1: An Interview with Mrs. Koko Kondo, The Tanimoto Peace Foundation

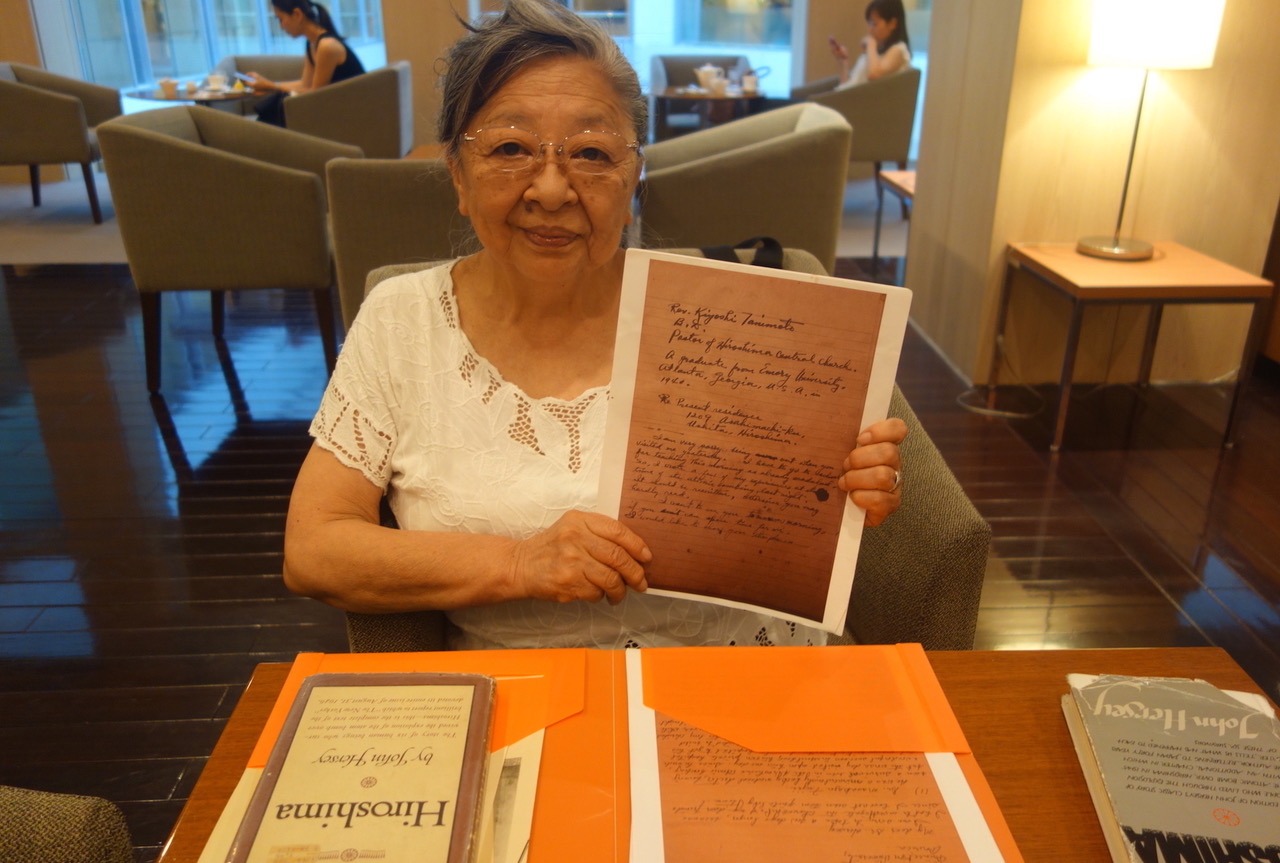

Mrs. Koko Kondo showing the manuscript written by her father,

Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto, that inspired John Hersey’s classic, Hiroshima.

Do you think the Hibakusha are still important?

They are still very important. This is because those individuals of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are the only humans who have ever experienced and survived a nuclear bombing. That is a fact. They are the ones who know. Only they. That’s why they are so important. But now, they are quite elderly and someday they will no longer be able to relate their own experiences. That is another important fact.

The other day some students said to me, “Oh, we’ve heard these same kind of stories before.” And I replied, “Of course. Everybody in Hiroshima and Nagasaki went through them, including me. But each one of them had a different experience and each of us has had a different life. And now all of them feel a need to express that experience to others and to the world. If you don’t listen to them now, you may never be able to hear them again. So that’s why it’s important.”

Finally, some students said, “We agree with you Mrs. Kondo.”

Sometimes I have to hit them in their heads to wake them up.

Some say that there will never be other Hibakusha, because if there are, there will be no one left to listen to them. Do you agree?

Yes, I do. We first generation Hibakusha are very aware of that.

One thing is for sure. We who have experienced the nuclear bombings have tried so hard to relate our experiences for one reason only — none of us can bear the thought of a third one.

That one moment, the moment that the nuclear bomb exploded, you carry that one moment with you for the rest of your life.

I remember near the end of my father’s life, a time when he was becoming quite weak. There was the sound of a clock ticking in the room, gatchi, gatchi, gatchi . . . My father asked, “What is that sound?” He was told it was the clock in the room. And my father replied, “Oh, I hope it’s not the bomb.”

So, you see, he was always thinking about the bomb, from the time of the explosion until nearly the time of his death in 1986, more than 41 years later.

It was the one moment in his life he would always remember.

How about your own memory and thoughts while you were young?

When I was very young, for many years my parents told me, “Koko, you were able to survive. You’re the only baby to survive in our neighborhood. So you must work for peace. You must work for Hiroshima.”

But I told them, “No. Not me.” For a long time, I adamantly refused.

Then finally, when I was forty, it was the time of my father’s last sermon at his church. Of course, at first he read and talked about the Bible, but then he started to talk about why he was so involved with the Hiroshima survivors, the Hibakusha. And for the first time he expressed publicly what he felt on August 6th of 1945. I had never heard him talk about it before, his own experience of that day. The three of us, who were there, simply never talked about it with each other. Most Hibakusha families, I believe, were the same.

Well, as my father related that day, when he saw the flash over the city from the mountain and then fire everywhere, the first thing that came into his mind was, “what’s happened to my daughter, what’s happened to my wife, what’s happened to my church members, what’s happened to my neighbors.” And so he rushed down into the city. As he ran past the dead and the dying, the countless victims, so many of them were asking for his help. “Help! Help!” so many cried. Being a minister, of course he wanted to help. But he told us on that day that the first thing that came into his mind was, “What has happened to my family, my daughter, my wife?”

Then he told us that he suddenly asked himself, “What kind of a self-centered man am I? I’m only thinking about my own, not all of these that I’m passing by.” Being a minister of the church, he felt a strong self-resentment growing inside, and along with that a feeling that his thoughts were purely egoistic. He then told the group listening to him, including me, that his deep self-resentment made him become an activist in the Hibakusha peace movement.

And just then, as my father spoke, I realized I had been doing the same thing. Thinking of myself rather than of others. I believe it was a day that changed my life. I too would begin to speak for the Hibakusha, to express their messages of peace, of humble acceptance without blame, and of course of warning. It was a day when my life changed and my independent peace activism began.

That’s very fine. Can you please give me an example of Reverend Tanimoto’s missions of telling the American people about the atomic bombings?

Okay, I have it written here. These are some details from my father’s records from his first trip to the U.S. after the war. He kept records of everything. Please remember this is just one time of many such trips.

From September 1948 until January 1950, for about 15 months, he went to 31 states, 256 cities, 472 churches, schools and other locations, and gave 582 lectures to which about 160,000 people listened, while he traveled over 65,000 miles. He wrote each detail of those many trips, so his records are complete.

Over the years, I followed his lead, constantly traveling and lecturing, but I never counted my trips in such detail as he did during that time.

Then one could easily say that your father was one of if not the initiator of the Hibakusha Peace Movement and was succeeded by his daughter.

Perhaps, but I wouldn’t want to express that myself. We simply have done and continue to do what we can.

Do you have any other memories of your early years, experiences that may have affected you in some way?

When I was a small child, maybe three or four years old, young teen-age girls used to come to my father’s church and they were so nice to me. I remember they would sometimes gently comb my hair. But I could never look at their faces because they were so deformed. I just wanted to look at the combs they were using, nothing else. But, of course, I saw their hands and on many of them the skin had melted and the bones were deformed.

And when I shyly and slowly looked up, I saw that their faces also had been terribly disfigured. But even as a little child, I did not ask those girls, “What happened to your face? What happened to your hands?” I knew it was not the right thing to ask even at that young age. But I saw, and I felt their pain.

I also listened to their talk and as I listened I suddenly realized that they were victims of the atomic bomb. You see, the realization of what had happened was coming to me and then disappearing again when I was so young. People did not talk about it, not even my parents. Everyone was so busy and it was not something to talk about. There was too much to do.

So the memory of those poor young girls stays with me.

You mean, you never talked about the bomb even with your parents?

No, not really. Of course we knew about it, we were deeply aware of it, but we never discussed it in any way. I knew I was a survivor, but I didn’t know how I survived, and I never asked my parents. We all kept these memories deep inside ourselves.

Then, when I was about 40, one day my mother said to me, “I better tell you what happened to us.”

That’s about the same time as your father’s last lecture at the church, isn’t it?

Yes, in perhaps the same year.

Then everything was starting to come together for you including things that had been suppressed by you and your parents.

Yes. What had been abstract or vague was beginning to become clear.

I remember my mother and I sat on the couch and she filled me in on some of the things that were missing from my memories. That was the first time, face to face. Of course, I knew the basics, but this was somewhat different. This was my mother telling me her story. I didn’t ask any questions. I just quietly listened to her talk.

Then for 40 years your family never talked about the bombing openly?

No. Nothing. Never.

Of course we sometimes would talk when we had guests coming from overseas, but that was very different. That was a public talk. It was quite different than family talk, which we did not do until that time when I was 40, both through my father’s speech at the church and my mother’s revealing talk on the couch.

Again, I believe this was common among many Hibakusha families. It was something that we had all experienced at a very deep level. Not something that can be easily talked about, perhaps especially among family members.

Who besides your father has influenced your life’s path?

Yes. That’s a good question, and one that I can easily answer. Whenever I have been asked to give a talk, I have often told my story of Captain Robert Lewis, the co-pilot of the Engola Gay. That was the B-29 that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima.

Of course, as many know, in 1955, my father was a guest on an American television program, This Is Your Life. It was very popular and many famous people, such as actors, artists or musicians, appeared on it. And ten years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, my father was the show’s guest.

The main feature of the show was to tell the story of a man or woman who had contributed their life to making the world a better place, in one way or another. And the way the television host would do this was by suddenly introducing various people connected with the guest’s life, to first surprise the guest and then to talk with him or her on the show about their shared memories.

Aside from my father’s colleagues and friends, including members of one of his former congregations in the U.S., our whole family, my mother, I and my two brothers and sister, were secretly invited and brought all the way from Japan to surprise my father. All the surprise guests were kept in deep secrecy until they would suddenly come onto the stage into the television screens.

One of those guests was Captain Robert Lewis.

I was ten years old at that time and so, of course, I was in a kind of dream, waiting with my mother and brothers and sister to appear with the other guests as a big surprise for my father. And while standing on the back stage with my family I saw three other people at the other end of the stage. I knew two of them were close of my father so I was so happy to see them. But I didn’t know the third person standing next to them.

Since I was a fifth grader at the time and very curious, I asked my mother, “Who is that man over there?” But she wouldn’t answer me. If she didn’t know who he was, she certainly would have answered me by saying something like, “Koko, I’m sorry. I don’t know.” She knew who it was but thought it better to not tell me. She knew her daughter very well.

However, as we waited longer for the program to begin, she eventually decided that she had better tell me before we went in front of the cameras, just in case, as she understood my temper.

So she said, “Koko. That is Captain Robert Lewis, the co-pilot of the Enola Gay.”

Hearing that, I remembered those girls who came to visit me at the church back in those years after the war. They would say, “Koko-chan. Koko-chan.” They were so sweet. They treated me like their own younger sister. And I remember as they talked about the bomb, I began thinking at that very young age, someday I would find the person on that B-29 bomber and when I did I would give him a punch or a bite or a kick.

That’s what I can do and that’s what I will do, I thought.

I knew that if my parents would find out my thoughts, they would give me a long speech about the Bible and why that kind of thinking was wrong. So I never told them. I just kept it deep inside waiting for the time when I could do it. Always thinking, “I’m definitely going to do it.”

So, what happened? Did you kick him, or bite him, or punch him?

Well, I knew I couldn’t do that. That was not the right thing to do at that time, of course. So I just stared at him thinking, “He’s the bad guy. And I’m the hero.”

Right?

Right, of course.

As we waited for our family to go on stage, I did not understand most of the conversation as the guests appeared one by one. However, I did understand when Ralph Edwards, the host of the show, asked Robert Lewis, “How did you feel when you dropped the bomb?”

And Captain Lewis replied that they dropped the bomb at 8:15 am and then quickly flew away due to the danger of the explosion. But the plane soon had to return to see the results of the bombing. Lewis said that he looked down and the city of Hiroshima had completely disappeared. And then he said that he wrote a note to his mother, “My God, what have we done.”

And from his eyes, live on that stage, the tears escaped.

When I saw that, I thought, “He’s not a monster. He’s a human being.”

I looked inside of myself and felt so sorry. I did not know anything about

this man. And I realized that I had so much evil inside myself. And then I suddenly understood that if I hate, I should hate war itself, not this person.

Did you have a chance to talk with Captain Lewis?

Well, after the show we were all still on the stage and I don’t know why I did it but I walked like a shy crab across the stage and touched his hand. That was the moment I wanted to say, “I’m sorry.” But, of course, I could not speak.

Captain Lewis immediately recognized what I was trying to convey and he gently held my hand and turned us both to the audience that was still there. That is one of the most important moments in my life.

Did you ever meet him again?

In my junior year in a U.S. college, about ten years later, I suddenly wanted to see him. I just wanted to say, “Thank you. It’s because of you, sir, that little Koko changed.”

But I couldn’t find him. So I asked my father’s friends to find him and they did. They told me, “I’m sorry, Koko. Robert Lewis is in a hospital. A mental hospital.”

I was a poor student and the U.S. is such a big country, so I didn’t go to visit him. But I really wanted to meet him to express my sincere thoughts, and since I was so busy at school, I didn’t think about him after that.

I came back to Japan and five and a half years passed. Then one day, I opened the newspaper and found out that he had passed away. I felt deep regret that we had not met again.

And a few years following that I saw an article where a psychotherapist

was showing a sculpture that Robert Lewis had made while at the mental hospital. It was of a mushroom cloud with one tear.

That sculpture is somewhere in this world and someday I hope that I will be able to see it. So for Captain Lewis, I knew that he also suffered and I learned that in war both sides suffer. And now, whenever I meet with young people from East and Southeast Asia, I first have to say, “I’m sorry for what Japan did.”

In Hiroshima City there is a cenotaph dedicated to the victims of the nuclear bombing. On that cenotaph there is an inscription, “Rest in peace, we shall never repeat our mistake.” However, Hiroshima City translated that in English to, “Rest in peace. We shall never repeat our evil.”

But to me, evil is too strong a word. The word in Japanese is “ayamachi” which we usually translate as “mistake”. Although others may think that mistake is too light, I feel that the word evil is far too strong.

Human beings are not evil, what we do certainly may be, but it is not who we are.

Don’t you agree?

Yes. Thank you very much for this interview, Koko.

You’re very welcome.

_______________

Interviewer’s note: It is important to point out the circumstances behind the documents that Mrs. Koko Kondo shows in the image taken at the beginning of this interview. The pages of the document that Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto wrote are copies of the actually documents kept in the Yale University Library. Cannon Hersey, John Hersey’s grandson who had visited the library, sent the copies to Mrs. Koko Kondo in 2016.

When John Hersey first went to Hiroshima City in January of 1946, just five months after the bombing, he had already heard about Reverend Tanimoto’s work and knew that he would be an important individual to call upon during his stay there. He visited the Tanimoto family’s dwelling twice, but Mr. Tanimoto was not at home since he was constantly working to help others in the still devastated community.

When Mr. Tanimoto returned and found out that Mr. Hersey had called on him to ask about his experiences on the day of the bombing, he was very troubled that he may have missed an opportunity to express what he knew and that Mr. Hersey might never come again, that he stayed up all night and wrote many pages of the long letter. As can be seen above, he didn’t care about scribbling out mistakes. There simply wasn’t enough time. He felt he had to finish by morning when John Hersey said he would visit again.

Having had a look at the documents before this interview, it is clear to this writer that Mr. Tanimoto had presented Mr. Hersey with inspiring words that he later transformed into his classic of peace journalism, Hiroshima.

With that fact in mind, and with all of what has been read about Mr. Tanimoto through Hiroshima as it appeared in full in The New Yorker magazine in 1946 and in a sequel, entitled Hiroshima: The Aftermath. published in 1985, it is obvious that Reverend Kiyoshi Tanimoto was the incipient and most insistent voice of the Hibakusha Peace Movement.

Our world owes both of these men a great debt along with all the Hibakusha who have struggled for these many years to express the inexpressible.

Perhaps it is they who have kept us safe until now.

What has kept the world safe from the bomb since 1945 has not been deterrence, in the sense of fear of specific weapons, so much as it’s been memory. The memory of what happened at Hiroshima (and Nagasaki). ~~ John Hersey

(The Interview was conducted in Kobe, Japan on July 27, 2018)

Robert Kowalczyk was professor and chair (retired) of the Department of Intercultural Studies at Kindai University, Osaka, Japan. He has taught, written on and coordinated a wide variety of projects in the intercultural field, and is currently the international coordinator of Peace Mask Project. Robert has also worked in cultural documentary photography and has portfolios of images from Korea, Japan, China, Russia and other countries. He has been a frequent contributor to Kyoto Journal and is a member of the Transcend Peace Network.

This article was originally published on Transcend Media Service on the 6th of August.

https://www.transcend.org/tms/2018/08/a-distant-flickering-light-the-hibakusha-peace-movement-part-1/

Advertise in Kyoto Journal! See our print, digital and online advertising rates.

Recipient of the Commissioner’s Award of the Japanese Cultural Affairs Agency 2013