Tokyo Poetry Journal, Vol. 5. Japan and the Beats. Ed. Taylor Mignon, 2018.

The whole matter of Beat Lit/Beat Culture’s engagement with Japan has been overdue for thoughtful attention for too long. With writing on Beat Generation personalities and their work at near-saturation point in English, Japan’s pivotal informative role in helping incubate Beat ethics, aesthetics, and insight practices especially has remained oddly elusive. Geographical distance plays a role in this. Few cities and decent-sized towns in North America are without a “Zen” café or fashion boutique nowadays; but even as the popularity of Beat-era writers Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and Gary Snyder continues to soar, actual knowledge of what a term such as Zen might properly mean is skimpy. Globally, current generational interests in Asia palpate toward yoga, sushi, and beach & trekking holidays in Thailand and Bali, yet remain coy when it comes to matters of deep cultural immersion: that takes commitment. In Japan, however, the small current of Westerners drawn there in the post-war 1950s when it was one of few Asian-Pacific nations one could consider settling in to teach or study, expatriates found themselves in the presence of a deep and antique culture.

Those pursuing serious literary, artistic or spiritual inquiries were compelled to acknowledge its prevailing Buddho-Shinto-Confucian ethical underpinnings. As R.H. Blyth discovered before them, to study haiku for example, was to be drawn irreducibly toward its informing cultural and spiritual elements. Zen, sacramental wandering, the Tao of Tea, martial traditions, poetry and calligraphy, notions of friendship and loneliness—all were vivid cultural signifiers in Japan that could not be ignored. Other important literary ambassadors who followed—Gary Snyder, Donald Richie, Kenneth Rexroth et al— understood that they needed to see more deeply; they readily absorbed what they encountered en route. As Ken Kesey might have put it in San Francisco, you were either on the bus or you weren’t. Accordingly, in this volume Taylor Mignon, current Editor-in-Chief of ToPoJo and a former editor at Printed Matter, has worked to illustrate what it has meant to think, live, work, emulate, and yearn after Beat Lit/Beat Culture in Japan from both East and Western cross-cultural vantage points.

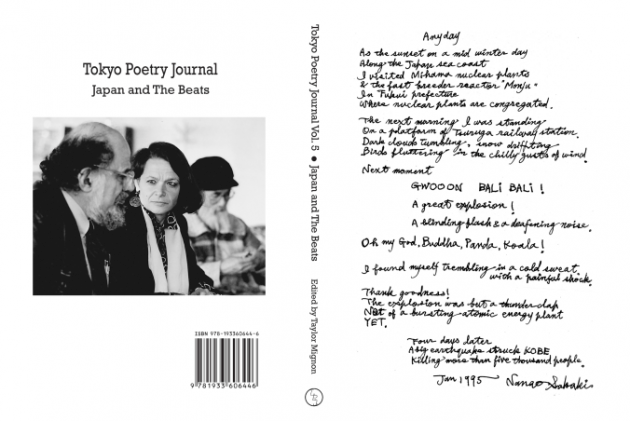

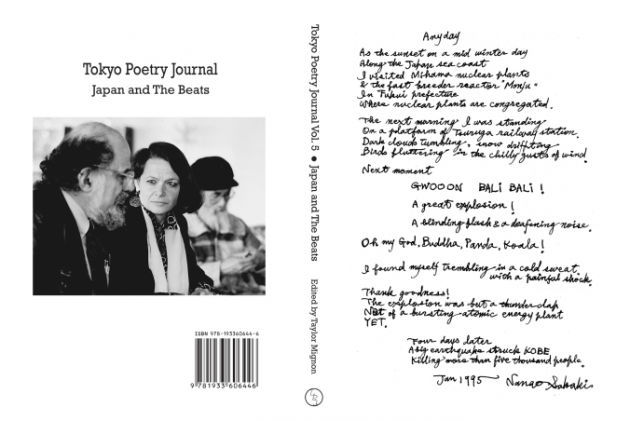

Featuring the text of Nanao Sakaki’s poem “Anyday” in his own unmistakeable handwriting, the edition’s front cover prompts realization that, in Japan, Beat has not simply been an American phenomenon. Sakaki, a wacky, intensely eco-literate bard of world-wide mountain ranges and urban canyons, personifies virtually everything associated with Beat Lit and Culture in Japan. Paralleled in renown and notoriety by Vancouver-born, poet/wild-thing Kazuko Shiraishi, the pair have given Japan an utterly idiosyncratic, one-two punch unrivalled in Beat annals anywhere. In a landscape pioneered by Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, Kerouac, W.S. Burroughs, Joanne Kyger, Snyder and others, that takes some doing. Yet no other place outside the U.S.—Paris, Tangier, India, Vancouver—has had the enduring resonance of place in Beat literature enjoyed by Japan. Both Shiraishi and Sakaki shine forcefully in this valuable, original edition.

Mignon’s introduction establishes his terrain and details useful Nipponese linkages, noting a series of journals and magazines, Japanese and English language alike, that shaped lineage paths for a cluster of Beat-oriented/influenced writers and editors. As we move well beyond the old post-war generation literary influences of Donald Keene and Edward Seidensticker, this has needed crystallizing for outsiders especially. Rexroth’s work is given a worthy discussion, and his disciples John Solt, Morgan Gibson, and Sam Hamill are acknowledged as the web of associations broadens. Younger neo-beat writers get a drum-roll too. Mignon dubs his collection a “definitive primer chock full of deep Beatitude.”

In truth, the roster of contributors is substantial. Familiar East-West Lit veterans include the inestimable Cid Corman, heavyweight Tanikawa Shuntaro, Leza Lowitz, Keida Yusuke, and the late-Hillel Wright and Edith Shiffert respectively. Ira Cohen offers a nutty poem “Tokyo Birdhouse” for Shiraishi, and Anne Waldman has an epitaph for Nanao. What unfolds is grab-bag of poetry, prose, elegy, encomia, letters, a music score, photos and drawings, the lot.

Robert Lee provides an excellent essay in appreciation of poet Shiraishi that positions the late-night mojo dynamo she is, and long has been, within a matrix of poetic, Shinjuku/NYC jazz bars, dance, and multi-media energies. There’s simply nobody like her. Four of her poems in translation, her essay on Rexroth, and an interview of hers with Sakaki are also featured. Here’s a taste from “My America”:

…you’ve got that barbeque bubbling up

With love

Delicious goo

So good in bed

I like the inside of your thigh

Your tough elegant penis

That doesn’t let anything on

Wipes out the gods

O let me say my prayers

At a time like this

Oh dear, what did Japan’s literary guardians think of that in its day?

Shiraishi’s essay on Rexroth is as perceptive as it gets. She understands him in a profound sense as poet-colleague and remembers his early championing of Ginsberg’s oracular, dharma poetics, as well as Rexroth the Santa Barbara professor whose noble gesture allowed Vietnam War-era students to assign their own A-level grades; it deferred them from military conscription. It’s a superb pensée, indeed an elegy that shows old master Rexroth and Japanese Lit in a recursive two-step; as an early, definitive devotee and translator of Japanese poetry he was instrumental in kick-starting the East-West poetic incubator that has steadily blossomed to its present condition of existence.

David Cozy relates in a fine essay that, unlike all the others, Sakaki-san remains known almost universally by his familiar name, Nanao. While the two never met, Cozy emphasizes Sakaki’s approach to addressing his abiding poetic concern with wild nature, in fact the wilder the better. The sense we get is of a crafty trickster; but Nanao was, studying his craft in English assiduously, rising at dawn after nights of revelry to prepare carefully for his public readings and appearances. There’s no mistaking Beat life here for slackerism; young wannabees make note.

A letter from Tanikawa Shuntaro on Allen Ginsberg’s death in 1997 admiringly explains “I hope you’ll forgive me that in my mourning for you, rather than the things you wrote, it is the warmth of your personality that I remember most…when I think of that warmth, I find myself believing it the wellspring of your poetry.” Warm human connections between Ginsberg and Japanese writers were obviously reciprocal. It was in Japan in 1963 where, after a year and a half in India, and through Gary Snyder, Ginsberg met Sakaki and his Shinjuku and rural tribal mates, informally known as the Bum Academy. He would return to North America via the historic Vancouver Poetry Conference bringing alterative ideas of community that would find a hearing within the San Francisco countercultural project during the Sixties; several years later, Snyder’s writing in Earth House Hold about his experience in Japan, particularly “Why Tribe” and about Sakaki’s Suwa-no-Se Island commune, articulated further, critical trans-Pacific ideas to America’s own back-to-the-land movement.

In “Considering Joanne Kyger in Kyoto,” Linda Russo comments on Kyger’s long friendship and correspondence with Philip Whalen, most notably throughout her Kyoto years in the early 1960s. While Whalen’s own Scenes of Life at the Capital stands as a landmark title, Kyger’s own first book The Tapestry and the Web would be fully developed as a result of her four-year tenure in Kyoto. Russo questions what the role of Japan was on Kyger and offers a collegial nod to Cedar Sigo’s recently edited publication There You Are: Interviews, Journals, and Ephemera (Wave Books, Seattle) that stands as a composite biography of this remarkable, unaccountably critically-neglected major poet. Russo writes, “The story of Joanne Kyger’s life is, and is in, the poems, which take up the small details of daily life with deep awareness, humour, and grace. It is the story of inhabiting a landscape and a bioregion and making it a home.” Kyoto, she clarifies, was “the site of this making.” While it imbued Kyger’s work with Buddhist awareness, it was also, she quotes Kyger in saying, “very restrictive.” Language was at issue; so was the business of daily housekeeping. The roamings Kyger undertook with her then-husband Snyder led her to “near-inaccessible locations.” These were not café Zen devotees: references to Han Shan, Basho and other monastic bards and wanderers, in addition to prominent cultural and ecological locations percolate throughout Kyger’s Tapestry work that appeared in 1965 and that assure its place at the heart of the East-West/dharma/ Beat Lit that flourished following the initial Beat encounter with Japan.

This brings inescapable rise to the matter of Gary Snyder’s stature within the ongoing Beat/Japan legacy. His presence flows through the volume but is perhaps calculatedly subdued. A short piece by Simon Scott recollects Snyder’s resounding Buddhist and ecological influence on Jack Kerouac that is recalled in The Dharma Bums. It explains what you need to know, to listen in with some familiarity in a discussion involving these titans. Otherwise, Snyder is accorded comparatively little treatment. Mignon concedes his collection is not comprehensive and that certain names are absent or nearly so—Sō Sakon, Suwa Yū, Nakagami Tetsuo, Whalen, Diane di Prima, and more of Ginsberg and Snyder. His hope, he says, is to “contribute to ongoing conversations about these important poets.” In that, he more than delivers.

Beat Lit/Beat Culture isn’t for everybody; it can take some acclimatization. For newer interests, this edition is bonanza. Almost inevitably, poetry selections by current neo-beats are uneven; however, Holly Lanasolyluna has a good one in “Breakfast in Neo-Tokyo,” and Frank Spignese’s “Death of a Fisherman, for Hillel Wright” is a raunchy, honest-sounding tribute to this character who loved boats and the salty life. Wright’s own poem “Dreaming of Allen Ginsberg” situates things well: “In the dream Allen was on the JR Nambu Line/between Kawasaki and Shinagawa…” Joy Waller gets off some catchy, bitchy licks in “Mode on / Mode off”, and Jessica Goodfellow registers with “Alphabet Confetti.” Could there be a Japan/Beats collection without Fujiyama? Hirata Natsuko obliges intelligently, open field-style with “Foggy Mt. Fuji.”

As always, there is the heart: the late centenarian Edith Shiffert, beloved by many in Kyoto slips gently into focus with lines as fine as any in Emily Dickinson with “Under The Trees, Transcendentalist”: “Old hag, goddess dying,/walks in a forest/just on the level ground./Suddenly she forgets her feet/and rises, rises./…oh this is ecstasy enough/with or without a fall.” And as if in response, AJ Dickinson observes in six simple lines “for Edith Shiffert”: a candle / incense blossoms / for Edith /…101 goodbyes/Kyoto beats / passings.

Physicist Fritjof Capra of The Tao of Physics and other masterworks has rightly argued that “our generation’s version of Buddhism will be ecology.” With much of contemporary environmental discourse seasoned with ecological awareness inspired by Buddho-Daoist and South Asian wisdom paths, it would be good to see one powerful essay, say, on poetry and nature consciousness from Beat Japan. Such work has been done elsewhere and the work of Snyder, Hamill, and the great deal of brilliant reportage that has appeared in Kyoto Journal, may account for its absence here.

Still, it deserves attention in the kind of more comprehensive follow-up edition he must now surely be contemplating. This, and some fuller foraging into how foreign writers adapted to, and adopted, a deeper view of Buddhism through their time in Japan would be meritorious stuff. But what Mignon has carpentered in this welcome book edition already commands respect. It’s a new keeper on any shelf of serious East-East literature.