As deftly as any yojijukugo (Japanese four-character idiom), the anthropologist Mary Douglas here captures the essence of food in just four words—‘Food is not feed’.

Without food we would die, but the true significance of food emerges only after the basic level of subsistence has been reached. Food is both symbol and sustenance, linking body and spirit, self and society, past and present, myth and magic. Cuisines are not just cookery techniques, menus, recipes and ingredients—they are culture, history and memory in edible form. All societies make different choices about food—how it is cooked, eaten and served; which foods are appropriate for which meals, which foods are ‘good’ and ‘bad,’ and much more.

Different foods and ways of eating mark the boundaries between social classes, genders, ethnicities, religions, regions and nations. National cuisines and dishes inspire strong passions, embody national values and identity and are believed to be linked to the nation’s character, health and fortunes. To consume national dishes is not just an act of eating—it is the creation of the nation within the self. The same is true of cuisines dictated by religion, in which eating becomes a spiritual practice, and each meal a kind of sacrament. This is why different societies—or the same society in different periods of history— can begin with similar ingredients and end up with entirely dissimilar cuisines. And of all the world’s cuisines, none is more distinctive than that of Japan.

‘A feast for the eyes’… ‘too beautiful to eat’ are the descriptions Westerners habitually apply to Japanese cuisine, specifically to kaiseki. This is the formalised system in which fresh, seasonal foods are prepared in particular ways and presented with great elaboration, following a formula of courses and dishes that leaves room for the ingenuity and refinement of individual chefs. There are several sorts of kaiseki. First, the very elaborate, luxurious ones served at specialist restaurants which imitate the grand banquets of the nobility in the militaristic late Muromachi period (1337- 1573CE) that saw the emergence of the samurai, and which emphasised luxury, display and differences in status, for those of different ranks were served different foods at the same banquet. Second, the simpler—even austere—kaiseki associated with the rise of the tea ceremony (wabi- cha) under Rikyu (1522-1591) and other tea masters, which emphasised restraint, spirituality and community, for at these meals everyone ate the same food, regardless of status. Finally, there are private and domestic versions of kaiseki meals—these days usually only seen at New Year, and key family events. All three follow the same general principles.

The colours of and patterns on the serving vessels change to harmonise with the season and occasion— brown, red and gold for autumn, pale blues and greens for spring and so on. Shape and form are crucial—round pieces of food should be placed on square dishes and square pieces of food on round dishes and in particular locations on the plates. There is a special word— moritsuke—for the different ways food should be arranged for serving, including sugimori— strips and slices of food in a slanting pile, and yosemori—two or three contrasting ingredients arranged next to each other. Each arrangement incorporates contrasts of texture and hue and there are also seasonal garnishes—fresh green leaves for summer, pine and bamboo for winter. Although they were expanded in the modern period, the original cooking techniques were limited to boiling, simmering and grilling, using only fire and water—there was no frying or cooking with oil. Elaborate rules govern every stage of preparation—the way the knives should be held, different cutting movements in which knives are wielded like swords, specific areas on the cutting boards where the foods should be placed before and after slicing. Similarly, a complex etiquette dictates the sequence in which dishes should be consumed, and the manner of eating them, in which any noises associated with eating or digestion are subject to extreme disapproval. Both intensified and disguised, the food becomes supernatural. So dazzling is the artistry of kaiseki, that no one stops to ask—why?

In food studies and gastronomy, there has been too much of a tendency to simply accept the ‘aesthetics’ of Japanese cuisine as a given, without asking how and why this singular approach to food came about. Although most people think of the ‘traditional’ Japanese cuisine as having its roots in the kaiseki of the late Muromachi and early Edo (1603-1868) periods, Japan and its way of eating are far older. To find out how and why the Japanese came to ‘eat with their eyes,’ it is necessary to cross a bridge of dreams.

‘As I Crossed A Bridge of Dreams’ is the title of a work, also known as the Sarashina Diary, written by a lady of the royal court in the Heian Period (794-1185) when many distinctive features of Japanese culture emerged. It is part of a remarkable body of narrative literature called monogatari, written by court ladies, the best known of which is The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu. These, along with the diaries of leading male courtiers, give insight into aristocratic life in Japan in the ninth century AD, when the imperial court was still the centre of power in the country, before the rise of the shoguns. Set in a place known as the City of Crystal Springs and Purple Hills, now Kyoto, to which the capital had moved in 794, the monogatari and diaries depict an enclosed imperial world very different to the militaristic Muromachi era and the showy society of the Edo period in which the luxurious style of kaiseki would later flourish.

The capital was the symbolic centre of the nation, the palace complex was the symbolic centre of the city, within the palace complex were the country’s administrative and ceremonial offices, and at the heart of it all dwelt the Emperor. There were not yet any samurai and, as this was a time of peace, culture rather than military prowess became the arena in which courtiers sought to distinguish themselves. Poetry, the arts, specialised knowledge, sartorial style and material display flourished at court, turning the period into a golden age of taste and refinement.

In the monogatari, almost every sense is appealed to. The seductive perfume of incense, the sheen on lacquer work, the silken robes worn by men and women, the elegance of the motifs on hand-painted fans are all described in loving detail. The beauty of tableware—already highly sophisticated—met with lavish praise, yet the foods they contained are strangely absent from the scene. In The Tale of Genji, Murasaki Shikibu writes of a banquet held by the Emperor under a cherry tree in the southern court of the palace. There was a poetry competition, followed by music and dance performances, the beauty of which brought tears of admiration to the eyes of the guests. Prizes were awarded—and then the banquet was over, without food being mentioned. There is no Heian poetry that celebrates the delights of food, such as was being written in contemporary Song-Dynasty China. Generally the attitude to eating was negative. Food was thought ‘vulgar,’ and for both men and women, if one had to eat in public, the thing to do was to pick daintily, not consume heartily. One diarist, Sei Shonagaon, author of The Pillow Book, went so far as to write— ‘I cannot bear men to eat when they come to visit ladies-in-waiting at the palace.’

Religious belief in Japan during the Heian period was complex and contested. The indigenous religion of Japan was the animistic worship of kami—numerous nature spirits, elemental forces, local deities and the gods and goddesses of sun, moon and storm. A figure of some 3,000 kami has been given, but they were countless. Out of this grew what became the state cult, called Shinto today, the veneration of a particular set of indigenous deities connected to the imperial family, who claimed divine descent. Interwoven with these were imported beliefs including a version of the two-principle (yin yang) and five-element system brought from China—the dynamic interplay of cosmic forces that had to be kept in constant harmony and balance, known as ommyodo in Japan. To these were added Buddhist elements from the mystic Tendai and Shingon sects then in fashion among the aristocracy, which posed a religious threat to the authority of the kami and the state cult. The importance of ritual generally was intensified by Confucianism which, while not a religion itself, held that ritual and its proper observation was a moral duty and cardinal virtue. These elements came together in a convoluted web of beliefs and practices that included geomancy, astrology, divination, prediction, malevolent spirits and hauntings, the belief in unlucky directions and unlucky days, and the interpretation of dreams and omens. The annual ritual calendar—an endless procession of festivals, offerings and ceremonies meant to ensure the well-being of the nation and the fertility of the land—was followed scrupulously by the court, led by the emperor—according to detailed manuals of procedure which set out exactly how ceremonies were to be conducted, including where to stand at different stages of the rite, what to wear and when to perform ritual claps. The meticulous performance of ceremonies and rites great and small was believed essential to keeping chaos and misfortune at bay.

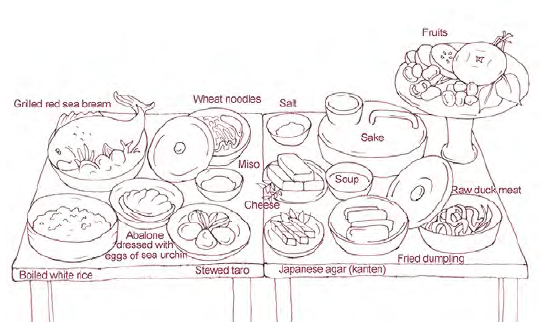

Every ceremony was accompanied by food offerings using pure water and fire, made in the royal kitchens, which were culinary temples in their own right presided over by their own kami. The manner of preparation was specified in the manuals, and laid upon the altars in particular ways, with the emphasis on purity. These were the first fruits, the choicest produce of land and seas depending on season, arranged in various ways in special vessels, during ceremonies involving elaborate ritual movements. Here can be seen the real origins of Japan’s distinctive cuisine. Often described as ‘ritualized,’ it is ritual itself—the rites that embody ancient beliefs whose meanings have been largely forgotten, originally performed to mark the seasonal cycle and keep the cosmos in order and harmony. By eating food prepared and presented in the same way as the offerings, daily meals became a sacrament and a part of Japanese identity. But what accounts for the ambivalence about eating and the invisibility of food in Heian monogatari?

The answer lies in myth. According to the ancient chronicles the Kojiki, the Nihonshoki and other sources, the brother of the Sun Goddess went to visit the deity of food, variously named as Ogetsuhime, or Ukemochi, sometimes described as male and sometimes as female. Wishing to honour the guest with a banquet, Ukemochi/ Ogetsuhime expelled rice, fish and ‘smoothhaired and game from her nose, mouth and rectum, spreading the food upon a hundred tables. The divine guest was so disgusted—‘How filthy! How vile!’—that he drew his sword and killed Ukemochi/Ogetsuhime. Hearing of the outrage, the Sun Goddess sent a messenger to the scene, who according to the Kojiki, found that the body of the dead kami was continuing to produce food and useful things—horses and oxen, millet, silkworms, rice, wheat and beans continued to pour from different orifices of her body.

These mythic origins help to explain the deep ambivalence about food and eating that pervades Japanese culture even today, and explain the displacement into aestheticism. To remove food from its impure origins, everything had to be done to make it look beautiful, to raise it to a higher plane where it could be consumed with the eyes, as well as in the ordinary way. And the old limited cookery techniques of fire and water can be seen for what they are—purifying and cleansing procedures originally used in the worship of the kami, avoiding oil, which was seen as impure. Truly, in Japan food is not feed, and its traditional cuisine links symbol and sustenance, body and spirit, self and society, past and present, albeit with one difference. In Heian times, the emphasis was not on the flavor of things, but on their appearance and purity. With the addition of frying and more meat in the diet, contemporary kaiseki food is tastier than it was when the Japanese first began to eat with their eyes, but plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose—the more it changes, the more it remains the same. When you next eat one of these meals, remember that you are not eating ‘art’, but feasting on myth and magic from the court that lay across the bridge of dreams in Heian-kyo.

Kaori O’Connor is an anthropologist and Honorary Senior Research Fellow at University College London. She is the 2009 recipient of the Sophie Coe prize for writing on food history.

Header image by Minechika Endo