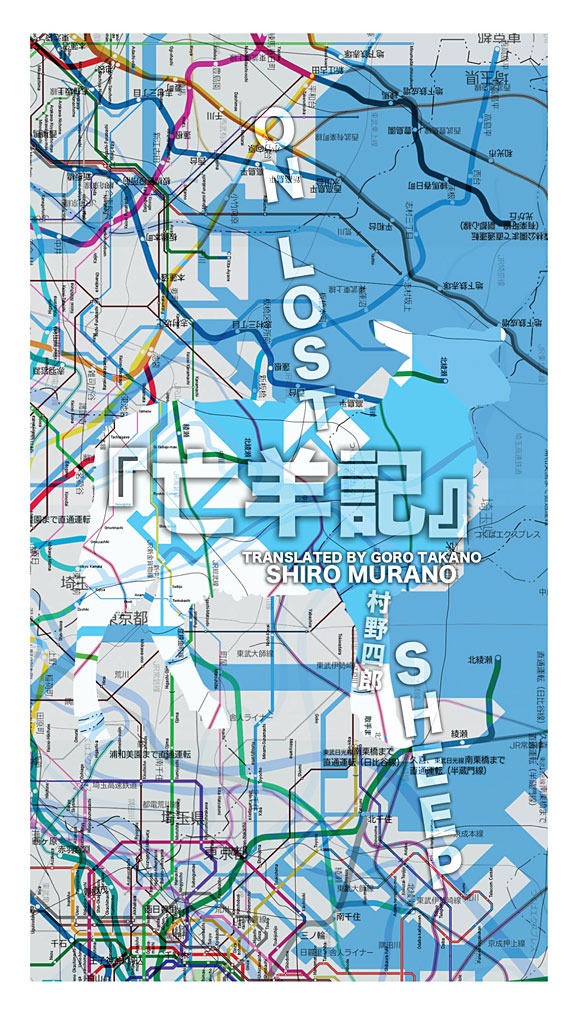

On Lost Sheep by Shiro Murano. Translated by Goro Takano. Hawaii: Tinfish Press, 101 pp., price $18.00 (paper).

On Lost Sheep by Shiro Murano. Translated by Goro Takano. Hawaii: Tinfish Press, 101 pp., price $18.00 (paper).

Translating out of one’s original language into a second language is a risky endeavor. In the case of translator Goro Takano, with this exquisite and slightly quirky bilingual chapbook-object, he acquits himself well. The edition is important because it brings into English a master among Japanese modernist poets, one who may now be considered among the ranks of Junzaburo Nishiwaki , Takiguchi Shuzo (critic and artist) and Katsue Kitazono. This is, to my knowledge, the first time Murano’s poetry has been made accessible in English in book form.

The first work, of fifteen lines in four stanzas and subtitled as the preface, “The Effigy of a Poet,” offers a nuanced impression of the surrealist method of anthropomorphism, particularly in this third stanza:

The blood prepared for death

Colors a landscape and

The shriek of a bulbul rends

The entire universe without making any sense

Though we might ask if the second line should end in “and,” Murano finely describes an abstract image of nature, offering the reader resonant imagery. (This stanza could remind the reader of John Keats’ idea of Negative Capability.) The second to last line of the poem (just after the stanza quoted) is a mini-symphony of assonance and alliteration, expertly expressed:

(On such a day)

With vines of winter berry whining around it

A personal poetic pet peeve of mine is when poets decorate their works with excessive punctuation. Smartly and economically, Takano uses the sparse approach, eschewing commas at the end of lines, for example, since the spaces after the words themselves stand obliquely for commas.

When reviewing a book of poems, the review is inevitably driven by the critical preferences of the reviewer. In this way, it is both critical and personal, a useful method of pondering poetry.

When I translated the complete body of Torii Shozo’s surrealist verse, I followed some guidelines. First, generally, the overall intentions of the poet must be honored. Another point is that the sequence of events or images (as expressed by nouns, verbs, adjectives and so on) should be placed in the original order, unless the expression draws too much attention to itself. It is crucial, too, to avoiding padding, or adding words to make the work easier to comprehend.

The most important point is to not add anything that is not in the original poem: a translator should not explain the poem in the poem. Since many believe that non-Japanese, particularly Westerners, aren’t able to grasp Japanese culture, the temptation can be great to do so. Nihonjinron—the theory of the uniqueness of Japan—may rear its head. Or perhaps translators worry about appearing illogical if the obvious (unwritten) parts are left out.

“A Community in the Open” is a case in point. There is an image evoking high modernism in the last line of the three-line first stanza: “the end of a corroded steel framework,” which is contrasted with natural images of chrysanthemums. One might object to the description Takano includes of “Beautiful ladies (who) wave / Their thin-cloth skirts.” The original Japanese simply states thin skirt, not the material. One more nit-pick is a line in the poem “Eternal Twilight.” While it would have sufficed to translate “The bird moves / Gradually up the branch,” it is translated instead as “The bird moves / Gradually up on the branch,” the “on” being an unneeded preposition. Takano, apparently, had his reasons for including it.

The poem “A Night Canal” supplements the original with several superfluous words. The first two lines of the four-stanza poem describe natural aquatic life such as seagulls and fish. The last two lines of the quatrain explain that they “Sometimes spring up painfully from the water / And sink deep back into the water.” In both cases, water isn’t mentioned in the original. The readers should be able to realize the (unwritten) existence of water. Further, the first-person declarative statement “I’m talking about” is affixed twice even though in the original, no “I” appears, and certainly not in that exclamatory mode. Of course, it is always a challenge to translate Japanese poetry into English because of the lack of first-person references. One understands the challenges Nakano faced.

Rather than dwell on these quibbles, the takeaways from this volume are the sharp standout images in poems such as “An Autumn Day” and “An Autumn Torso.” The former describes seeing a bug whose face somehow seems human. The narrator tries to grab it but the insect stings the person’s finger and suddenly takes flight, looking almost like a large dinosaur. The last of three stanzas read

It flew up to the top

Of a nearby tall privet tree

And sang

Sadly with the blood

On its transparent wings

To me what is striking about this slim volume is its highly modernist, nostalgic feel, the sharply defined, startling images and the rhythmic use of language. In addition to these merits, the author’s postscript delves into the poetics and ideas of Basho Matsuo and Nishiwaki Junzaburo. While each of the translations in this volume might not please all critics (an impossible feat), it is very much welcome as a portal to the poetry and poetics of Shiro Murano, who has been largely neglected until now. As a last note, the design of the cover and contents by Jeff Sanner is fresh.

Taylor Mignon is editor emeritus and co-founder of Tokyo Poetry Journal. www.topojo.com.