[D]owntown Seoul has more protest spots than coffeehouses. Protesters of many persuasions have taken up a permanent, rotating residency in front of the Blue House, South Korea’s presidential mansion, while the American embassy is never without riot police. For most of the country’s history, demonstrations have been put down with an iron fist. In the 1960s, widespread protest won a three-year respite from dictatorship. Though short-lived, it piqued the hunger for democratic reform. Dissent then burned underground for two decades. Ultimately, the military regime could not contain it. In 1985, the struggle was reignited en masse, and a two-year protest campaign brought down the government. No velvet revolution here, but a series of powerful, sustained confrontations, culminating in a radical rewriting of the social contract. Its provisions are still being negotiated, in parliament and on the street.

Demonstrations, accepted and widespread as they are, are now but one facet of public debate. The traditional protest repertoire of marches, sit-ins, stones and Molotov cocktails is evolving. Some of the new techniques remain confrontational, even violent. Others rely on technology, subtlety, inner strength and community.

Lee Won Jae of Cultural Action sees it this way: “The patterns and genres are set, but there is a big demand for innovation, mostly from the side of the peace and ecology movements. Even the labor unions see that aggressive mass rallies have lost some impact. There’s a shift to non-violent protests, but the repertoire is limited. People are hungry for new ways.” Says one Green, “We don’t like to go out and shout.” Illegal hip-hop concerts are more her idea of a good protest. A labor media activist reflects, “We separate action and daily life…go to a rally, then home. We have to integrate struggle into our everyday lives.”

Here are some methods of protest now widely used:

Candlelight Vigil (Chopul)

Widespread since the 2002 Yang-ju incident in Kyoung-gi Province. A U.S. military vehicle killed two school girls, but the American military court exonerated the driver, bringing discontent with U.S. military presence to a boil. Nationwide candlelight vigils ensued, quickly becoming a dominant protest genre. Not everyone subscribes. One labor movement organizer explains, “There are many meanings attached to candles: grief, peace, remembrance… Chopul does not emphasize agency, but victimization.” Still, this method was used to bring the more progressive Roh Myunhun to the presidency, and later to successfully protest his impeachment proceedings.

Lie-in

The classic sit-down demo spawned the lie-in. One staged at a Daewoo plant in 2001 by men naked to the waist (to show that they were unarmed) ended with eleven protesters beaten to the point of becoming invalids, and hundreds of others injured. As one witness recalls, “Riot police had sharpened the edges of their shields on the asphalt, then used them to break ribs and puncture people’s lungs. We found ourselves wishing for tear gas… ” In the three-month struggle, protesters also used Molotov cocktails, painted their bodies with “wishes to be let into the union office,” broke into the former CEO’s French villa, brought forklifts and their families to marches, and set cars on fire.

See the 2001 Daewoo struggle, documented by organizers KCTU (Korean Coalition of Trade Unions) at: http://dwtubon.nodong.net/english/

Follow the Mimes

The cultural committees of labor unions keep rallies lively and cheer striking workers, offering plays and organizing screenings. In marches, black-dressed “dancing agitators” lead crowds in movements. The set sequences may include pantomime (putting on a strike vest), gestures (shaking a fist), and moves from dance and martial arts.

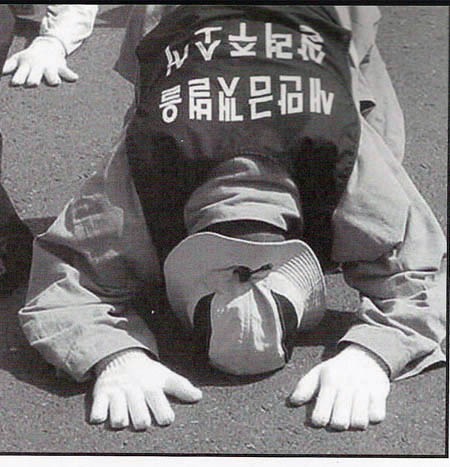

Three Steps, One Bow (Sambo Ilbae)

Simple, but powerful: Walk three steps, prostrate, rise, repeat…. for several (or several hundred) kilometers. From the Chogye order of Buddhism, whose aspiring monks and nuns perform it to shed the “three poisons” — greed, anger and delusion. Pioneered as a protest technique by Abbot Sugyeong of Sudeoksa temple, one of Korea’s oldest, it became the signature action against the Mount Bukhan tunnel and the Mount Jiri reservoir projects. In a 2003 protest against the Saemangeun Land Reclamation Project, four spiritual leaders covered the 305 km from Puan to Seoul in 65 days. Thousands organized by Green Korea and others joined for stretches and support events, and Buddhist groups organized solidarity sambo ilbae walks internationally.

Band-in-a-truck

A truck pulls up to a crowded curb, opens one side, the lights go up, and bam: a wall of sound. Bands, some famous, some aiming to be, jam on well-known protest tunes and songs written for the occasion. “The band truck has lots of advantages: you can put up a fancy stage for an illegal concert, pack up quickly and be gone before the police get you,” says an activist from Cultural Action (credited with pioneering the technique around 2000). In an alternate version, the “peace caravan” moves while people walk and dance alongside.

[See bands and songs at People’s Song http://plsong.org]

Protest Fashion

The basics were: a vest (like a factory workers uniform), headband and body-banner, the color and slogans depending on union affiliation. Tear gas is now banned, but surgical masks help against burning tire fumes, fire extinguisher foam… and provide another surface for slogans. As protest culture evolves, so does fashion. The fight for maternity leave featured members of the Korean Women’s Trade Union marching in dresses “pregnant” with pillows. “If you want to freak out your employer, try wearing a pink strike vest to work!” said one organizer. On eco and peace marches, animal costumes, traditional pilgrims’ dress and nuke suits are increasingly popular.

Caskets

A popular prop in marches of the 1980s, caskets are carried gleefully with captions such as “World Bank,” or mournfully with ones like “Democracy.” Says Choe Seijin, of KCTU (Korean Confederation of Trade Unions), “Company managers in Hong Kong and Taiwan hate it when their workers appear with a casket — they tend to be superstitious. In Korea, it doesn’t scare anyone, it’s just a symbol.”

Media and Communication Technology

IT has been at the core of Korea’s economic policy since the 1980s. Ambitious projects of government and chaebol (conglomerates) to wire the country and build a tech-savvy workforce have had unintended side effects: activists have appropriated the technologies for their movements. Broadband, public wireless Internet access, i-mode cell phones, cheap video gear, a widespread tech know-how have been a bane to the targets of protest. Activists have at once become more agile, elusive, focused and effective. They have created independent video distribution networks, open-publishing online newspapers/bulletin boards, publicly funded centers for media activist training and policy — a whole sphere of communication almost beyond the reach of state and business. At Mayday demos or November rallies, video cameras are connected to live netcasting equipment.

South Korea is the only nation whose president was elected and kept in office largely due to an alternative online newspaper. President Roh gave his first interview not to the main media corporations, but to OhmyNews (motto, “Every citizen is a reporter”).

A video taken by a participant in the bloody Daewoo clashes of 2001 was widely circulated on the net. It convinced even the president that in fact the police did instigate the violence, in spite of their claims to the contrary. “Since then, every rally has become a kind of media war — it’s the police videos against the protesters’ videos…Everybody comes armed with cameras,” says a KCTU info technology staff.

OhmyNews International http://english.ohmynews.com/

(Content originally written in English) Recommended: Howard Rheingold’s Column; signing up to be a citizen reporter.

Jinbonet Korean Progressive Network http://www.jinbo.net/ (Korean)

Hunger strike

Even conservative politicians have used it (Choe Byung-yul of the Grand National Party in 2003, to force President Roh Myun-hee to allow investigation into his campaign funds), but usually this is a tool of the politically weak and spiritually strong: Jiyul Sunim, a Buddhist nun in her late forties, fasted a combined 200 days on water, salt and occasional tea (four fasts, the latest of which ended in February 2005 on the 100th day) to hold Roh to his 2002 election promise to halt and re-assess a controversial tunnel project. Part of a mega-project of high speed train lines, the track between Seoul and Busan was planned to run through Mt. Cheonseong, where her nunnery is located.

Fasting is not the only means of resistance she has used in this fight. In 2003, she prostrated herself 3,000 times a day for 43 days in front of Busan’s City Hall. She was also part of a class action suit on behalf of the clawed salamander (Hynobius leechi), as a representative for the 30 rare species on the mountain endangered by the project” A total of 175,000 people signed a supporting petition, yet a court approved the project. Determined to give her life for her fellow creatures if need be, Jiyul set out on her fourth fast. It was accompanied by candlelight vigils, marathon prayers, the making of prayer quilts and paper salamanders and solidarity fasts across the country, as well as fierce public controversies over the ethical and long-term political implications. Her comment: “People are concerned about my health, I wish they’d care more about the mountain.” She took up food again after prime minister Lee Hae-chan agreed to halt the blasting and conduct a re-assessment together with citizens’ groups. Her protest also prompted a bipartisan parliamentary committee to call for an end to the “devil-may-care way of thinking” that dominates government development policy.

More on Jiyul http://ns1.greenkorea.org/english/

Jungto Society — Buddhist Academy for Ecological Awakening http://www.jungto.org

Protest Suicide

Political suicide, though a small percentage of the yearly total, has a long tradition in South Korea. In 1970, Jan Te-Il burned himself publicly with the labor law in his hand, shouting “enforce the labor law!” He became a heroic figure, drawing attention to the plight of the workers paying a high price for economic progress. The protests of the late ‘80s were accompanied and fired by a series of suicides. In 1991, police killings of two students caused a new wave of demonstrations and suicides by students, activists and workers. Recent years have seen protest suicides by migrant workers (to resist deportation), “irregular workers” (temp workers who have no protection by labor law) and farmers desperate to stop trade liberalization. Sadly, this technique has at times been quite effective, not always for a concrete policy change, but to call attention to the seriousness of an issue. The suicide of a farming movement leader, Lee Kyoung-Hae, at the 2003 WTO protests in Cancun drew the kind of worldwide attention that his hunger strike at WTO headquarters earlier that year had failed to get. The Hanjin Shipbuilding Company in 2004 regularized all its “irregular workers” after the second suicide by one of its shipbuilders. A man had hung himself from his crane, leaving a suicide note saying being an irregular worker was “a frightening thing.”

Movement organizers have been suspected of encouraging would-be martyrs. In 1991, the government used a wave of suicides as a pretext to hunt down dissident leaders and try them for assisting suicide (Source: Human Rights Watch). In reality, most protest suicides appear to be public acts of personal despair in the face of overwhelming political problems, a last resort for speaking out when your voice has gone unheard. “Some of these people have been inspiring and valuable leaders, often good friends…. We discourage protest suicide and give guards to people who seem to have suicide plans,” said a union organizer. Another labor activist said, “We should try to prevent it, but if it happens, we have to respect it.”

Gabi Hadl was formerly KJ’s Circulation manager and Intern coordinator, now coordinates the Buy Nothing Day Japan Network.