On a golden fall day in Darjeeling, hometown of my family on the Tibetan side, I stopped in to see an acquaintance who’d promised to arrange a visit with monks at a local monastery. I was researching a novel and had questions about death rituals and The Tibetan Book of the Dead. “The monks have gone to the cave,” the man informed me with an apologetic smile. I told him I’d come again later in the week, but he shook his head: the cave was in the south of India and the monks would be there till spring.

Although the monks’ departure was a setback for my project, it directed my thoughts onto a path I’d been exploring as I studied The Tibetan Book of the Dead. Composed by Guru Rinpoche, the eighth-century Indian saint who brought Buddhism to Tibet, the book is a guide to navigating the bardo interval between death and rebirth. I’d been ruminating on the metaphorical significance of bardo; that afternoon, as I strolled through the Darjeeling town square past elderly Tibetans counting their prayer beads in the shadow of 28,000-foot Mount Kanchenjunga, I thought about the monks who’d “gone to the cave.” What happened when we left behind our usual way of being and entered an alternate reality?

Now that the COVID-19 pandemic has thrust us into a different kind of existence, I’m wondering the same thing. Not only in relation to bardo and caves but, more than thirty years since moving to Tokyo, in connection with the Japanese concept of ma, a between-space that allows for something new.

My great-grandfather S.W. Laden La, a Darjeeling community leader who worked closely with the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, was devoted to Guru Rinpoche and helped bring The Tibetan Book of the Dead to the West. According to legend, this bardo guide is one of the terma treasure teachings Guru Rinpoche buried in caves in Tibet, and was unearthed in the fourteenth century by a tertön treasure finder. This makes it sound like the tertön dug out the teaching with a shovel but the idea is that he had the correct point of view to locate it in a hidden geography and mindscape.

One of the fundamental lessons of The Tibetan Book of the Dead is that we can only move forward to a new way of being if we accept the truth of our situation. When someone dies, monks sit next to the corpse with the family in the altar room and read aloud from the Book of the Dead, a practice to benefit both the deceased and the surviving relatives as they confront their new realities. The dead person may hover around, refusing to acknowledge she has died and wondering why her loved ones are weeping. Unwilling to let go, the family may beg her to return. As the monks read, Guru Rinpoche’s wisdom is revealed to all who are open to hearing it: O nobly-born, that which is called death hath now come… Do not cling, in fondness and weakness, to this life… Thou hast not the power to remain here.

The cave with the hidden Book of the Dead is a powerful metaphor for the pandemic interval we’re experiencing, a between-space whose teachings are accessible if we have the right perspective. While seeking enlightenment in a cave, monks contend with hunger, cold, wild animals. Our challenges during COVID-19 may include isolation and illness, fear and grief, a profound longing to return to the way things were. But if we keep our minds calm and focused, we might unearth wisdom: consciousness of impermanence, appreciation of our interconnectedness, acceptance of what comes in life. With our thoughts, we have the power to create our experience of the bardo we’re traveling through.

Since early times, people have meditated in caves and brought home relics to help maintain the awareness gained: a stone, a leaf, a bit of soil. I like to think that during this pandemic, we’re developing a deeper understanding of ourselves and the world; whether or not we bring back relics when the crisis is over, I hope we’ll keep a new consciousness with us. On days when I feel pessimistic, when it doesn’t seem like I’ll attain any enlightenment in this cave, I take heart from what a Rinpoche in Darjeeling once told me: However benighted we are, we can benefit from the Buddhist teachings “like an ant circling a stupa on a piece of dung in a flood.”

As for ma, over my years in Tokyo I’ve encountered it as silence during conversation, as negative space in rooms and gardens. It first felt empty like loneliness, rather than empty like solitude. But I’ve come to see it as an opening for creative contemplation, for exploration and insight. The epidemic interval we’re experiencing is an in-between like ma, like bardo, like the cave where The Tibetan Book of the Dead was found: space charged with possibility.

Featured in digital issue KJ98: ma, a measure of infinity

Ann Tashi Slater is working on both a memoir and a novel based on the family story in “Tibetan Butter Tea and Pink Gin.” She’s been published by The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and The Huffington Post, as well as Shenandoah, New World Writing, and Asia Literary Review, among others. Her work appears in Women in Clothes (Penguin) and the YA anthologies American Dragons (HarperCollins) and Tomo (Stone Bridge). Her translation of a novella by Reinaldo Arenas was published in Old Rosa (Grove). A longtime resident of Tokyo, she teaches at a Japanese university. Visit her at www.anntashislater.com and her HuffPost blog: www.huffingtonpost.com/ann-tashi-slater/

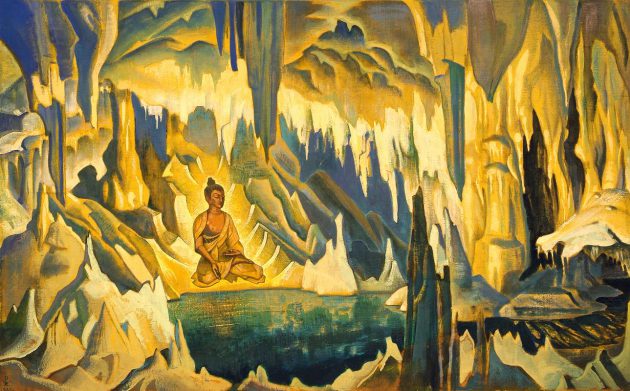

Header image: “Buddha the Winner” by Nicholas Roerich 1925,

Roerich Museum, Moscow, Russia