The second time I took on the village head role, seven villagers died in one year and my goals as village head changed dramatically. How could we maintain something resembling the status quo? How could we come to terms with the rapid decline in our numbers? How could we find happiness in our simple, daily lives? What could we do to stop or delay the disappearance of the village itself?

The villagers’ answer to that final question caught me off guard and taught me a lot. In meeting after village meeting, their answer was the same. “Do nothing.” When I brought up the possibility of renting out the village’s vacant homes, the villagers were concerned about noise late at night and the arrival of residents who wouldn’t actively participate in village life. At first, I was frustrated that they were not taking action to save the village. In time, though, I came to see the wisdom in wanting to hold onto what they had, to protect their values, their community, their lives. An infusion of outsiders might delay the village’s disappearance, but to what end? What I had initially seen as a passive response was, in fact, a pointed, active decision to hold onto what they had.

I came to think of the death of a village as a natural turn of events, a natural stage in its evolution. I came to see it much like the death of an individual person. Why sacrifice quality of life in the name of a longer life? Why make use of life support systems that the villagers didn’t want and hadn’t asked for?

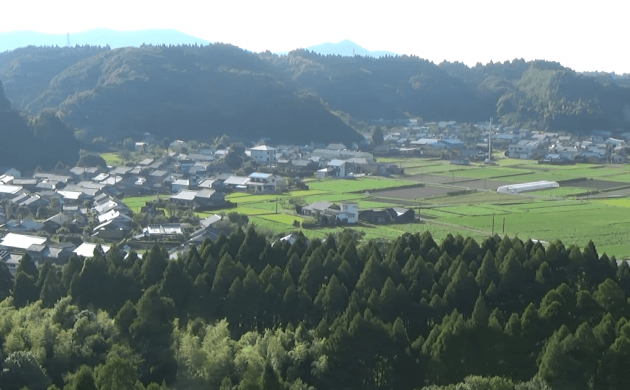

On later moving to a larger nearby community, Jeff realized that while apparently thriving, his new home, Takata, was also threatened by eventual, inexorable decline.

A few years into my new life in Takata, I obtained data from the local government about the age, gender and size of every household in Takata. Using gender and age-specific longevity tables for Kagoshima Prefecture, I calculated population loss over the next 30 years.

I was stunned by what I found. Because 41% of the households had only one occupant and a significant percentage of these single occupants were elderly, with each death another house became vacant. Conservative estimates revealed a population loss of 59% over the next 30 years, and 69% of the current homes becoming vacant—and these estimates didn’t take outmigration and long-term hospitalization into account. A population of 1407 in 2017 would drop to 581 by 2047. And when I calculated the change in the number of occupied households, I found that 265 homes will be vacated in the first decade, 117 in the second decade and 78 in the third, for a total of 460 vacant homes.

Takata will continue to be confronted by this demographic disaster until the community either comes up with a revolutionary plan or disappears altogether. The following are just a few of the additional factors contributing to this crisis:

In order to address this crisis, the community as a whole must reach a consensus regarding a course of action and commit time and money to it.

Survival Strategy

Having caught a glimpse of Takata’s future, I decided to take action. I set out to identify already vacant homes, to find, communicate with and reach an understanding with their landlords, to prepare vacant homes for re-use, and to find individuals or families who were interested in living in Takata. An initial search revealed the existence of nearly 100 vacant homes, in various stages of attrition, located in central Takata.

I then decided to pursue homes that 1) appeared to be in fairly good condition (structurally sound and not in need of a new roof), and 2) were situated such that they were a comfortable distance from their immediate neighbors. In particular, I looked for homes that enjoyed some distance from the home directly in front. As neighbors in the past were often relatives, homes tend to be located in closer proximity than newly arrived residents would find comfortable.

I also addressed a meeting of the heads of Takata’s sixteen communities and after presenting data forecasting future depopulation and vacancies in each of Takata’s eleven inner and five outer communities, I asked them to help identify homes that might be suitable for rental. I didn’t ask them to contact homeowners, but simply to share any information they might have with me. Unfortunately, only two of the sixteen community leaders responded. A vacant home introduced by one of them is described in Vacant Home #6 below. As described below, I pursued seven vacant homes during the course of the 2017 calendar year.

Vacant Home #1: The Family Altar Craftsman’s Home

This large home with an adjoining area for livestock, a chicken coop, a separate work area and an extensive rock garden was most recently lived in by a couple who made metal fittings and decorations for Buddhist family altars. They had worked in a separate, adjacent structure comparable in size to the house until their deaths in 2009 and 2011. The couple died fairly young—while still in their late 60s—and were survived by two sons, the elder living in Tokyo and the younger in Kagoshima City. I learned of the potential availability of this home from Mitsuo Arimura, a retired cattle farmer and leader in the community. I had the opportunity to meet the elder son when he returned home for New Years and we spent several hours together looking at the home and discussing its potential. As his parents had died young and he had worked with them for a number of years, he had not been emotionally prepared to rent the home out until recently and my interest in the home helped him to see the home in a more positive light.

I introduced him to Koyo Sato, a 29-year-old artist who was hoping to find a place to live in Takata and they reached a tentative agreement for Mr. Sato to move in sometime in the upcoming months. After the elder son had returned to Tokyo, twelve university students and I spent an afternoon cleaning out the work space. Mr. Arimura borrowed a truck with a crane assembly and we also removed a large rice-drying machine. The second son had agreed to remove the family Buddhist altar from the home and, in keeping with his request, an official rental contract had been prepared.

However, when Mr. Arimura, Mr. Sato and I visited the home the following week and happened to meet the second son and his wife there, we were told that the home was no longer available for rent. It remains unclear why the initial decision was reversed but most likely this change reflects a rift between the two brothers. I had mistakenly assumed that the elder brother had the authority to approve the rental of the house as would traditionally be the case in a Japanese family. Apparently, the younger brother, a medical doctor, and his wife, were not ready to give him that authority and not prepared to rent out the house. One year has passed and the home remains vacant.

Vacant Home #2: The Tobacco Storehouse Home

Located at the upper end of Takata, this moderately-sized home has a rock garden and small vegetable garden in the back and a separate storehouse originally for the hanging and drying of tobacco. The house was rebuilt in 1962, shortly after a major fire destroyed most of the homes in the area. Only the storehouse pre-dates the fire. The home was originally occupied by the Uchiharas. The husband—a woodsman and farmer —died in the late 1960s and thereafter the home was occupied solely by his widowed wife until she moved into a long-term care facility in 2015.

When it became clear that their mother would not be able to return to her home, her two surviving daughters approached Kazuto Kawahara, a neighbor and the owner of a local construction company, for his advice. He suggested they could sell the home and might be able to find a buyer in the range of $20,000 or they could rent it for $200-250. By chance, later that same week, I asked Mr. Kawahara if he was aware of any vacant homes that might be available for rent. I asked in keeping with my general search for vacant homes and with a specific interest in finding a home for Mr. Sato.

In February, the daughters, Mr. Sato, Mr. Kawahara and I met at the home. At this meeting, the daughters agreed to rent the home to Mr. Sato for $250 per month. The decision was made to leave the family’s Buddhist altar in the house, covered by a simple curtain. Mr. Sato has been living in the home for almost one year now and is an active member of the community.

Vacant Home #3: The Construction Company Employee’s Home

Located near a large shrine on the eastern end of Takata, this large home was first built in the 1950s and then rebuilt when its owners—the Ohtanis—retired and returned to Takata in the 1980s. The couple lived together in the home for some twenty years until the husband’s death. Thereafter the wife remained alone in the home for ten more years until 2012 when she moved into a facility for the elderly in Tokyo to be near her three children.

This home is in excellent condition. It has a tea ceremony room with a separate entrance, a garage and a large potential office space located several steps up from a spacious kitchen and dining area. Located a safe distance above a fairly large river, the house comes with several additional plots of land planted with various flowering and fruit-bearing trees.

Shoichi Ohtani, the second son, whose area of expertise is the management of mainframe computers used in semiconductor chip manufacturing plants, considered moving into the family home, but was unable to find work in the Kagoshima area. He agreed to share any new information with regard to the family’s intentions for the home and I said I would keep him informed of any new developments regarding potential renters.

Vacant Home #4: The School Teacher’s Home

Located along a waterway at the upper end of Takata, this medium-sized farmhouse with an adjoining area for livestock was built in 1962 with recycled materials from two other homes, one of which stood in the same location and was burned down in a major fire that destroyed 52 homes in this part of Takata. The current owner, their son and his wife, are retired school teachers. They live in Kagoshima City and visit the home on weekends a few times a month to tend to the yard and air out the home.

This home was “found” by Koyo Sato, the new resident in Vacant Home #2, and introduced to me. When I and others showed an interest in the home, the owners appear to have found a new appreciation of the home as well so while they were initially receptive to the idea of renting it out, they have decided not to rent it for the time being. This home may become an option sometime in the future and I remain in contact with the owners.

Vacant Home #5: The Kirin Beer Employee’s Home

This is a small farmhouse with an adjoining two-story barn, a medium-sized garden plot in the back and an electric-powered well with potable water. The first floor of the barn, originally for livestock, can now be used to park a car and the upstairs storage area can potentially be converted into an office space or bedroom. The home was built in 1961 and likely with the help of a new tile roof it survived a major fire that ravaged the thatched roof homes in the immediate vicinity the following year.

The home’s original owners were Seiji and Fuji Haraguchi. Seiji had worked for Kirin Beer in the Kansai area and it was with money saved from this work that he paid for its construction. Seiji died in 1988 and Fuji in 2000. Their son Hiroshi, a retired carpenter living in Kagoshima City with his wife Etsuko, visited the home regularly until back problems made it increasingly difficult for him to walk or drive. As a consequence, he and his wife rely on their son—who is quite busy—to drive them to Takata a few times a year.

With permission from the Haraguchis, I worked with a group of college students to clean out the house on four different occasions. Borrowing a large truck from Mr. Arimura, we made numerous trips to the local dump to dispose of old bedding, clothing and other household items. The cleaning stage complete, the house is in excellent condition.

The owner has given me a copy of the keys to the house and I am currently responsible for the maintenance of the house and yard. The owner is open to the rental or sale of the house.

Vacant Home #6: The Long-Term Care Woman’s Home

This small farmhouse with an adjoining area for livestock and a small garden plot in front was introduced to me by a community leader who is currently looking after the home in question because its owner is living in a long-term care facility with no hope of returning to her home. The community leader was apparently told that she could do with the home as she saw fit. When I was given an opportunity to look inside, I found the home full of its owner’s possessions and in fairly poor condition. It appeared, however, that with the removal of a few flimsy walls and a thorough cleaning, the space could potentially be transformed into a small but comfortable accommodation. When I made this suggestion to the community leader and she passed it on to the homeowner, the homeowner said she was not prepared to let go of her home.

As I am presently unable to communicate directly with the homeowner, I have not pursued this home further.

Vacant Home #7: The Stone Cutter’s Home

A medium-sized farmhouse in one of the most populated areas of central Takata with an adjoining area for livestock and two sizeable sheds originally used for food preparation and for bathing. The house was first built some 130 years ago and has been vacant since 1992. The family’s youngest and only surviving daughter has visited the home on occasion to clean and air it out during the time since. However, with an increasing need to care for her sick husband, her visits have become less frequent and she has relied on a childhood friend next door to look after the house in her absence, putting up storm windows prior to typhoons and such.

The home is in a state of disrepair and requires work on the bathroom wall, the kitchen counter, and the floorboards in several rooms. Roof work may be necessary as well and neighbors have suggested the potential presence of termites. As the two sheds in front of the home were in a dilapidated condition and were limiting the view from the main house, I decided—with the landlady’s permission—to tear them down. We tore down the sheds using heavy machinery and with the help of several men from the community on one day and cleaned out the house on another. Unfortunately, as the house got cleaner its state of disrepair became more evident and it may be too costly to pursue further.

Reflections

I have learned a lot over the past year. I’ve found that time spent listening to the homeowners and encouraging them to share their feelings about their homes has been productive and has helped us to have meaningful communication thereafter. My efforts to communicate with the landlords and to establish rapport has generally been rewarded with trust and cooperation. I have been careful not to rush this process, thereby giving the landlord time to consider their options and to discuss them with other family members. It can be said that this aspect of the vacant home search process is closer to counseling than to sales.

Lacking any experience as a real estate agent, I would have benefited from a more careful assessment of a home’s potential and of the cost of renovation. In the case of Vacant Home #7, smitten by the location (in central Takata) and by the open southward facing plot of land on which the house is situated, I did not pay proper attention to the condition of the house itself and acted prematurely in making the decision to clean the house and to clear the land around it. A more careful look at the house with the assistance of construction, pest control and other experts would likely have led to the decision not to pursue the house in question in keeping with potential problems with the roof and the likelihood of extensive termite infestation.

During the first year of pointedly working to re-occupy Takata’s homes, while there has been general support from the community for this effort, few members of the community have taken any concrete action to help. Working together with a dedicated crew of university students, I have cleaned out three homes as described in Vacant Homes #1, #5 and #7 above. Mr. Arimura was the only member of the community who participated in our work on #1 and a woman from the neighborhood boiled some potatoes and brought them over when we were cleaning #5. It was not until our work on #7 that there was any noteworthy response from the community. In that case a neighbor prepared lunch, another boiled sweet potatoes, two others brought food to snack on and three men showed up to help with the actual physical labor of tearing down two sheds.

I did not solicit help from the community in the hope that people would step forward without having to be asked. Unfortunately, very few did volunteer their time and even the community leaders were generally apathetic as evidenced in their failure to provide information about vacant homes in their respective communities. Only time will tell the degree to which members of the community feel compelled to address this threat to the very existence of their community.

I had initially planned to wait until we had found a potential occupant before making the commitment to renovate Takata’s vacant homes. I had imagined that we could set up a renovation fund and use it to pay for the alterations a new resident required. When the resident paid their rent it would be deposited in the renovation fund until the initial investment had been recuperated. Thereafter, rent money would go directly to the landlord. The landlord, in return for waiting patiently for any income from the home, would enjoy “free” changes to the home that would increase its value. Common renovation work would include, conversion to a flush toilet, conversion from tatami to wood flooring in some of the rooms, replacement of old floor boards, replacement of the kitchen sink and counter, and conversion of the second floor of the adjoining livestock area to a work space or additional bedroom.

While writing this article I received word that the national government will pay for $50,000 of renovation work, enough to prepare two or three homes for occupation by new residents. I will use this money to purchase renovation materials and to pay the wages of a carpenter and a plasterer, two skilled artisans and friends who are familiar with traditional building methods.

Given the large number of homes that are becoming vacant, I can be increasingly selective when determining whether a home should be considered for renovation. A home should be structurally sound and located on a viable plot of land a reasonable distance from neighbors. Ideally the owner should be someone who can be communicated with directly and not through another individual as this is the only means by which to establish rapport.

Finally, I must decide how much time and effort to commit to finding homes and future residents for them. Should I, as an outsider who arrived in this community some six years ago, continue to pursue this work while members of the community who were born and raised here are pursuing their own interests and doing little to help out? Should my efforts be tied to theirs or are these separate matters? I have yet to find the answers to these questions. Time will tell.

Jeffrey S. Irish, a longterm resident of Kagoshima, is a translator and author of books in both English and Japanese ( The Forgotten Japanese: Encounters with Rural Life and Folklore, by Tsuneichi Miyamoto; Doctor Stories from the Island: Journals of the Legendary Dr Koto, by Kenjiro Setoue; My Nuclear Nightmare: Leading Japan through the Fukushima Disaster to a Nuclear-free Future, by Naoto Kan; 幸せに暮らす集落、鹿児島土喰集落の人々と共に;ライフ・トーク、学生たちと歩いて聞いた坂之上の35名), now venturing into TV documentary-making; he’s also an old friend of KJ. He was a major contributor to a special KJ bookzine, Inaka: The Japanese Countryside (KJ 37), which remains available as a back issue.

Photographs by Jeffrey S. Irish