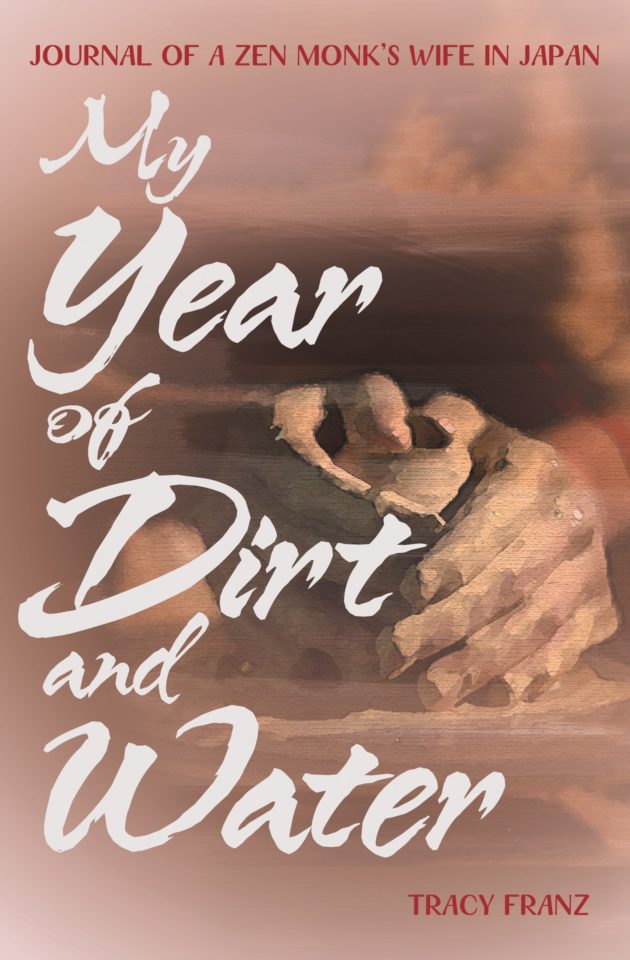

My Year of Dirt and Water: Journal of a Zen Monk’s Wife in Japan by Tracy Franz

In understanding another culture, there are layers of learning, and the more you know, the more complicated it becomes. This is nowhere more true than in Japan. And the foreigners who live here watch each other, gauging their respective levels, ever mindful of their own experiences and the assumptions they have gleaned from them. This book’s peculiar interest is that it holds up a mirror to every layer of Japan that may be experienced.

Even before the first page has been turned, My Year of Dirt invites the reader to indulge in his (or her) assumptions. First, the publisher, Stone Bridge Press, is famous for books on Japan, treating of culture and self improvement based on exposure to this evocative culture. If you pick up a Stone Bridge Press book, you probably already know a bit about Japan and are looking to learn more.

Then, in the title appear the words “Zen monk.” Immediately a picture is formed, perhaps of a black-robed, straw-hatted figure hurrying through the rain. Sifting through the title, one may cobble together the phrase “A Year in Japan.” Might this author be one of the many who come to Japan, prepared to endure a difficult alien culture in order to approach an answer to the conundrum of life, which she has been told may be found here? None of the above. For this is a book that, once begun, sends assumptions tumbling, one after the other. The prospective reader may have experience in the three main journeys the author takes—Zen, traditional art, and life in Japan—but the Zen monk and his wife are not Japanese but American; she is a novice in neither karate nor pottery; they are not new to Japan, but veterans of some years’ standing.

The author says she embarked on this year in Japan in order to undertake a spiritual practice of her own. She must occupy herself while her husband seeks Soto Zen priestly credentials by training in a nearby monastery, so she joins a pottery class as a deshi (disciple) of the elderly female teacher. But she cannot seem to make the dirt and water come together to make a smooth clay, either physically or metaphorically.

Foreigners living in Japan must face the fact that this monolithic presence, Japan, will not allow us to “fit in,” as if this were an actual goal instead of an elusive ideal that one tries to castigate and persuade oneself into. People come to terms with this in different ways. The author makes it something of a refrain (“They’ll never forgive us for being foreigners”), but at least a Japanese friend lightens the mood by admitting that the Japanese themselves struggle to fit in.

During the year, the author has various uncomfortable experiences. She visits her husband’s monastery, and is cramped by rules, the doubts of the priests in charge, and the constant pressure to work and be useful. She teaches English at a women’s college, where she fields the laughably innocent questions of the students and fellow teachers. She lets off steam at a karate dojo, enduring the resulting aches and pains. And she attends pottery class, where time after time her work is swept off the wheel into the scrap bucket by the teacher who scolds, “The basics! The basics!” I can sympathize. Life in Japan, for the dedicated foreigner, can quickly deteriorate from the hopeful life slogan of “Every day something to learn” to a more melancholy “Every day something to be tested on.”

These outer experiences are like clothespins to hang out her inner life, which is fraught with a negativity born equally of loneliness, self-doubt, and a hinted-at unhappy childhood. I have to say that her knowledge of Zen, and her practice of traditional arts, don’t seem to stand her in very good stead when it comes to supporting her psychologically—at least not during this year.

The author’s husband, describing Zen, says, “This kind of practice strips away everything and reveals the mind very clearly.” Certainly the author’s mind is clearly revealed in this journal. The central themes—the nature of experience, reality, and memory; the Zen conundrum of goals vs. no goals; physical discomfort; loneliness and failure—pile up in a jumbled heap. This is the author’s “A Year in the Life”, with all its pains, and occasional glimpses of beauty. Tearing down, however, must at some point give way to rebuilding. Laying bare the chaos must lead to producing order. We don’t get to see what form this next step will take for her—but this is a memoir of her youth, and we are free to imagine what happens later.

For me, what saves the book from gloom, and what probably saved the author as well at the time, is the frequent mention of her friends. Japanese and foreign, men and women, past and present, who encourage, offer insights, bring gifts, and try to answer her agonized questions. They are the hidden root of gratitude running at the bottom of all her pain. And herein lies a bright nugget of truth. If one cannot “fit in” with Japan as a whole, surely one can find a small, blessed circle of friends to fit in with. Finally, a technical note. Many Japanese words, some of them very specialized, are used in the text, and the definitions are scattered randomly. I think a glossary would be a great help, whatever level the reader may be in with regard to Japan.

Rebecca Otowa is a frequent contributor to Kyoto Journal and the author of “At Home in Japan: A Foreign Woman’s Journey of Discovery.”