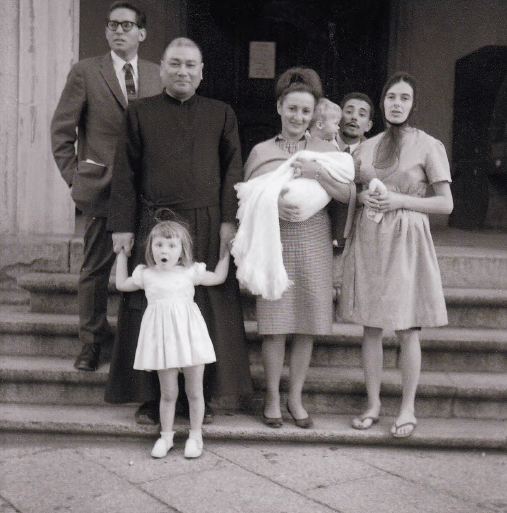

The photographs in the old wire-bound album that record the occasion leave a lot to be desired when it comes to print quality. The small gathering on the steps outside the entrance to St Francis Xavier church on Sanjo in Kyoto, in the autumn of 1965, was celebrating the baptism of our newborn daughter; and the people were from Kyoto, Chicago, Beirut, Rome and Sydney. The baby’s older siblings, a boy and a girl, were present and getting attention from Fr. Maruyama. We took the new baby girl home to Minami-Hiyoshi-cho and a bamboo basket a local craftsman had specially made for her.

That little group of foreigners on the steps of the Sanjo church were living among people in whom the memory of the fire bombings of the tatami, tile and timber cities was embedded. And with the shocking memories of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In that time we lived with the threat that the Cold War might become a thermonuclear holocaust. And our family baptism had taken place in the twentieth anniversary year of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

On 23 November 1945, when he spoke at the Requiem Mass for the dead, near the ruins of the Nagasaki cathedral, Dr. Takashi Nagai used the word ‘holocaust’ (hansai) to describe what had befallen his city. But any survey taken in the United States or Australia in those years would have supported the use of atomic weapons. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not on the travel agendas of Australians. There was remarkable lack of curiosity; and as for compassion…

Big obstacles were in the way of any attempt to change perceptions about these terrible weapons. As an artist, it seemed to me that the story of the afflicted cities did not lend itself to Abstract Expression or Colour Field painting. In the visual arts of those decades of ‘Cold War Modern,’ the human image all but disappeared; imagery had to sit comfortably in board rooms. “Artists and designers played a central role in the Cold War battle of images. Their work was conscripted for propaganda and their actions and opinions prized.”

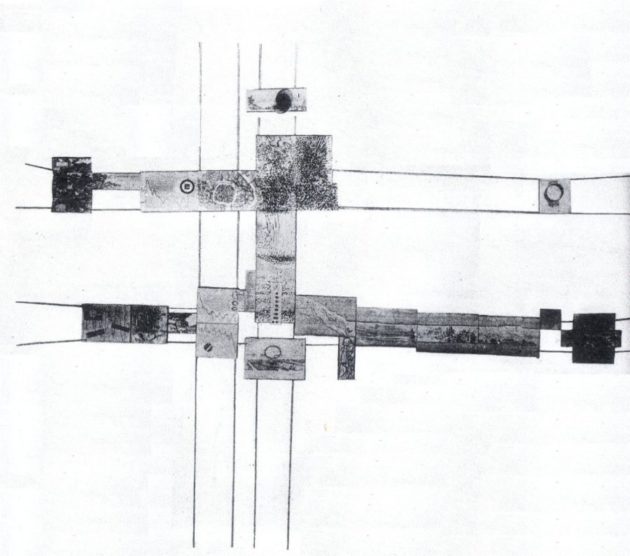

In 1966, the year after the baptism, we had taken a week-long visit to Hiroshima. On our return to Australia, we turned our minds to the problem of drawing attention to this terrifying meeting of East and West. We made and exhibited in 1970 Reading for August 6.

Among the first published accounts of the nuclear attacks was that of We of Nagasaki: Eight survivors in an atomic wasteland by Takashi Nagai. This became available in English in 1951 and went through numerous editions. But nothing else of Nagai’s was available in English until 1984 when his first work, The Bells of Nagasaki, originally published in 1949, was finally translated. (It was published in Italian in 1952). The English-speaking world had had to wait 35 years for the writings of the only trained Japanese scientific observer of the effects of atomic devastation.

We were members of a research group with a great interest in nuclear physics and totally devoted to this branch of science—and ironically we ourselves had become victims of the atom bomb which was the very core of the theory we were studying. Here we lay, helpless in a dugout.

I am at a loss to understand why The Bells of Nagasaki, an immensely significant, successful and popular work in Japan, had had to wait so long for translation.

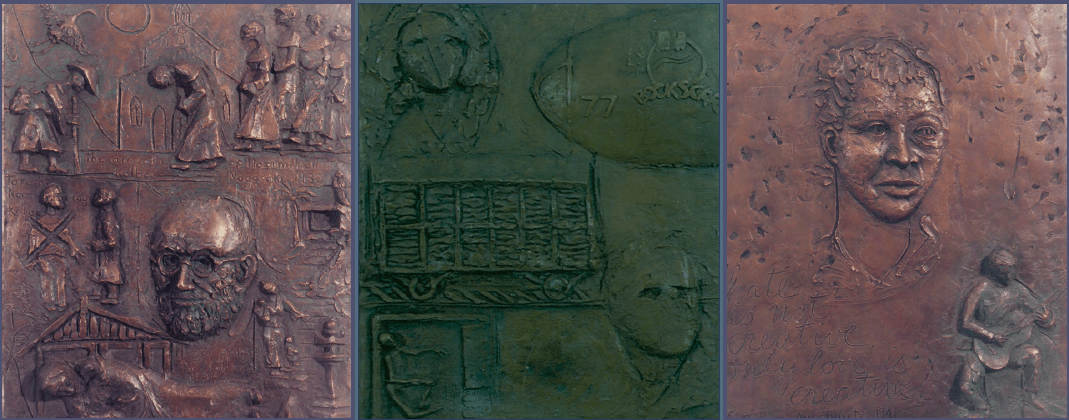

Some years after making Reading for August 6, after the publication of The Bells of Nagasaki, having become aware of the fact that, on August 9 1945, the crew of “Bocks Car” used the steeple of St Mary’s Urakami Cathedral, the largest Christian church in East Asia, for targeting purposes; and fascinated by Dr. Nagai’s meeting and friendship in the 1930s with Fr. Maximilian Kolbe (who was later to die in Auschwitz), I made three bronze reliefs inspired by their story.

Any old day will do for a pilgrimage. In 2009, I left Australia’s inland winter and spent a week in Nagasaki. On my first day in the city I caught the number 3 tram up to Urakami and walked up to Nyoko-do (“thy neighbour as thyself” house.) I sat in the sun on the seat outside the tiny, two-mat traditional home—classic Japanese architecture—that Dr. Nagai moved into in the spring of 1947 when he became bedridden and could no longer function as a doctor.

Dr. Nagai was a unique witness and in Nyokodo he wrote, painted, welcomed visitors, played with his children, prayed. The house became an improbable center of literary activity. Before his death in 1951, Nagai had written 12 books , 11 in that little room. (In 2008, a third Nagai book, Leaving My Beloved Children Behind, appeared in English.)

The same censorship that seems to have operated with the written word in relation to the use of nuclear weapons affected the publication of visual images. When, on 1 June 2014, the British Daily Mail published a news item about a photo album about to go on sale in New York, perhaps it also provided an explanation of the censorship. Among the album’s photos were 24 taken by Yosuke Yamahata, a Japanese photographer, one day after the bombing of Nagasaki.

The album contains some of Yamahata’s most famous images but there are others in the set that have never been seen before… These photographs started off life as propaganda against the Americans, who wanted very much to cover up what they had just done.

Censorship was high and so the photos of the destruction were kept under shop counters and handed out surreptitiously. At some point it seems [a] military policeman confiscated the photos from a Japanese citizen in Osaka and put them in his album with no knowledge of their importance…

The woman in the photo [above] was Tanaka Kio who… died of pneumonia on Dec. 9, 2006. She was 91. The child in the photo was her 4-month-old second son who died 11 days later. She also lost her eldest son. She and her two sons were in the rice paddy about 2 km from the epicenter.

… These photos serve as a reminder of the power we hold that keeps the peace. Today’s nuclear bombs are 100 times [the] ferocity of those that fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Right next to Nagai’s last home is a small, very moving museum which leads one back into that time. There one finds all Nagai’s books and articles and the story, through relics, of the life lived by Dr Nagai and his wife, Midori. She was a descendant of the hidden Christians, who survived persecution and after 200 years revealed themselves to the French missionary, Fr. Bernard Petitjean, on 17 March, 1865.

Seventy years on from the bombing, Nagasaki’s Urakami cathedral has long been rebuilt. Across from the church are the current Archdiocesan offices. I decided to visit and was invited in and met and had tea with Archbishop Joseph Mitsuaki Takami who was in utero when the bomb exploded and who has dedicated his life to the abolition of nuclear weapons. “We humans produce weapons and we humans can and must do away with them.”

At that time, Barack Obama had just been elected President of the USA, and local high school students in were collecting signatures on a petition to invite him to visit the museum at Nagasaki.

In 2002, The Bells of Nagasaki was translated into Bengali by Ahbubur Rahman, a lawyer. The translation was intended for high schools, universities and libraries in Bangladesh. Rahman’s is just one of the innumerable small steps that need to be taken.

The possession of nuclear weapons by any state must be genocidal in implication. As long as nuclear weapons continue to exist in nation state stockpiles, there is no security and the threat of their use against humanity by rogue ideologies and murderous heresies continues to exist. Regions with states that have not signed the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty must face this reality.

We have to take to heart the understanding embedded in Nyoko-Do.

It was Dr Nagai’s hope that his city and his people would be the last to experience destruction and its traumatic aftermath by a nuclear weapon. So far—so good.

I caught the tram back to town, enjoying the ride and the way the driver sang the stops’ names. I had been advised not to miss out on Nagasaki noodles (udon.) Very famous. Highly recommended.

Bill Clements, born 1933 in Melbourne, Australia, is a practicing and exhibiting sculptor and printmaker. From 1964-67 he studied in Japan on a Monbusho scholarship and Saionji fellowship. www.williamclements.com.au

All images above by Bill Clements, except for Nyoko-do, the house of Nagai Takashi which is by Phillip Marshall and sourced from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Nyoko-do_Hermitage,_Nagasaki.jpg