From KJ 37: Inaka

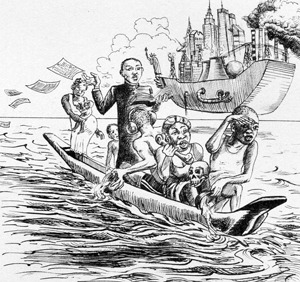

BY PICO IYER, Art by Walderedo de Oliviera

[A]ll the world’s a single unit, the ads and headlines in our newspapers increasingly inform us; I.B.M. promises “Solutions for a small planet” and A.T.&T. boasts of “Bringing the world together.” Bill Gates writes of how the majority of the world’s adults will be wired within ten years, and Nike spots on NHK (not to mention KDD bills) suggest that every part of Planet Reebok is being turned into a One World whole. Even my local (English-language) newspaper here in Nara, where I write this, comes with a small box at the top that says, “Global Magazine for Global Marketing … Reader’s Digest — the Magazine in Globalese.”

[A]ll the world’s a single unit, the ads and headlines in our newspapers increasingly inform us; I.B.M. promises “Solutions for a small planet” and A.T.&T. boasts of “Bringing the world together.” Bill Gates writes of how the majority of the world’s adults will be wired within ten years, and Nike spots on NHK (not to mention KDD bills) suggest that every part of Planet Reebok is being turned into a One World whole. Even my local (English-language) newspaper here in Nara, where I write this, comes with a small box at the top that says, “Global Magazine for Global Marketing … Reader’s Digest — the Magazine in Globalese.”

Globalese, however, was not the tongue that reached me when I set foot in Port-au-Prince not long ago. Women were relieving themselves along the main boulevards, in front of shacks that called themselves the Centre de Formation Intellectuelle and the College Rene Descartes, while buses bumped and lurched over potholes next to the “Sexy Photocopie” shop and the “Wonderful Semi-Lycee.” Along the unpaved main roads there were no signs, no traffic-lights and no central dividers, and next to the national Highway One, the prinicipal roadside attractions on view were tombstones. In the fancy French restaurants in the hills, foreigners (like me) talked about the days when gasoline had been “a hundred U.S. a gallon,” while down near the Presidential Palace, the signs that said, “Tomorrow Belongs to Haiti” were all but obscured by mountains of trash.

Before I had left the airport (where my flight, like all others, was greeted by a four-man troubadour band playing on the tarmac), blood was streaming from my hands, my possessions were (I gathered) in someone else’s hands and the car that was meant to take me into town was getting violently rear-ended (a not inconsiderable feat, given that it could hardly move). It was a salutary, and not unwelcome, reminder of what I call the Haiti Test, the administering of which is the main reason I travel these days: to set topics of the dinner-tables where I and my friends chatter — the rise of Microsoft and the hegemony of America, the “borderless economy” and the growth of multi-culturalism — against the simple, stubborn realities of a world that does not often think of itself as small. And to remind myself (as it is easy to forget, especially in wired Japan) that in most parts of the globe, World Phones, World Planes and the power of the World Wide Web are no more on people’s minds than they were a decade (or a century) ago.

In fact, the world could be said to be growing less and less connected, if only because the gap between the few of us who babble about the wiring of the planet and the billions who do not grows ever more alarming.

In Haiti, where fully 70 percent of the people have no jobs and 60 percent of those over the age of 25 have never had a day of formal schooling, talk of the “home office” and the glories of a virtual workplace seemed to come from another planet. And in the Church of St. Gerard, where girls in fluffy orange dresses were playing voodoo drums (instead of an organ) to parishioners standing amidst pillars that said, simply, “Piety,” “Force,” and “Fear,” “It’s a Small, Small World” did not seem to be on the playlist. Thanks in large part to the progress we celebrate, the gap between the richest 20 percent of the world and the poorest 20 percent has, in fact, doubled over the past 30 years, while an ever greater percentage of our population is represented by those in Sub-Saharan Africa, who are not creating home pages. Even the places that do watch the O. J. Simpson trial or listen to Madonna are no closer to us than they ever were — in India people flock to a McDonald’s outlet where they serve no beef, and in China, 300 million may watch the Super Bowl, but their government remains no less intractable to Western reasoning.

The global village, I mean to suggest, has relatively little application to the real villages of the world (and even to the rural cities), and the amenities of a powerful minority gloss over the realities of a globe that still has all the age-old lusts and worries (even if they can be played out more and more on small screens). And though you sense this when you ride the subway to the end of the line in New York, or step over the border near San Diego, though it’s apparent in the countryside an hour away from Kyoto or walking around the White House late at night, you can feel it most powerfully by visiting a place like Haiti, where phones and computers still seem like props from science fiction. For better or worse (and it’s often worse), much of the world is still caught up in the deathless questions of the Bible and the folktale: how to get food on the table and find shelter for your kids; how to hold onto belief when reality contradicts it at every turn; how to live with neighbors who killed your mother a week ago.

Not all global issues of the moment are beside the point when you walk along the Rue des Miracles, in Port-au-Prince, or past a Haitian hospital nearby (“Arms Prohibited Inside,” it says in two languages). The fate of the United Nations is hardly an idle issue in a country that is tenuously held together, its people told me, by the U.N. Peacekeeping Forces I saw playing volleyball on the beach. And the way new opportunities for communications have helped the drug-trade go global is of keenest interest to a people whose leaders have encouraged the use of their own country as a transshipment point. Yet even those are often lesser concerns in a land where the average man is dead by 44, there is exactly one doctor for every 10,000 bodies and — not coincidentally, no doubt — one child in every ten dies at birth. And our cozy faith in the universality of such local pieties as “one man—one vote” takes on a different meaning in an island where people tell you not to go out at night “because of democracy” and recent elections drew out perhaps five percent of the electorate.

To some extent, we know all of this already, and it has always been thus: the concerns of London and Tokyo have always seemed remote in the provinces, and buzzing cities everywhere occupy a different century from the countryside. But the danger is that these days such truths grow ever easier to ignore, as all the momentum of the age propels us towards a belief in United Colors of Benetton visions. There is jet service to Pyongyang, and Internet access in Cuba, our newspapers inform us (even in Nara); CNN reaches “210 countries and territories around the world,” including even Haiti, it reminds us on the hour. All of which tempts us to ignore the fact that there may be e-mail in Cuba, but there’s little bread, no Tylenol and often no electricity. And Cuba, by the standards of most parts of the world, is well-off. It can be treacherous to submit too readily to the slogans of multi-nationals when, it’s often said, there are more telephones in Tokyo than in the continent of Africa.

The Haiti Test is almost self-administering, and I’ve found it amplified in Bhutan (where there’s no television), and North Korea (where the least of local worries is privacy on the Internet), and Auburn Avenue in Atlanta, where the birthplace of Martin Luther King, Jr. is surrounded by a neighborhood as orphaned or stricken as many in Port-au-Prince. And it has the useful effect of qualifying, when it does not nullify, most of what I might say about the end of history, the world as theme-park or Steven Spielberg’s control upon the global imagination. Insofar as the world is, in some regards, better linked than it used to be, it’s principally useful, perhaps, if it can help us take ourselves back to those places where such developments are hardly known. A holiday in Haiti seemed a slightly perverse idea, I know, and could smack of political voyeurism: yet I rejoice in the souvenirs it left me with every time I read an article (as I did in The New York Times not long ago) about how we’re “Overwhelmed by Good News”—right next to an ad about how we’re living in a world where there are no walls, and only bridges.