspects of the poem are presented as if they were literal: the monk just pulled out the planet’s plug. The following image, a simile, “like sand,” seems also as though it could also be actual. What is most notable here is that Solt, a North American poet, is writing in service of Japanese artists; usually it is the Japanese who are writing about their Western counterparts. Solt’s poetry, in recognizing Japanese artists and their contributions to the world beyond Japan, takes a step toward correcting that imbalance.

The contents of the book are made bilingual by Eiko Aoki’s diligent efforts while closely being aided by her querying with the poet to confirm the works’ contents. For a translator to take care to engage with the poet must be especially gratifying. After all, what translator would automatically assume their translations are always spot on? An arrogant one I would hazard.

Solt’s poetry in many ways reminds one of Cid Corman’s; the lines, stanzas or poems themselves are often quite short; their “meanings” are fleeting yet resonant thoughts and images that are often so easy to grasp that we might overlook their import. This one is almost a senryu, yet it brings to mind Charles Olson’s edict: “one thought per breath or line”:

i’m so sleepy

my head has a widening hole

through which words fall

What is refreshing here as with all Solt’s first person poems, is the lower-case “i.” Many American poets could learn from this how to dial back their egos. It is evident that Solt learned lessons like this one from the Asians he has read. Where Solt distinguishes himself from Corman is in his radical—one might say hippie—attitude and humor:

the meaning of life

is revealed clearest

in the incremental

accumulation

of orgasms

It isn’t the accumulation of material things, silly!

Some of the poems here come in the form of fully crystalized dictums that ring delectably (and in this case alliteratively) true:

the toilet of poverty / the pantry of poetry.

Solt also offers us an homage to the photographer-poet Ira Cohen who took stunningly yet elegantly engaging portraits of Kazuko Shiraishi and butoh dancer Kazuo Ohno; an homage for the “Bob Dylan of Japan,” Maki Asakawa; to samisen player Fuei Nishimatsu, and to a poet much loved by this reviewer, Shōzō Torii. Add to the poetry Solt’s visual poems, stamps, assemblages, reproductions of covers of gui and postcards, and we finish, joyously, with a book that looks just as good as it reads, and that will allow us to pay closer attention to this overlooked psychedelic poet-scholar-translator-Taoist-philosopher critic of the world and humanity. Solt’s work is rich with eroticism, and a refreshing sense of self-deprecation and is always generous to the people he loves. At times a hippie, at others a satirist, but more than either of those, Solt is a poet. This collection of thirty years of work will astonish those with open hearts and minds. Few can match Solt’s elegant, unique, and possibly enlightened, aplomb.