Joshua Shapiro

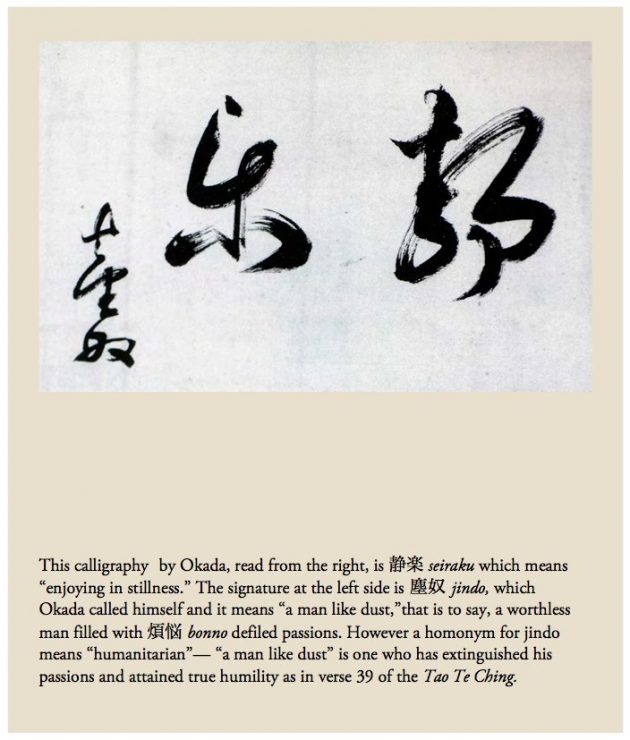

The way that can be told, is not the true way…

He who knows, doesn’t talk; he who talks, does not know.

—Lao-Tzu

Much like the Tao, the work of Okada Torajiro (1872-1920) is perhaps more easily defined in terms of what it isn’t. He offered to the world Seiza, a simple means of self-development, founded on a proper sitting posture and a correct breathing method. Seiza is totally experiential. Okada didn’t boast or make promises. Long before Nike existed, he told people, “Just do it.”

If religion is really all about salvation, then Seiza (literally “quiet sitting”) is religion devoid of trappings. Hyper-minimalistic, it eschews external organization, temples, tithing, dogma, theory, canon, worship, beliefs, literature, scriptures, calendar, prayers, hymns, priesthood, hierarchy, relics, icons, saints, homage, cults of personality, holidays, myths, cosmology, symbols, architecture, laws, commandments, uniforms, or costumes.

Seiza is not tied to the intellectual, rational, or medical. It does not depend on emotion, bhakti (piety), or devotionalism. Neither is it otherworldly, mystical, or renunciatory. It is not tied to a particular race, ethnicity, or culture. It is not congressional and needs no pilgrimage. It does not proselytize or support military aggression. To actually practice Seiza, one needs no group or leader, no visualization, vocalization, counting, or mantra repetition, and no special symbolic objects, apparatus, or vestments. Seiza is truly more zen than Zen.

For someone who was in the public eye, eighteen hours a day, seven days a week for over a decade, Okada remains an enigma—a public figure with virtually no well-documented backstory or salient personality. Much has been inferred, and some surmised about his life and past, but facts are few and grasping his particulars is like bottling smoke(1).

At the end of March, 1906, Okada literally just appeared in Tokyo, having walked the entire way from his home in Toyohashi, one hundred seventy-seven miles away. For 10 days he had slept out in the open and fasted. He was near starving and had lost significant weight. He made his way to the home of his elder brother, Okada Tōjuro, visited a short while, and then went on to stay at the residence of Matsui Yuzuru, the former county executive of Atsumi-gun. He lived in a room there for the next two years, eschewing most outside contact.

It is thought (2) that Okada was born in 1872, the fifth year of the Meiji era, and grew up in Tahara-machi in Aichi-ken. The second son of Okada Nobukata, of a minor samurai family, as a youth, he attended school and labored in the family rice fields. Prematurely born, he was a delicate child subject to childhood disease and interested in physical culture. From his teens, he was a seeker on the path, interested in both agricultural innovation and human development of mind and body. He studied the educational ideas in Japanese translations of Rousseau’s Emile or On Education and Plato’s Republic. He also read the teachings of Confucius, Jesus, Lao-Tzu, Buddha, Mencius, Shinran, and Hakuin.

At fourteen, while sitting by a rice field, watching the sun set, he experienced a self-awakening (3). He sought out renowned priests and received spiritual training in zazen meditation. He made pilgrimages to meet notable Edo-era thinkers, philosophers, and statesmen, searching for answers. He visited Buddhist temples, observing the Buddha’s posture in statues. He took daily cold water baths in the early morning.

Ninomiya Sontoku (1787-1856), a practical agronomist, clear-eyed regional administrator, economist, philosopher, and moralist, was a particularly strong influence on Okada and a great teacher by example. Ninomiya, who grew up orphaned and destitute, sustained severe hardships as a youth, but by intelligent hard work, and sound judgement, was able to restore his fortunes.

Seeing his example, local lords assigned Ninomiya the mission to rescue regions in their dominion that had fallen into moral decline and agricultural neglect. Ninomiya practiced frugality and benevolence, sacrificing himself to save others. He lived on a diet of rice and vegetable soup, sleeping only four hours a night.

Once, Ninomiya sequestered himself at a temple to pray for guidance, fasted twenty-one days, then, with seemingly superhuman endurance, returned on foot the fifty miles to his village in a single day. Okada sought out his followers to gain guidance. Much of Okada’s later life was foreshadowed by this powerful role model of selflessness, duty, and rigorous self-discipline.

Like Ninomiya, Okada believed that agriculture was the foundation of Japan. Okada became an agricultural researcher seeking to improve rice yields. He graduated first in his class from agricultural college. Studying rice, he came to better understand its nutritive requirements. He also found natural ways to exterminate insect pests that attacked rice crops. His results were published in national agricultural journals. At twenty-six, he was appointed as head of the agricultural extension service of Atsumi-gun county in Toyohashi, where he worked for three years.

Okada took his work seriously. He made friends and he made enemies. He was brash, outspoken, and didn’t suffer fools lightly. In a conformist society, where a decisive principle was deru kugi wa utareru (“the peg that sticks up will be pounded down”), his evident traits did not sit well with the mayor—who fired him.

Finding Japan too narrow and confining, Okada set sail for the U.S., a more open society, to find answers to his questions in entomology, eugenics, literature, and philosophy (4). Kanahara Akiyoshi, a very wealthy businessman and founder of Kanahara Bank, gave Okada 3000 yen to fund his travel and living expenses (5).

His three-and-a-half year stay in America is similarly opaque, but through sometimes conflicting accounts, pieces can be patched together, while still leaving giant gaps and uncertainties. He arrived in San Francisco on July 9th 1901, where he took lodging at 935 Sacramento Street. He was diligent, driven, and widely read, studying from dawn to midnight. He acquired a reading knowledge of English, German, and French. He seriously investigated the thought of Plato, Homer, Jesus, Luther, Shakespeare, Rousseau, Goethe, Beethoven, Swedenborg, Longfellow, Irving, and Emerson (6).

He met Eugen Sandow, the father of modern body-building. He attended Quaker “waiting worship” meetings. He visited Luther Burbank, the pioneering botanist, at his experimental station in Sonoma County, California. He traveled to Palo Alto to meet Vernon Lyman Kellogg, the entomologist and expert on silkworms, and perhaps also David Starr Jordan, the Stanford University president, eugenicist, and peace activist. He might have visited Salt Lake City where the grand temple of the Latter Day Saints had recently been completed.

America appeared to agree with him and he expected to continuing studying there. However, an arranged marriage thoroughly disrupted his plans. In 1904, he was engaged to Yamamoto Kiga, the 23-year-old daughter of a Toyohashi banker. Okada returned to Japan via Europe at the beginning of 1905 and married her at the end of March. In March the following year, Michiko, their first child, was born. At that point, instead of joy, an unbridgeable gap arose.

Okada had a utopian streak and envisioned creating an ideal, self-governing village. His ambition was to start a school and devote himself to spiritual education for human development. This clashed with the intent of the wealthy Giichiro, his practical father-in-law, who expected him to take over and grow the family businesses. When their differences could not be reconciled, Okada was ordered to divorce Kiga, give up the Yamamoto name, and exit the Yamamoto house immediately. As he embarked at midnight, Okada insisted that Kiga stay with her family, to take care of her newborn daughter. He then set off into the night, bereft of food or money.

***

Careening from the Tokugawa period into the Meiji, Japan entered an extended identity crisis. The Tokugawa Shogunate had blessed Japan with over two hundred years of sustained peace. The Meiji era was not as benign. A national conscript army, established in 1873, fought recalcitrant samurai for several years and was then sent into battle overseas in Taiwan, Korea, China, and Manchuria.

The Russo-Japanese war of 1904-05 was particularly significant as it established Japan as a Great Power. Sometimes considered World War 0, it was noteworthy for its horrific precedents of sustained trench warfare and deadly naval battles, augmented by technological advances in killing, that would reappear in Europe a decade later. The first time that an Asian nation had defeated a Western country, it highlighted Russian incompetence—resulting in the subsequent decline and overthrow of the Romanov dynasty—challenged the notion of white supremacy, and stimulated anti-colonial feeling throughout Asia.

Japan basked in its newly-won prestige, albeit at significant cost. Japan lost nearly 100,000 lives, gained little territory, and did not receive financial reparations for the substantially borrowed ¥2.15 billion (7) it expended, leaving the Japanese public feeling ill-treated by the peace process. Riots in Tokyo alone, immediately following the Portsmouth treaty, left over 1,000 casualties and substantial animosity towards America.

In the Meiji, everything was in play. The abolition of feudalism made possible enormous social and political changes. Social relationships shifted. The nameless could take surnames. Caste-based occupational and marriage limitations were abolished. Millions of people were suddenly free to choose their occupation and move about the country without restriction. By providing a new environment of political and financial security, the government encouraged investment in new industries and technologies.

With new opportunity came new insecurity. Edo-era traditional relationships, reciprocal obligations, and social support structures crumbled. Physical and psychological dislocation followed. Millions left close-knit rural communities for urban crowding, anonymity, and isolation. Fealty and duty to feudal lords were replaced by commitments to factory owners. Industrial progress and military prowess gained preeminence over agricultural productivity. Alien culture, religion, science, literature, and politics became forces to be reconciled, as Japan traded more with Europe and America.

Serious questions of identity loomed large. National identity—what was Japan’s true national essence (kokutai)? A relevant slogan of the times was wakon yōsai (Japanese spirit, Western intellect). Could Japan maintain its culture under the onslaught of Westernization? Individual identity—how could one shape a personal identity without reference to the state? What were the legitimate rights of an individual and how might they supersede an individual’s debt to society? Should one be patriotic or pacifistic? Asian identity—how could Japan justify and sustain wars and colonies with its Asian neighbors? Was Japan culturally superior to other Asian countries? World identity—in what manner was Japan to be a Western power? How much interdependence via alliances and trade could it accept? Could it be both politically bold and culturally derivative? Social identity—how could the educated classes deal with the rapidly rising working class, freed from feudal bounds? How could the nation maintain any cohesion between the stable countryside and the rapidly growing cities? Family identity—could youth respect and benefit from their elders’ hard-wrought experience during a time of radical transition? Could multi-generation rural living arrangements survive divisive urbanization and industrialization? Should women have the same rights and opportunities available to men?

Nowhere did these issues become more apparent than with students who while growing up needed to define themselves as autonomous individuals and navigate the shoals of competing ideas, movements, and dogma. They were the ones called to fight and die. Anguished youth suffered from isolation and loneliness, having broken ties with traditional values, their families, and society. Conflicting stresses on their identity manifested in multiple youth cults of hedonism, existentialism, patriotism, socialism, anarchism, spiritualism, and angst. In these matters of self, youth were called to choose a polarity or resolve the duality.

Staying physically healthy was also a widespread social concern. Annually, 100,000 Japanese died of tuberculosis. Every decade or so, Japan experienced a massive cholera epidemic decimating tens of thousands. Famines were not a distant memory. On a less lethal level, but still very debilitating, a new disease appeared, a critical loss of vitality—neurasthenia, a condition characterized by physical and mental exhaustion, accompanied by headaches, insomnia, and irritability. Attributed to psychological issues like weakness of spirit, depression, emotional stress, or conflict, it was considered a root cause of personal failure.

It was into this tumultuous flux that Okada walked.

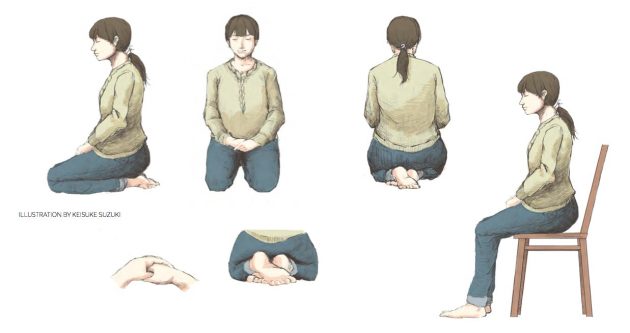

When Okada first formulated Seiza is unknown, but he researched and practiced breathing and posture over the two years he was sequestered at the Matsui (8) residence, refining what was to appear as his Seiza methodology. The traditional Japanese posture used in the tea ceremony or martial arts, also called seiza “right sitting,” morphed into Seiza (“quiet sitting”) (9) Okada’s approach to self-awakening.

Okada preferred this archetypal, informed form to harmonize body, mind, & breath. The body assumes a stable pyramid, plumb and erect, with the xiphoid (10) pointing down into the center of the triangle formed by the two knees and the perineum, opening the door to the mind and centering the sitter within a radiant sphere. Seiza posture promotes the efferent parasympathetic nervous system, which governs the “rest & digest” response, by aligning the skeleton to ease passages of the cranial and sacral parasympathetic nerves. Activating the parasympathetic aspect of the autonomic nervous system, deactivates the sympathetic nervous system governing “fight or flight,” and so facilitates the body achieving a deeply relaxed, rested, and rejuvenated state.

When Okada emerged from his self-imposed chrysalis, his caterpillar had lost its brashness and restlessness. In its place was a butterfly radiating healthy vitality, peaceful tranquility, and gentle love for all. Having transformed himself, he was ready to share with others of the same mind. He taught things that were so easy, they were hard to accept. His point was if you do the practice, you get the results. Books are easily misunderstood. The universe offers direct revelation; one doesn’t need books have an epiphany. You can’t ask someone else how things taste; you must taste them yourself. It’s not about discussion, reading, studying, or praying; just practicing the practice.

He did not pose as a teacher, nor did he preach. He was simply the exemplar for his method, just a co-learner (11). People saw someone who was solid, rooted, centered, balanced, and grounded, but still flexible, resilient, supple, and elastic. Someone agile, nimble, and alert. Someone clear of eye and clear of voice. Someone with a shining countenance, like Prince Genji, engorged with life force, so filled with energy, his vigor altered people’s perception. People who sat Seiza with him felt better. They healed themselves (12). Japanese doctors even adopted Seiza as part of their regimens.

His Seiza practitioners witnessed a indefatigable man, like Ninomiya Sontoku, devoid of leisure, devoted to his mission, working dawn to midnight (13), seven days a week, without interruption or vacation, yet without haste, fatigue, or irritability. Each day, he would rise before dawn, take a cold bath, eat a breakfast of rice with pickles, and set out to visit a dozen Seiza meetings held all over Tokyo in different private homes, halls, and temples. In each session, he would guide from a few people to a few hundred, from forty minutes to an hour, at each successive venue. Most of each sitting was in total silence. Okada might gently touch someone to adjust their posture. Afterwards, he would stay to quietly answer a few questions. From this interaction, collections of sayings were compiled and some anecdotal personal history was collected.

Diverse notables and commoners within urban Japanese society—the Imperial family, former daimyo, military officers, bankers, businessmen, diplomats, politicians, professors, physicians, scientists, artists, university students, but also housewives, and farmers in the countryside—came to sit with him. He appealed to such a varied mix by providing a uniquely individual path that was outside and above the polarities of the economic, political, and social pressures they confronted. He also attracted those troubled by illness or infirmity, for whom neither Western medical science or traditional Asian cures yielded results. By 1918, without social media, over 20,000 Japanese were practicing Seiza.

Okada taught silently by example. He walked the walk, content without fancy food, stylish clothes, or comfortable lodging. Back in his simple room at Matsui’s home, he would record his day, take another cold bath, and be asleep after midnight. He achieved this routine, not though austerity, but by impartiality (14). He didn’t counter nature with penance, as much as blend his actions with nature in a relaxed, pleasant, and easy manner. Likewise, he sought to steer people away from the competitive industrial environment and nationalist military path that Meiji rules promoted, typified by the popular slogan fukoku kyōhei (rich country, strong army). He understood that so-called heroism was false courage and unsupported bluster.

Okada had exemplary health. However, in 1920, when he moved in with his wife and daughter, his health declined precipitously. His close followers attributed his illness to overwork. He burned all his diaries, his small self (小我shoga), that he had meticulously kept for over a decade, preventing access to them while he was out of the house, traveling, or after his demise.

Many expected that Okada would live forever and were dismayed and disillusioned by his death (diagnosed as acute renal failure) at 49. All he left in writing from his life’s work was a scrap of paper found in his pocket that hinted at his final act of impartiality and self-sacrifice:

Man has a more important job (shokubun) than supporting a wife & children. What is this occupation? To sacrifice oneself for the liberation of the Japanese race (yamato minzoku) from the restraint (sokubaku) of conscience (ryōshin-teki) and to lead it to the freedom of heaven and earth (jiyu no tenchi).

A cadre of his most devoted students maintained his teachings and issued books of his sayings that they had collected. Okada himself never published his teachings, started a school, sought fame or fortune, or was at all self-aggrandizing. He was never recognized as the great Taoist master that he was, a simple man who sought, found, and shared the Way. He did his thing and left the scene. His achievement was in the simple but effective method he developed. He pointed to the door and beckoned people to enter. While few now know of Seiza or practice it (15), its value is undiminished. A diamond found in the muck remains as durable and valuable today, as when it first appeared.(16)

Footnotes

1. Much as with the eighteen (between 12-30) “unknown years of Jesus”.

2. The following narrative and dates regarding Okada are drawn primarily from:

岡田虎二郎 その思想と時代 Okada Torajiro sono shiso to jidai (Okada Torajiro, his thought and time) written by 小松幸蔵 Komatsu Kozo, 10/10/2000, 創元社 Sogensha and 岡田虎二郎先生 生誕百四十年記念 静坐創始者 岡田虎二郎 Okada Torajiro sensei seitan hyakushijunen-kinen, Seiza soshisha Okada Torajiro

(Commemoration of the 140th of his birth; Okada Torajiro, the Founder of Seiza) edited by 田原静坐会Tahara Seiza-kai, 6/17/2012, 田原静坐会 Tahara Seiza-kai)

3. It is interesting to note that the spiritual awakening experiences of his contemporaries, Swami Vivekananda and DT Suzuki, first took place in their mid-twenties.

4. One of the core mandates of the Meiji Charter Oath of 1868 was to seek knowledge outside of Japan. But no one knows how Okada decided to leave Japan or prepared for his journey.

5. While hard to quantify, this was an enormous sum, more than $60,000 in today’s currency. One yen could purchase 42 pounds of rice.

6. Okada ultimately formed a personal library of 247 books in Western languages, that still survives.

7. In current (nominal) Yen.

8. As the go-between between the Okada and Yamamoto families, Matsui Yuzuru bore some responsibility for the lack of clear communication of their intentions, and therefore the ultimate failure of the marriage.

9. While pronounced the same, the kanji are different: 正座 “proper sitting” as found in the tea ceremony or martial arts versus 静坐 “quiet sitting” as taught by Okada.

10. xiphoid process—the little “arrow” of cartilage extending below the sternum.

11. This section draws on The Okada Method of Seiza Culture for Mind and Body, The Okada Science Society, 1918.

12. Okada healed by teaching the patient seiza and sitting with them. He reportedly completed cured one of Matsui’s sons who was considered ‘insane’ by sitting with him for a week. Koeda Heijiro, a Japanese diplomat serving in Vienna, Austria, was recalled to Japan when he contracted serious pulmonary apicitis, an extreme form of bronchitis. He recovered by doing Seiza with Okada.

13. His Wednesday schedule, for example, started at 6AM with sitting at Nippori Hongyo-ji temple, then holding successive meditation sessions at the residences of Itsume, Kuga, Fukahara, Okuma, the sculptor, Kawada, the Hosokawa (former daimyo family) palace, the Kyozen-ji temple, and finally the residences of Kyogoku, Iwaki, Minegishi, Eguchi, and Suzuki.

14. By not holding to an idea that one thing, situation, or person is should be preferred over another. Relinquishing duality is attaining impartiality (平等心 byodoshin, equal heartedness).

15. Perhaps fewer than one thousand people regularly practice Seiza today.

16. Acknowledgements: Producing this article would have been impossible without the sustained, generous, and patient help afforded me by Rev. Miki Nakura, Buddhist Priest of the Higashi Honganji Temple, and Seiza teacher, who worked with me to access and translate most of the primary source material on Okada Torajiro. He also rigorously checked my manuscript for accuracy. Any textual errors or opinions are mine alone.

I am also grateful to Kurita Hidehiko, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), for his introduction to Nakura-sensei and his provocative theories about Okada. Cindy Slater, of the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports at the University of Texas at Austin, tirelessly provided key documents and was a wonderful resource about global physical culture at the cusp of the 20th century.

A simple sitting and breathing method established by Okada Torajiro

Sometimes the mind will drift back up to the head. Gently return the mind back to the tanden, the lower abdomen. Eventually, it will sit there, the mind and body as one. Sitting happens; effort is not necessary.

Should the feet go numb, lift the buttocks off the ankles and stand on the knees for a few minutes to regain circulation. If one can’t comfortably assume a kneeling position, sit on the front third of a chair, maintaining the rest of the posture.

Start practicing this breathing method for 10 minutes, twice a day. Work up to 30 minutes on arising and 30 minutes before retiring to bed.

Once entering a state of calmness, maintain this state during the daily routine. Live a quiet but active life in this peaceful state to be truly happy. Practice. Seiza is the fundamental work of a lifetime.

Our human vices, the sorrows of humanity, are caused by external matters that undermine emotional balance. To be saved from these vices, one must have a healthy body and upright heart. These can be achieved only ‘on the way’ 道 (michi ≈ tao). To reach the way means seiza ‘sitting.’ If you sit for two or three years, you will understand naturally.

Just sitting seiza alone is not sufficient; all our behavior—walking, standing, sitting, reading, writing, working, even cutting tofu must come from hara 腹. Our entire daily lives must reside in tanden.

Do not dare to strive. Sit down quietly in the country of no seeking. If there is but a space three feet square to sit, the spring (season) of heaven and earth will fill this space and the vital life power (人生の力 jinsei no chikara) and joy (悦楽etsuraku) of our lifetime arise within it. Seiza is truly a gate (mon) into great rest and happiness.

Like a five-story pagoda (gojū-no-tō ) supported by a massive center column (shin-bashira), so faultless should your posture be. Seiza posture parallels nature. Why does a five-story pagoda not collapse? Because it maintains physical balance. If one sits in the seiza posture one does not topple over no matter from which side one may be pushed.

The essence of seiza is not limited to the sitting form. I introduced this kneeling style because it’s well suited to the Japanese sitting custom. Were I European, I would teach with dance. We cannot dance if our center is not stable, firm, and balanced.

Seiza seeks the perfection of the human being. The achievement of health and the acquisition of healing powers are secondary factors. Even if the body is changed in seiza, the deepest inner state does not change so quickly. You sit for one year, two years, three years, and you think that you are like one born anew. In truth, however, you are just a little shoot on the way to the development of your being. It takes ten to twenty years to become like the cedars and cypresses rising to heaven. A cypress increases its rings even as a very old tree. One should continue to grow up until the very moment of death.

The aim of seiza is to do seiza. Don’t think of results.

Ordinary people breathe eighteen times a minute. Less than ten breaths are enough for those who practice seiza. But it is excellent if one can manage with three a minute. (An exhalation should be at least four times as long as the inhalation.)

If one separates people into ranks(高下 kouge) , the lowest class trusts their heads. They endeavor only to gather information and amass as much knowledge as possible. Their heads grow larger and are easily toppled, like a pyramid standing upside down. They can imitate other people, but they never do original, creative, or inventive work or become a great entrepreneurs.

For the middle rank, the chest (胸 mune) is most important. People with discipline, endurance, and abstinence are of this type. They display outward courage but lack real strength. Many of the well-known, great men are of this type. Yet, they are not so great.

But those who regard the lower belly (下腹 kahuku) as the most important part, and so have built the palace where the Divine nature thrives—these are the people of the highest rank. They have developed their minds, as well as their bodies correctly. They emanate strength and reside in ease and equanimity. They act in good faith without violating any law.

The true meaning of education is to draw out the original nature of the individual. This leads also to the perfecting of the personality and the awakening of the soul. Knowledge of the ways of the world cannot be attained by ordered, logical thinking. If one can ‘look’ into that true knowledge that arises from the body’s center, one will understand the ultimate meaning of all the world’s appearances.

Insisting on loyalty and patriotism will destroy the country. Respect for the emperor, love for the country, reverence for a religious founder are not true love only relative. Forcing these thoughts on others is dangerous. Big pure true love equally covers all heaven and earth, class, rich or poor, high or low, citizen or foreign, human or animal.

You have compassion for the poor and laborers but no sympathy for the wealthy. This is not true love. I feel pity for those with fame and fortune. From the viewpoint of self-cultivation, they are inferior to poor people. Many feel pity for the poor, few feel sorry for the wealthy. This thinking is not true love.

If you come and practice with me, it is true, you will not accumulate knowledge, but you will learn to understand the speech of birds.

Seiza Groups in Japan and the USA:

京都静坐会 Kyoto Seiza-kai

contact: Mr. Matsushita, Email: matufumi1220@gmail.com, phone: 090-3625-4071

website: http://www.seizanotomo.jp

大阪静坐会 Osaka Seiza-kai

address: Joko-ji temple, 1-32-4, Higashi-mikuni, Yodogawa-ku, Osaka

phone: 06-6391-5319, website: http://www.seizanotomo.jp/

東京静坐会 Tokyo Seiza-kai

address: Kyobashi Kuminkan, 2-6-7 Kyobashi Chuo-ku, Tokyo

phone: 03-3561-6340

New York Zendo, 223 East 67th Street, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10065

phone: (212) 861-3333, website: http://www.daibosatsu.org/nyz-calendar.html

contact: Miki Nakura Email: mikinakura87@gmail.com, phone: 1-917-769-8253

PO Box 103, New York, NY 10113, USA

Joshua Shapiro lives in New York.

Illustration by Keisuke Suzuki.

Fundamentals of Seizo section by Joshua Shapiro and Miki Nakura.